Right from the start, running in the 20th century was a bit more structured than cycling. Measured running tracks have been available since the early years of the last century, though 400 meters was not always the standard. The first iteration of the stopwatch was invented in the mid-19th century, but it didn’t catch on until early 20th century academics monitoring factory workers needed to determine how long it took a worker to complete an assembly-line task. At that point, the stopwatch made a comeback. While measuring the productivity of workers waned by World War I, the stopwatch was here to stay.

By the early 1900s running was growing in popularity due to the premier of the modern Olympic Games, which began in 1896. This is also what led to measured and standardized running tracks being built in some large cities in Europe and America with the hopes of hosting future Olympics.

Of course, running was around long before the modern Olympic Games made its debut. It started in Ireland in the 1700s with horse racing competitions between cities. Riding horses, the Irish raced cross-country from church steeple to church steeple. By the 1800s the English changed the steeple chase from racing on horseback to racing on foot and a running boom, of sorts, began. In parts of Europe and America there were similar cross-country races for young men and boys. But there was little in the way of “training” for these events. The participants simply showed up on race day and ran as best they could.

RELATED: The Evolution of Endurance Training

Paavo Nurmi, the first to “train”

By the late 19th century there were some competitors who prepared for these events, however different it might be from what we think of as run training today. Their preparation consisted mainly of long-distance walking with very short runs mixed in. By the 1910s running was done very slowly and still included lots of walking. But change was slowly coming due to a Finnish long-distance runner who competed at distances from 800m to the marathon.

Over the course of 14 years, Paavo Nurmi ran in three Olympic Games and amassed nine gold medals. He always ran on the track carrying the newly developed stopwatch to stay on an even pace, the first to see this as important to success. His training, which was only for 6 months of the year, included two workouts daily with the first being a 15–45km walk and 10-20km runs in the afternoons, including sprints of up to 300m. As he approached the race season the walking was discontinued.

Given that it was the early 20th century his training was quite progressive and would influence many runners, mostly Europeans, throughout the 1920s and 1930s. At this time running, which included short, high-intensity sprints, was starting to replace walking as the most popular way of preparing to race.

Coach Woldemar Gerschler and sport science

By the 1930s a young German coach with a background in the science of sport began experimenting with Nurmi’s fast sprints and assigned intervals to his runners. Woldemar Gerschler was also the first to start using heart rate as a metric to determine if his athletes were running hard enough. For their faster-than-race-pace intervals he aimed for them to top out at 180 beats per minute. The other changes he made to Nurmi’s methods included doing away with walking and having his runners train year-round.

Gerschler went on to coach several Olympians and world-record holders with a method rooted in sport science that is similar to how runners train today.

Emil Zatopek’s intervals

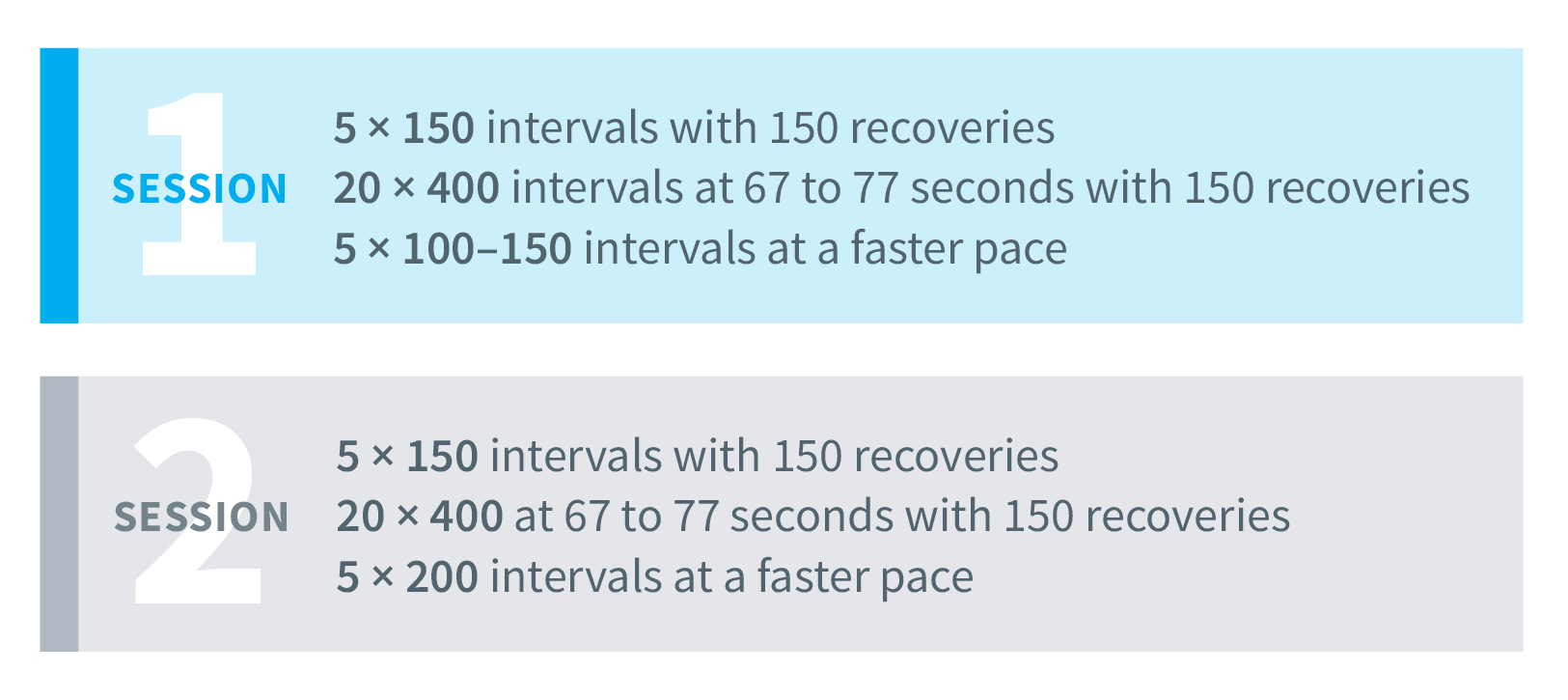

Gerschler’s methodology had a significant impact on the Czech athlete Emil Zatopek. By taking intervals to a much higher level in his training and racing with the determination of Nurmi, Zatopek went on to dominate distance running in the 1940s and 1950s. His workouts were harder than what any runner had done up until that point. For example, early in his running career, he alternated two workouts throughout each training week.

Zatopek adjusted his training over time. By the late 1940s and early 1950s he began running the 400s at 56 to 75 seconds, starting with the faster time and gradually running each subsequent interval slower. Also, in the 1950s he increased his daily training volume from about 18km (11 miles) to about 28km (17.5 miles). Feeling a need to do more, in the 1950s Zatopek began to train twice daily.

With a sense of aging and an increase in competition, he began running up to 50 × 400m intervals in a single-track session, with one workout covering about 30km (19 miles). In the week before an important race he would cut back his daily volume and run the intervals faster.

Zatopek’s impact on the sport of running was undoubtedly greater than that of any of his predecessors. On a personal note, in the mid-1960s I was running Zatopek intervals with my college track team every day. We dreaded the effort, which I deemed “intervals ’til you puke.”

Coach Mihaly Igloi and 100-mile weeks

In the 1950s another European coach came on the scene who made some significant changes to what Zatopek was doing and had an impact of training for several years. Mihaly Igloi had been a decent Olympian representing Hungary in the 1930s and specializing in the 1500m. While his training methodology also relied heavily on intervals, albeit somewhat slower than his famous predecessor’s, he also believed his distance runners should do 100-mile training weeks to build aerobic fitness. We’ll see this again 10 years later.

Following the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, Igloi decided not to return to Hungary as the country, during his absence, rebelled against the Soviet Union’s domination and lost its sovereignty. He took up residence in California where he continued to coach and worked with world-class athletes such as Jim Beatty (1500/mile) and Bob Schul (5000m). They ran 100-mile weeks and also did Zatopek’s interval sessions.

Coach Arthur Lydiard, who brought it all together

In the 1960s a New Zealander came on the scene and would go on to have perhaps the greatest historical impact on the sport. Runner’s World magazine named Arthur Lydiard “The Best Running Coach of All-Time.” He was the first to periodize the training season by introducing the concepts of a base period and a peaking routine before major races.

While he coached endurance runners at all the Olympic distances, from 800m to marathon, he required all of them to put in several 100-mile weeks in the base period, perhaps borrowed from Igloi, before starting a period of hill work followed by interval training. When intervals were employed, he preferred that his athletes not time them but rather run them based on “feel.” His concern here was that when fatigued, times will be relatively slow and could weaken the athlete’s confidence. He also believed that 6 to 8 weeks of high-intensity training was enough to produce the desired results without the threat of overtraining.

RELATED: Endurance Performance Testing and Monitoring—Past, Present, and Future

Prior to Lydiard, endurance run training was based primarily on either volume (before 1920s) or high intensity (1920-1960). Lydiard was among the first to combine the two determiners of training. His general methodology has remained much the way modern runners train. While there have been some deviations from this over the years—more long, slow running in the 1970s and 1980s, and a greater focus on intervals in the 1990s and 2000s—how we have trained runners has not seen significant change.

Note that not all top endurance athletes and coaches of the 20th century followed the training methodologies described above. Many modified their predecessors’ preparation practices. A good example of this is Roger Bannister’s coach, Franz Stampfl. In the early 1950s the Austrian born-and-raised coach had Bannister run intervals, especially 400s, at a faster pace than others had done but with far fewer repetitions. There were other coaches and athletes in both cycling and running who experimented throughout the 20th century and beyond, but seldom experienced the success that those described above achieved.