Throughout most of the 20th century, Europe was a dominant force in cycling, as evidenced by renown riders such as Thorvald Ellegaard, Marie Marvingt, Major Taylor (the lone non-European, an American), Henri Pélissier, Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, Jacques Anquetil, and Raymond Poulidor. From 1900 through the 1970s, these cyclists trained in much the same way.

RELATED: The Evolution of Endurance Training

Eddy Merckx’s training methodology

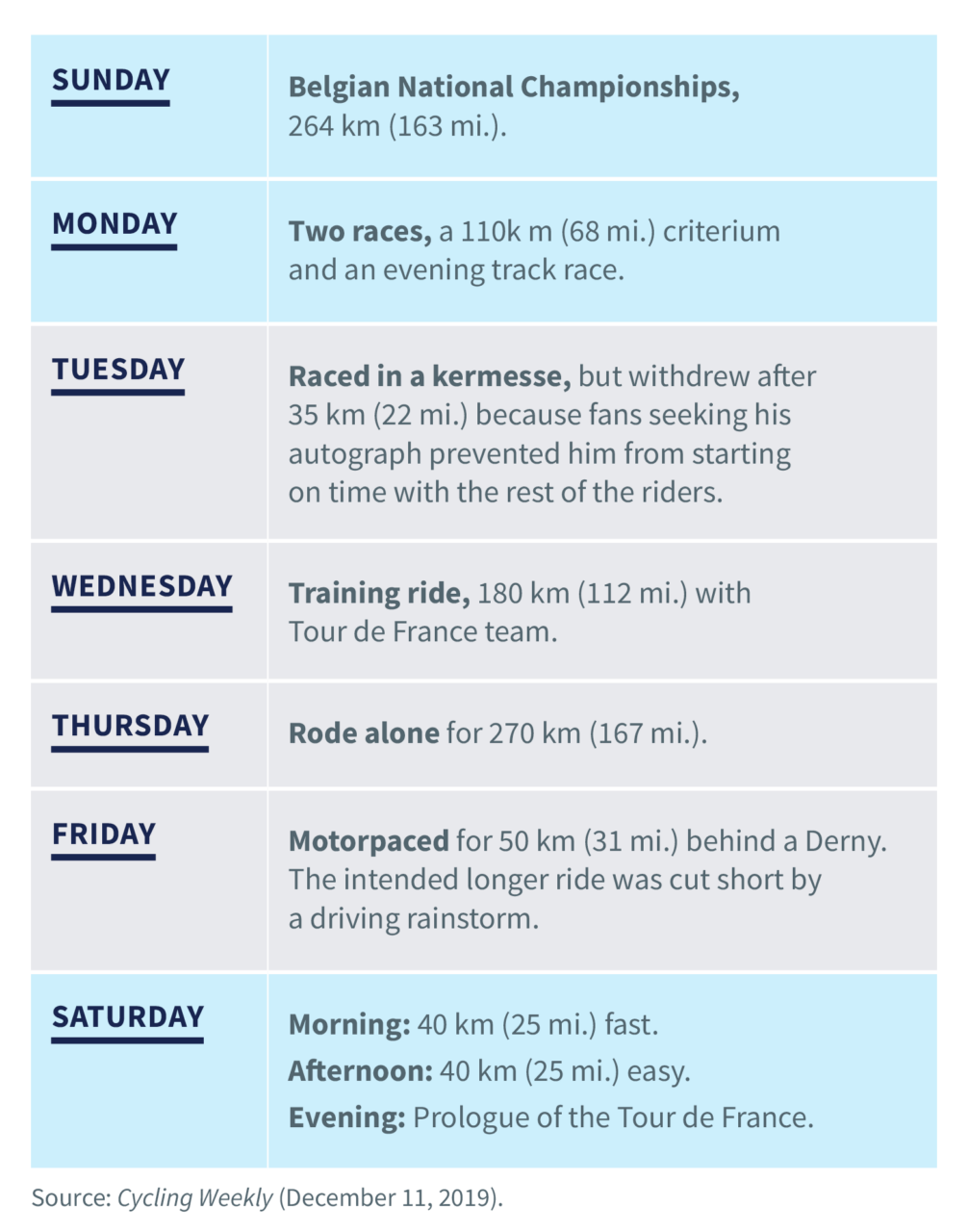

The best known, and arguably the most successful cyclist of all time, Eddy Merckx, trained with a method that wasn’t too different from what Gino Bartali had done 40 years prior. He rode many kilometers weekly and raced frequently. When asked how to train to become a professional bike racer Merckx famously replied, “Ride lots.” That pretty much summed it up. This summary of his training diary reveals the details of how he rode lots in the week before his first Tour de France in 1969:

Merckx’s total volume over this week was more than 989 kilometers (613 miles). It also included five races, culminating in his first stage in the Tour de France. Racing right up to the week of the Tour was not unusual for him. In the 1970s, he averaged 180–190 days of racing per year.

One of Merckx’s coaches during this same period, Dr. Marco Pierfederici, directed his cyclists to ride several hours each day at a low intensity, emphasizing that this is necessary for high performance: “This is what road racing is all about. Interval training will not prepare you for it.” He was quick to add that the “best training for…racing is racing.”

Dr. Pierfederici went on to suggest that weight training is not helpful, and even harmful to athletes: “Very simply, the training that a competitive cyclist should do is based on riding a bicycle. Once the season is over, there is another thing the cyclist should do—and that is to ride a bicycle. When the cyclist doesn’t know what else to do, he should do a third thing—ride a bicycle.” [1]

Eddie B and American racing

In the U.S. the high-mileage, frequent racing paradigm began to change in the 1970s and 1980s as Coach Eddie Borysewicz (better known as Eddie B) and professional rider Greg LeMond promoted a periodized and more nuanced training methodology that had been created and refined for sports by Eastern Bloc countries through most of the 20th century. The American version was developed by Coach Borysewicz, a cyclist and, eventually, a coach trained at the Polish Academy of Physical Education. He was hired by the U.S. Cycling Federation in 1977 to be the head coach of the national team.

His periodization methodology was based on three basic training periods, each with a unique purpose: transition, general preparation, and racing. LeMond, a three-time Tour de France winner (1986, 1989, 1990), who was coached for a while by Borysewicz, didn’t agree with Eddie B on everything. However, their training methodologies are described in their respective books—Borysewicz’s Bicycle Road Racing (1985) and Greg LeMond’s Complete Book of Bicycling (1988)—revealing plenty of overlap.

Let’s start with Borysewicz. Here’s an overview of his annual, periodized training methodology.

Transition period (Oct. 15–Nov. 30)

Ride easy 3 to 4 times each week. Additionally, use a bike for transportation whenever possible. There is no weight training until the last two weeks of the period (mid-November), at which point the effort is quite light and sessions are twice weekly. Otherwise, the athlete is encouraged to rest a lot and have fun. Borysewicz encouraged riders to participate in other sports (excluding running) just for fun, even suggesting “I don’t mind if you go disco dancing.”

He was also a stickler for nutrition, a topic that got little promotion from former European coaches. He directed his athletes to eat fresh, raw fruits; vegetables, especially salads; and a variety of lean animal meats, preferably cooked rare. In terms of macronutrients, he advocated for the athlete’s daily food intake to be roughly 60% carbohydrate, 25% fat, and 15% protein.

General preparation period (Dec. 1–Apr. 15)

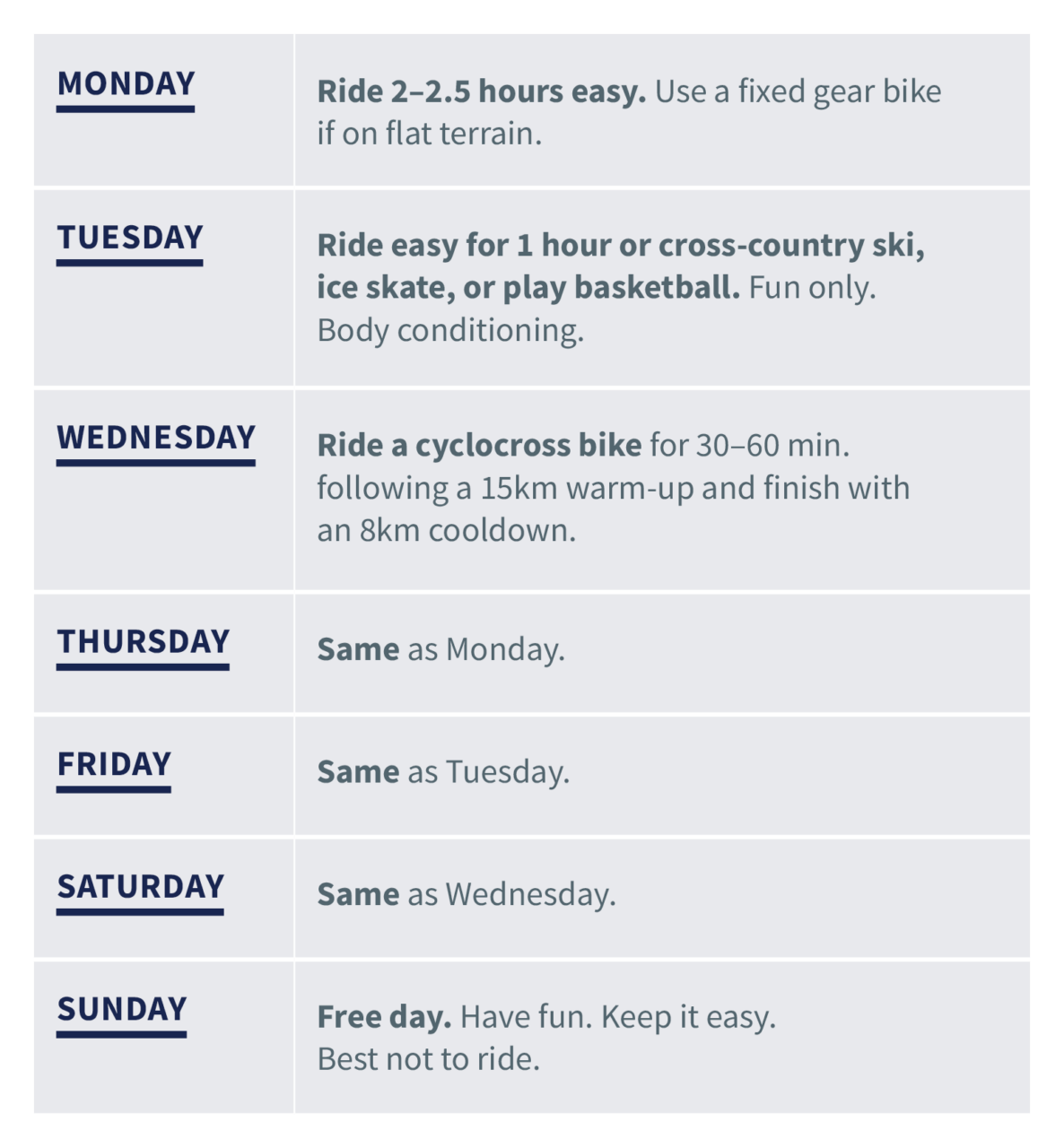

Here he directed his new American riders to divide this period into three sub-periods: December 1-January 15 was devoted to body conditioning—weight training. The weekly routine is illustrated below.

Notice the emphasis on cross-training twice a week. That’s a big change from Dr. Pierfederici’s ride every chance you get, even in the off season. American cycling programs obviously saw things differently. Had LeMond and other U.S. cyclists not performed as well as they did in the 1980s Europeans would likely have continued their “ride and race lots” methodology.

Borysewicz’s 1980s training routine changed a bit every season in mid-January, March, and April, with a reduction in weight training and the introduction of more bike-specific training. In the last four weeks of the general prep period, intervals were added. Note that this marks the onset of high-intensity training—mostly long sprints, short time trials, descending-duration intervals, motor-paced intervals, climbing intervals, group intervals, and attacking on hills. Heart rate was used as a gauge of exertion.

The general preparation period diet also continued to be an important component of training as he encouraged riders to eat 4 to 6 meals daily of the same types of foods as described in the rest period.

Racing season (Apr. 15–Oct. 15)

In this period the athlete is assumed to be racing on weekends, but usually just one race. The other important intensity day is Thursday. On this day speed and power are emphasized along with specific training for the rider’s primary type of event—road race, criterium, time trial, or stage race. During this six-month race season, the athlete is focused on producing two peak performance periods with at least two months between them. During the recovery period between these peaks the rider will train somewhat less, rest, and do only one-day races for at least a month. Then specific race preparation begins again for the second peak of the season.

The focus of workouts in the final weeks before one of the two peak races is on the rider’s weaknesses: speed (sprinting), power (climbing), and endurance (long road races). Borysewicz provided details on how to bolster these weaknesses to become a better racer in the final weeks before each of the two peak races, and he also described how to effectively taper in order to come into peak form.

As you can tell from Merckx’s training diary above, these were not common ways of race preparation in Europe prior to the 1980s. Borysewicz’s training methodology marked a real departure from how European teams trained. The only thing missing was evidence that it worked—race results. Those would mostly come from Greg LeMond.

RELATED: Fast Talk Episode 163—Training Principles from the 1980s Are (Still) All You Need

LeMond’s influence on bicycle training

In 1980 Greg LeMond joined the Renault team and made the decision to be coached by Frenchman Cyrille Guimard, who was arguably the most respected European coach of the 1970s and 1980s, having trained Bernard Hinault and others to world-class levels. When LeMond’s book on training was published eight years later, his description of how he trained remained largely aligned with what he had learned from Coach Borysewicz. What he seemed to learn from Guimard was how to race.

In addition to generally following Borysewicz’s periodized training methodology, LeMond brought a strategic approach to bike training and racing that differed from the widely accepted European methodology of riding and racing “lots.” Prior to LeMond, European riders raced frequently, as epitomized in Merckx’s training routine. LeMond focused his season on the Tour de France and used a limited number of additional races as springboards to get to the podium in Paris. Consequently, he raced far less than most of his elite European predecessors.

In fairness, there was a subtle change taking place in how racing was viewed by some of his top European counterparts. For example, Frenchmen Laurent Fignon and Bernard Hinault, arguably the two most prominent European riders of the 1980s, were also starting to focus their training on the Tour rather than on a high volume of racing.

All three riders, LeMond, Fignon, and Hinault, rose to great success in the 1980s, with eight Tour de France victories between them, which undoubtedly led others to adopt this new approach to training and racing. By the 1990s, periodized training was further evolving with different emphases on duration and intensity relative to a seasonal training plan, but still similar to what Eddie B laid out in the decades prior. (My own book The Cyclist’s Training Bible demonstrates this trend, originally published in the mid-1990s.)

By the early 2000s, training for cycling was beginning to look more like training for other endurance sports, such as running. Power was emerging as the dominant way to measure intensity, fitness, and race readiness.

Resources

- Time tested, old school early season training advice [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.wielercafe.com/2010/03/i-just-love-article-below.html