Quick, name two things that hit their peak in the 1980s. Yes, mullets were one. But think cycling and physiology. What about training principles? How much has changed since the days of Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond?

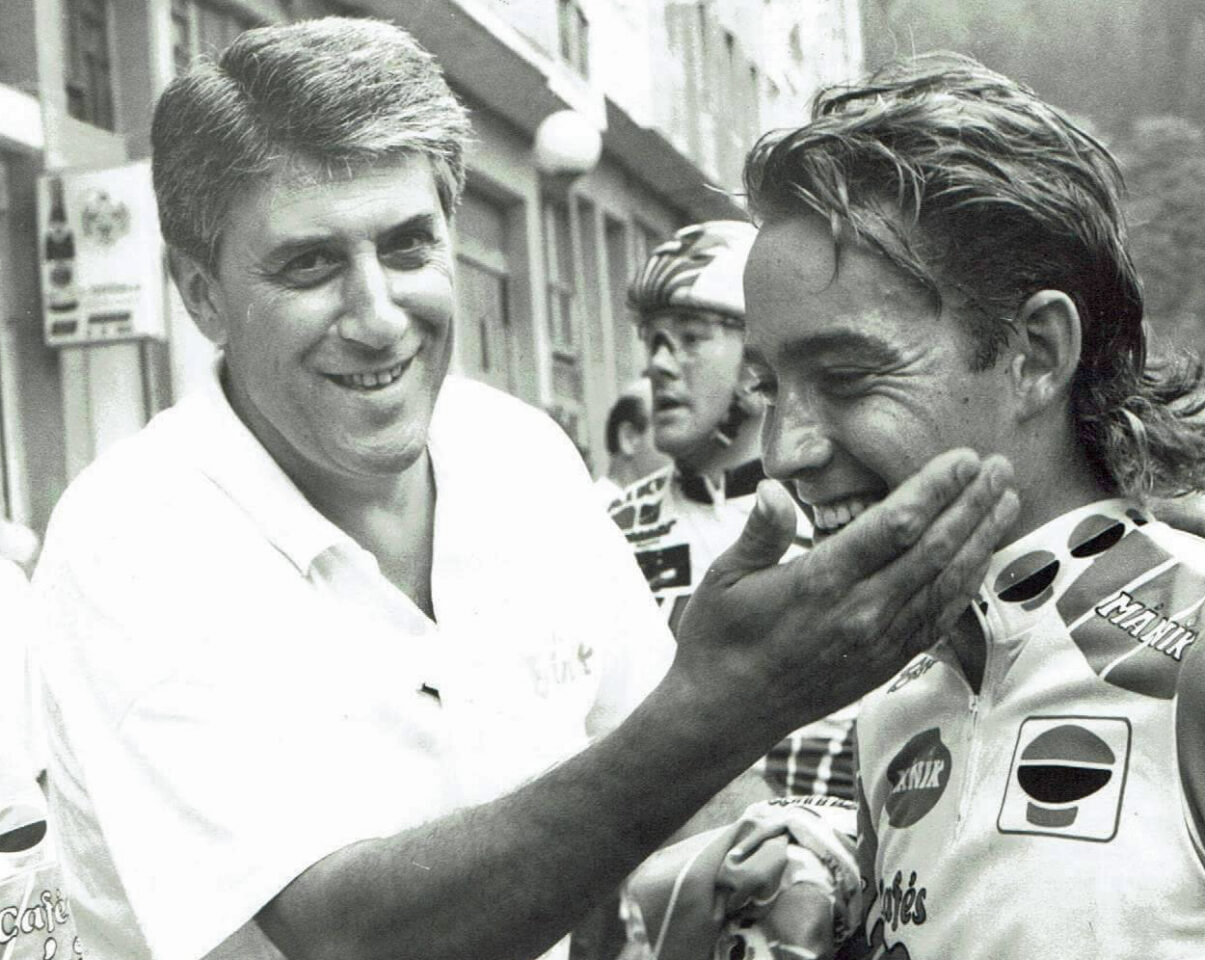

Today, with the help of longtime coach Jeff Winkler, who, yes, once raced as a pro in the ‘80s with a mullet, we discuss what has and has not changed since the 1980s, focusing on the principles of physiology. Are they fundamentally sound and equally effective as the principles by which cyclists train today?

Jeff is what you might call an “old-school” coach; he believes, in large part, that since the 1980s when he was training with Eddy B. and the U.S. National Team, training hasn’t really changed much—it’s just that we can now measure things more than ever before.

So we’ll take a close look at the science and research, the equipment, the tools and software used for analysis, then and now. Which decade wins? Stay tuned.

As a bonus, we may also discuss our favorite euphemisms for the mullet… what did you call yours? Maybe it was “The Achy Breaky Big Mistakey” or “The Ape Drape”? How about “The Beaver Paddle” or “The El Camino Headrest”? Perhaps you’ve always been a fan of our friends up north, calling yours “The Canadian Passport”?

In any case, pull out those old photos of you with your hockey hair, it’s time to go way back to the ‘80s… let’s make you fast.

Episode Transcript

Chris Case 00:12

Hey everyone, welcome to Fast Talk your source for the science of endurance performance. I’m your host, Chris Case.

Introduction to Cycling and Physiology Since the 1980s

Chris Case 00:18

Quick. Name two things that hit their peak in the 1980s. Yes, mullets, were one of them, but we’re thinking, cycling and physiology here. What about training principles? How much has changed since the days of Bernardino and Greg LeMond? Well today with the help of longtime coach Jeff Winkler, who yes once raced as a pro in the 80s with a beautiful mullet, we discuss what has and has not changed since the 80s, focusing on the principles of physiology, are they fundamentally sound and equally effective as the principles by which cyclists train today? Jeff is what you might call an old-school coach, he believes in large part that since the 80s when he was training with Eddie B and the US national team training hasn’t really changed all that much, it’s just that we can now measure things more than ever before. So today, we’ll take a close look at the science and research, the equipment, the tools and software used for analysis, then, and now. Which decade wins? Stay tuned. As a bonus, we may also discuss our favorite euphemisms for the mullets, what did you call yours? Maybe it was the achy breaky big mistake? Or the atri? How about the beaver paddle or the El Camino headrest? Perhaps you’ve always been a fan of our friends up north, calling yours the Canadian passport. In any case, pull out those old photos of you with your beautiful flowing hockey here, it’s time to go way back to the 1980s. Let’s make you fast.

Ryan Kohler 02:00

Hey, Coach Ryan here. It’s spring for most of us, which means more volume and more intensity. This is a great time to win an INSCYD fitness test. INSCYD is a lab-grade fitness test you can do wherever you are without having to visit a lab. INSCYD lets you take a detailed look at your own fitness. You’ll discover your VO2 max, training zones, anaerobic threshold, fat Max, carb max, and more. Book your test at fasttalklabs.com/INSCYD.

Chris Case 02:26

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Fast Talk. We’ve got an very interesting conversation in store today. It stems from a conversation I had with our main guest today Jeff Winkler, Welcome to Fast Talk, Jeff.

Jeff Winkler 02:44

Thank you. Happy to be here.

Chris Case 02:46

Yeah. So, Jeff and I were on the Panache ride. It’s a local ride from Boulder, not sponsored by, but just based out of the Panache company’s headquarters here in Boulder, and we were riding along talking about Fast Talk and coaching and topics, and one of the things Jeff mentioned was this idea that you know, training principles really haven’t changed all that much since the 80s. I’m paraphrasing, we’re gonna get into this, we’re gonna debate it a little bit, but mostly discuss it. And here we are, gosh, it feels like two years later with the way the world has worked in recent times, and it’s great to finally get you on the program. First of all, it’s great that I guess I should apologize it’s taken this long, Jeff, but glad you’re here and look forward to hearing where this conversation goes.

Jeff Winkler 03:44

Well, thank you. I’m excited to be here. I think it’ll be a fun one.

Chris Case 03:47

Your background, you raced in the 1980s. You trained with Eddie B, the famous Eddie B, rode for his teams back then and since then have gone on to coach a multitude of teams, athletes of different ability levels from the collegiate level to the elite level. Give us a little background.

Jeff Winkler Cycling Background

Jeff Winkler 04:09

Yeah, the Cliff Notes is I started in 1986, I was a senior in high school. I kind of I was swimming a little bit in high school, and then a friend of mine from swim team had talked about doing this ride and it kind of got me going and so I ended up purchasing a bike and then kind of doing my own thing. I ended up never riding with that guy which is kind of funny but ended up connecting to the local community racing as a junior my last year as a junior so 18 years old, and then raced in college, then ended up racing at the elite level and spending time in Europe and racing before stopping and coming back to school, and then I ended up coaching the University of California Santa Diego in the early 90s, and then in that interim, I’ve coached individuals and clubs and teams, up until once I moved to Boulder and then coached CU for six years here coaching their road and their mountain biking cross teams. And then now I’m a full, I mean, since I’ve been in Boulder, I’m a full-time coach, coaching athletes at all levels.

Chris Case 05:26

I know that this, as we tried to understand where we wanted to take this conversation, we thought, oh, it’d be awesome to have this debate. Oh, you don’t need to train any differently than you did in the 1980s. Oh, you do need to train things have changed so much. I don’t think we can necessarily take it there, we don’t necessarily want to take it there. So, today’s more going to be about there’s going to be some opinion here, it’s going to be a broad discussion about principles that existed, principles that have changed, so it’s gonna be a very broad discussion about some big topics in training and sports science. What do you want to lay down some ground rules here, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 06:05

Chris came to me with this idea after he talked with you, Jeff, I thought it was a really cool idea. As we got ready to start preparing for this one and putting together an outline, I realized to do this scientifically, to be able to say, you know, here’s what the research is showing, we would literally have to research everything that has been discovered, advanced, whatever you want to call it since the 1980s.

Chris Case 06:34

Yeah, a good forty years.

Trevor Connor 06:35

Find research showing whether those changes have actually produced improvements in athletes. So, a couple of days ago, I talked to Chris, I’m like, I would have to read four or five hundred studies for this episode. So that, unfortunately, wasn’t doable. So, I apologize to our listeners. This is going to be a little more our opinion. I’m sure we’ll bring in some research, we’ll talk about the changes in the science. Great to have you with us, Jeff, because I think ultimately, what we’re going to talk a lot about is coaching experience. So, you’re going to get a bit of an opinion, you’re going to get a bit of experience, just understand that, unfortunately, going through 500 studies in three days.

Chris Case 07:20

I can’t believe you didn’t do that I’m really disappointed in you.

Jeff Winkler 07:24

That wouldn’t be the complete answer either.

Chris Case 07:26

Yeah, true.

Trevor Connor 07:27

Probably not.

Jeff Winkler 07:28

How science has moved over the last 40 years, but maybe not wheels on the road.

Chris Case 07:35

So, Jeff, you live this. What was your training like in the 1980s? Take us back in the way back machine if you would?

Training in the 1980s

Jeff Winkler 07:43

Yeah, I’m going to start with a little disclaimer and just say that my experience may not be exactly the same as everybody else who was racing at the time. In fact, I’ve talked with my contemporaries who raced a little bit before me, and I got the sense from them that they were winging it kind of in the old school model, that we’ve kind of come to know, all LSP and that kind of thing. So, but for me, so I started as a junior, I was living in Bakersfield, California, which is a bit of a backwater, and certainly, there was no great cycling community like a Boulder. And so, I kind of had to take it upon myself to figure it out once I got serious. Certainly, I found a community and I rode with them, and certainly, you know, maybe something that was a little more common in the 80s and 90s was that a lot of your development came from your community, like those who are further along the path than you would pass down knowledge. But you know, the 80s was a weird time, I mean, if you think about the history of US cycling, the generation of US pros were active. So, there was nobody to be the coach, right? There was no coaching community. Basically, the only coach at the time of note was Eddie B, Eddie Borysewicz, and he was the national coach in the mid and late 80s, and then it became Chris Carmichael as we went into the 90s. I rode with Chris on the national team a couple years after I started.

Relying on Books As Training Guides

Jeff Winkler 09:29

But so, you know, for me, it was books, and you know, unlike now where you just have all kinds of information, there just weren’t that many sources. I did a little trying to dig them up, and I did get rid of Eddie’s book, but Eddie’s book was probably the first one I saw. I mean, it looks like a textbook, you know, it’s a big book. Then Greg LeMond published a book in the mid-80s, so did Bernardino, and I also had a book that was by an exercise physiologist from the Netherlands, and that actually was a pretty technical book a lot of lactate data and, you know, analyzing different athletes at different levels of the sport. And so, I kind of just relied on those as training manuals, if you will, and they did have, like Greg’s book especially had like, a progression is like, okay, you know, you’re 15-16 or junior, and they didn’t have U23, but, you know, and then an established Pro, and they had annual kind of guidance that would carry you along. I adopted that, you know, and I read them all, but I, you know, I kind of integrated it all, and was self-trained, until I rode with Eddie. And then, and, or, and, or the national team, and there was that, but even then, there was no, like, strong coaching influence, there was no one who was a coach in my community. And I had no contact with a cycling coach until Eddie.

Improvements in Cycling Since the 80s

Trevor Connor 11:08

So, we’re definitely getting ahead, but I agree completely. So, I made a list of some of the things that I think have improved since the 80s and some of the things that have not improved. Big on my list of things that have improved is this filtering down of good training practices. Now, because of the internet, because of a whole variety of means, it is possible to get good information, even the research it just in the last few years, you’ve seen a change in the research, where instead of just being a, let’s put people in a lab and do a six-week study, which gives you some information, but not enough, they’re now able to dive into the data of athletes that have been highly successful and see how they’ve been training for the last few years and pull out trends and things that actually seem to make a difference. I think in the 80s, as you said, it was probably a trying to find any little scrap of information you could, it generally came down to you’re out on the group ride, or you’re training with a team and you’re asking people, and unfortunately, you’re just as likely to get the advice of don’t sleep with plants, as you are, here’s some good training practice, and really, you had no way of knowing what was effective and what wasn’t.

Jeff Winkler 12:29

Sure. Yeah, definitely the democratization, if you will, to use the common term of that information has made it possible like it’s raised the baseline, I think, would be fair to say.

Differentiating Between Principles and Practice

Trevor Connor 12:42

So, I think an important distinction we need to make right now because this is going to be very important to the rest of the episode, and this question of having things changed since the 80s, is to differentiate between principles and practice. I will say we were originally thinking to do in this episode, as a debate, you are going to take one side, I was going to take the other side. In our conversations back and forth in email, we’re like, we kind of agree on all this, who’s gonna have to try to pretend they agree with something they don’t. When we’re talking about principles, we’re talking about bigger picture things like the principles of physiology, the one that we mention a lot there several, but one of them is the whole overload principle. There’s also you could go into some of the principles of how you overall execute, like should you periodize? Practice is much more the, how do you execute your training to maximize those principles? So, that would be things like talking about Tabatas versus threshold work, talking about recovery lengths, talking about zones by power and heart rate, those are all the practice things. I think we’re all on the same page here of saying the principles really haven’t changed since the 80s, particularly principles of physiology, because our physiology hasn’t changed. When we talk about the practice there, there are things that are didn’t even exist in the 80s that are now quite prevalent. One example basically being power meters. Yeah, they did exist in the 80s, but nobody had one.

Chris Case 14:20

Would you be able to put words or descriptions or names to the principles that existed back then?

Principles That Existed in the 80s

Jeff Winkler 14:27

Sure. If I was to, like, draw it at a very high level, I would say that maybe everything was centered around function, right? It’s like what was the fitness aspect that you needed to develop? And so you know, which is really no different than today, right? It’s like you have to work on sprints, you need to work on short intervals, you need to work on long intervals, and you need to work on endurance, you know, so the training plan was organized in that way that you focused on each of those things in a progressive manner. You know, he was periodized, it looked like the things we do today, where you would have, I don’t know what the words of like microcycle and macrocycle and mesocycle have kind of fallen out of popularity, but those were front and center. So, you had annual periodization, you had essentially the equivalent of today, like with build and bass and, you know, peak, all of those things existed. So, that what it looked like, and so you would have your plan, I would lay it out on my own, mostly, and then I would, you know, endeavor to adhere to it, modified as necessary. That was training, that was what training looked like. But I don’t know if it’s true today, certainly, maybe not at the amateur level, but we also there was only a certain part of the year that you trained, then it was racing.

Chris Case 16:00

Hmm.

Jeff Winkler 16:00

And so there was a ton of pressure, most of the pressure was on preparation for the season, but then you raced so many times that it was really race and recover. That’s like a difference, I think, as I said, it’s what I see with some of my athletes now, I’d say that you know, I didn’t have to train much after April.

Chris Case 16:19

I want to maybe take us down a slight tangent here, Eddie B, is this somewhat iconic figure, somewhat controversial figure, Jeff, I wonder, in your experience, did he bring a lot of practices and principles perhaps, or one or the other to the United States that hadn’t really existed in a formal way beforehand for him?

Eddie B and His Influence on US Cycling

Jeff Winkler 16:48

Yeah, I think you have to give him credit for that. He may not have been like the most expert, you know, coach, there were certainly some controversial things at the national level under his tenure, but I think he brought the status, I mean, he brought the information that was kind of mainstream in Europe at the time to the US, and that was really the first time that it arrived. We were probably really uninformed until he arrived, certainly like the national level that brought some organization. I think team tactics probably we’re not, you just didn’t have the guidance, it was the complete absence of guidance, you know, you probably had two riders that were international pros in the early 80s, but then the whole generation of 7-Eleven kind of came up with Eddie’s arrival, not that he made it happen necessarily, but he certainly coexisted with the birth of modern US cycling.

Chris Case 17:54

Did he set the United States and the community of cycling here on the right trajectory? Do you think, in your opinion?

Jeff Winkler 18:04

You know, A/B testing is always a challenge. Could someone have done it better? Yeah, sure. I mean, if you had maybe some of the most notable, like Gaymard’s and Paul Coakley’s, and these guys who are in Europe that were running sports programs, or national teams or teams, if they had come over, maybe they would have been more sophisticated than Eddie was, but he brought I mean you can almost parallel this for a coach like when you take an athlete who has never been coached, or never had a plan and say, well, you’re gonna get better just by having a plan and a system, right? And so, Eddie brought a system, and that system was good enough for progress.

Trevor Connor 18:54

Lennard Zinn, the world’s leading expert on bike maintenance and repair started his career as a professional cyclist in the 70s and has seen many changes in how riders train since then. This is what Lennard had to say.

Lennard Zinn: Changes in How Riders Train Since the 70s

Lennard Zinn 19:05

I think is radically different. I think we all believed at the time that you pretty much hammer all the time, like rides we do at the athletic training center, you know, on a windy day, we’d go out and we just, it soon split up into these really hard echelons where you’re literally trying to split the group apart and echelons, or, you know, you go up North Cheyenne Cañon, and it’s 20% grade, and you’re just trying to beat everybody every ride.

Chris Case 19:44

Every ride.

Lennard Zinn 19:44

Always competitive.

Distinction Between Health and Fitness

Chris Case 19:47

No rest.

Lennard Zinn 19:48

Yeah, well, yeah. So, now I think the understanding of the distinction between health and fitness, I’d say was something we never even thought about back then. And, but to have this understanding that you really need to have the vast majority of the training you do be very easy, and build a base and, create this big foundation of health, and then you can add the speed on to the top of that, but it would be a very small percentage of what you do is where you’re really hammering yourself, and when you do you really go much harder because you’re not doing that every single day.

Chris Case 20:41

Right. Right.

Lennard Zinn 20:41

And so yeah, I think it’s a huge difference. I do think that back then there were guys who had the sense of that, who just were able to listen to their body and did and, but most people had no clue, and we’re always trying to impress their riding buddies or the coaches or whatever, on every single ride. And, and the guys who had the ability to be last on the training ride, those were the guys who ended up staying in the sport longer.

Trevor Connor 21:21

Yep.

Lennard Zinn 21:22

Being good longer, all that sort of thing, but they were few and far between.

Trevor Connor 21:28

Though, I will say one thing that hasn’t changed there is whenever my athletes say, “Oh, I’m going on this group ride, but it’s an easy non-competitive group ride.” I always tell them, that’s the unicorn they don’t exist.

Chris Case 21:41

Right. Right. I’m curious also about how nutrition may or may not have changed. What did you eat at the Olympic Training Center In 1980? Versus what do you think they’re eating down there now?

Changes in Nutrition

Lennard Zinn 21:57

I don’t know what they’re eating now. There’s more sense of food quality now. We didn’t have such a sense of food quality. I mean, I tended to be much more like, you know, when I was in the 1970s, I was into organic food. Nobody even heard of organic food back then.

Chris Case 22:14

You were a unicorn back then.

Lennard Zinn 22:15

Yes, I was the unicorn. I was a vegetarian, when I was at Olympic Training Center, I was vegetarian and the coach, Eddie Borysewicz, Eddie B, would say, “must eat Polish sausage.” And he berated me constantly about, about being a vegetarian, and I was pretty stupid about it. I’m pretty sure that, that I left lots of results on the table because of like, for instance, I remember racing the Tour of Ireland and I’d say, “Oh, yeah, I’m a vegetarian.” It’s like, well, basically, I got to eat potatoes every single, every single day and every morning, I got beat soda bread with jam on it, you know, with the marmalade on it, and that was what I raced on, and, and I had no sense of really balance and all that, but the quality overall food quality at the Olympic Training Center back then was pretty low. I think, you know, it was not surprising, like to get a tray full of green beans that were like those really there are ones that have gray and totally like poured out again or something.

Chris Case 22:58

It sounds like you were in prison actually. Prison food.

Lennard Zinn 23:37

Yeah. Yeah, it was.

Chris Case 23:39

So, it’s also changed pretty radically.

Lennard Zinn 23:42

Yeah, yeah.

Lennard Zinn 23:43

I mean, I did have lunch there, I don’t know maybe 10 or 15 years ago, and I was like, “Wow, this is upscale this is good food and lots of really good choices.” Yeah.

Chris Case 23:43

Yeah.

Chris Case 23:56

Infrastructure, there was no coaching in the United States in a formal way, in a ubiquitous way back then, and so like you did, a lot of people were learning by reading books from elsewhere are learning books from big-name pros, and piecing things together. Flash forward 40 years, and now, you could say there’s so much information, there’s a saturation of the marketplace with content and coaches that people are confused, maybe overwhelmed, perhaps slightly intimidated by the vast amount of things, and the contradictory messages they’re hearing.

Changes in the Infrastructure of Cycling

Jeff Winkler 24:43

Definitely, I think that’s the challenge. The transformation has gone from a challenge of a scarcity of information to an overload of information, and perhaps conflicting because you also have to think that the late 80s, early 90s period is pr-internet. So, there was no way to even access remote information, which is why you were relying on books, you know? So, I mean, how would you even learn about the existence of a book, you know, where it’s just the Internet has become such a normal part of how we do things now, it seems hard to imagine like, how did you even find out things? But now you do have the sort of related problem, which is, there is easy access both as a consumer and as a producer, and so then you have a lot of information you have to work through to find the sort of gold.

Chris Case 25:40

So, going back to where we were a bit talking about the 80s, some of the things that, you know, I’m gonna play novice here, periodization seems like a huge principle that may not have been given birth to in the 1980s but was popularized, at least in the United States during that time, and I’ve got to think that that was a fundamental shift in the way that people trained.

Periodization Principle

Jeff Winkler 26:12

Yeah, I’m gonna have to say, for me, I never knew a time pre-periodization. So, my exposure to the sport and training preparation, that was the starting point. So, I think you could probably say, periodization was more simplistic before my time, but probably still existed in some form. It would just, it might have been as simple as, you know, in season out of season kind of thing, and, you know, you might have just started, okay, you just get on your bike on January one, and you, you know, you ride two hours a day, and then in February, you ride three hours a day, and you know, that would have been a little bit before my time. Then the races would start and then the races would improve your form through doing the activity that you’re actually training for. If you read some of the books published by the older pros, like Sean Kelly has a book and you read his pathway, which was before mine. So, he would have come up in the 70s. It was centered around racing, and in fact, some of his directors basically, that to keep the guys off the couch would just make them race more, right? So, make sure that there was like the true offseason, but then it was like, okay, no, January one you’re racing, and you know, you’re not going to get four weeks on the couch. So, we’re going to go to this other race right after this one finishes, and I think that was not periodization as we know of it today.

Chris Case 27:57

That sounds like there were training races, and there were races, and there wasn’t such a thing as training and it’s very simple terms.

Jeff Winkler 28:06

I was gonna say for me, the training season was like January to April 15th, and then it was like, okay, let’s race, recover, race, recover. If you have a big break, or you want to induce a peak at some particular time in the season, you might do something a little bit around that, but otherwise, racing took you to the next level, from your training in the preseason.

Physiological Pathways and Adaptations

Trevor Connor 28:30

The other thing I’ll point out that is becomes more sophisticated, and ultimately impacted how you periodize, interested in what your thoughts are on this. But certainly, when I was starting out, and I wasn’t actually doing any racing in the 80s, so I’m really my sort of my experience was the early 90s, but even then, they tended to talk about in terms of central and peripheral factors. So, you got to train your central conditioning, which is really referring to that oxygen delivery, and then train your peripheral factors, which is at the muscle level, and the idea being long, slow training, volume trains the central, and high-intensity transit peripheral. So, in the base season, you do a whole lot of long flow, and then during the season, you do a whole bunch of intensity. It was kind of simplistic, and it was based on a lot of assumptions, not a ton of research. One of the things that I think is changed, and this is particularly in the 2000s was as they started to identify the physiological pathways that produce adaptations, they could start to see the genetic markers that do and don’t produce the sort of adaptations we see in training, it became much more sophisticated, and they realized, actually, that’s really not the case. You can’t just simply divide into the central and peripheral, it does appear that all training tends to train on different sides, and what you see now more coming out of the science is trying to maximize the ways of producing these adaptations with a good understanding of our energy systems and the ways we adapt. That was not something we had in the 80s.

Jeff Winkler 30:15

Yeah, I think you’re right. Certainly, there was no knowledge and easy access to be in a feedback loop with chemical markers and triggers for adaptation that science has enabled more recently. But I do think it was, at least for me organized, I want to use this term functionally, right? You know, you kind of looked at what are the demands of the sport, and the training was built around the demands of the sport. And so, I never was in a scenario where I only rode bass, you know, for months on end, as sort of like step one in the training process. For me, in my experience was that existed in the offseason, and that was just because you were trying to get a break from intense training. But on January one, I was in at all levels of intensity, sprints to short intervals, anaerobic systems, or aerobic systems the whole bit. And yes, there was long, steady distance, but it was really for the purpose of the endurance, and it was tuned to the length of the races that you had to do. It is simplistic, because you don’t have as many variables to target, but I think there was value and just looking at what are the demands of the events you’re trying to be successful in and train for them. So, it was a little bit more functional than systemic, you know, like the actual physiology piece in detail.

Trevor Connor 31:46

Kind of goes back to this argument of the principles haven’t changed, there were probably people back then who had a really good understanding of how to train even if there wasn’t as much science behind it, and you were one of the lucky people to be exposed to that, where there was a whole bunch of us, as we said, as you called it, there’s been a democratization of this information. Back then, I was not one of the people who was exposed to good information. So, I got a whole bunch of crazy notions that were shared with me before I finally talked to somebody who knew what they were talking about.

Chris Case 32:20

Right.

Jeff Winkler 32:21

Yeah, I think I got exposed to the crazy notions when I went to Europe more than here, and it was like, classic I mean, it was like a joke, you know, it was like the European wives tales basically, about don’t walk the day before a time trial, and you can’t have tomato sauce, because it’s acidic, and you can’t have ice cream because it’ll make you sick. I mean, there’s a guy raced with who was from Poland, who would not have cereal with cold milk, because it was cold, and it would make you sick, you know, so there was a lot of that kind of stuff.

Chris Case 32:58

I love it.

Jeff Winkler 32:58

That’s gone.

Chris Case 32:59

Give us more. Give us more, Jeff, I want more of these nuggets.

Jeff Winkler 33:03

Yeah, I’m trying to think there was some stuff in Spain that was pretty funny, because I actually got like antagonistic about it, because they would say, “Oh, no, you can’t have that,” you know, you won’t race well if you eat that. I was racing well, so I just basically was like, “Well, I’m gonna eat it and show you you’re wrong.” You know?

Chris Case 33:22

Here’s a little science experiment for you. I will prove you wrong.

Trevor Connor 33:28

Longtime New England coach, Amos Brumble, does feel a lot has changed pointing to the better decisions athletes and coaches can make with the tools we have now. Here’s what he had to say about the 80s versus now.

Amos Brumble: Cycling in the 80s vs. Now

Amos Brumble 33:40

I think the basic principles are mostly at play, and I tell people progressive overload is the most basic thing and we just have much better ways of showing that now, it makes it, you know, it’s given us a lot of different workouts, but for me, you know, when I started, you know, the only metric I had was speed. So, you know, I still continue to use it, you know, but a lot of my workouts that are not my favorite ones in terms of like how I do them are based on, you know, better information that’s available now.

Chris Case 34:21

Do you think that you are the exception to the rule and you’re just kind of an old school guy and that’s why you train the same way you used to? Or is this just a fact of physiology?

Amos Brumble 34:39

You know, I think you know, given no training advice I tend more towards being like a kind of like a sprinter. You know, believe it or not, I actually don’t do any of those workouts anymore. I actually use Xert quite often, and I actually put those workouts on a Garmin IQ app that runs while I do the ride, and I’m just hitting the numbers, believe it or not.

Chris Case 35:09

Yeah, well, that sounds somewhat modern and sophisticated to be using those tools.

Amos Brumble 35:14

Yeah, there’s a difference between, like the things that I really enjoy doing, and I do think they have benefit, and maybe what I’m actively doing, or actively recommending that other people do in terms of coaching. And, I mean, I do think training has changed a lot, and I think that shows up when you look at how quickly a rider can develop a lot of power, you know, in a modern, you know, like coaching situation compared to what would have likely happened, you know, 20 or 30 years ago, the person, they can be coached to a much higher level in a very reduced period of time, in my opinion, and, you know, I think training has changed significantly in terms of coaching knowledge.

Trevor Connor 36:02

So, to flip this question around a little bit, picture yourself back early in your career in the 80s. What things exist now, any other training or technology or whatever, that you would say, “Boy, I wish we had had that back when I was starting?”

Differences in Technology

Amos Brumble 36:23

To tell you the truth, I was that guy that bought everything as soon as I could get it. So, my first heart rate monitor was a road gear computer, in the heart rate monitor actually had a wire that went from the chest trapped and plugged into it. So, I mean, I’ve used heart rate monitors for like a long time, didn’t know what to do with unnecessarily, but I think the power meters made the biggest difference, and I think the availability of actually having a coach, like so technology in terms of like the internet, to communicate with somebody who’s a better coach, and can help you. I mean, that’s what I would give anything for is to have a coach from today, to be able to go back in time and find me when I first started.

Chris Case 37:09

Who would you pick as your coach? Do you know?

Amos Brumble 37:14

Off the top of my head, I just have to say, Trevor.

Trevor Connor 37:17

Oh, boy.

Chris Case 37:21

I was really hoping you would say that.

Trevor Connor 37:23

If I could go back to the 80s and have one thing that I have today, it would be my bikes, because then they would be new.

Chris Case 37:29

Yeah. Right

Chris Case 37:34

Can you train like you did in the 80s and still see progress and put out great performances? And the answer is yes, but there has been, quote, unquote, progress as well, when it comes to the art of periodization.

Lack of Technology and Developing Internal Gauge

Jeff Winkler 37:51

I don’t think you can honestly take the position that the advances that have occurred over the last 20 years would have no impact. You certainly could emulate you could progress you can overload without the technology and the tools that we have today. It would seem simplistic by comparison, though, and maybe as a form of an example, is that now you can rely on a power meter to be very specific in terms of pacing intervals, and that’s linked to the underlying physiological systems and all the purpose in science that’s behind it, that you couldn’t possibly do it in the 80s, because there was no power meter. I mean, you did have heart rate, so you could use that tool in certain circumstances, but what we did, in reality, was that we achieved a similar thing because we believed at the time in this basically the power duration curve without the terms, because you knew, okay, well, there’s a maximal effort for one minute and there’s a maximal effort for two minutes and they aren’t the same from a power perspective, but from a subjective perspective they are the same, they’re maximal. So, in a way you achieved something similar you just couldn’t do the nuance that you can do today which is say, what if you want to do a submaximal effort? Then it was blunt, right? Your tools were your internal gauge, which of course is a whole other discussion is when you don’t have the tools to give you the feedback, you were forced to develop your internal gauge, your RPE, your subjective perception of the effort. I do believe people had a much better tuned, you know, this is making statement that’s very broad, and there are exceptions, but people had to tune in to the internal experience more than they have now.

Trevor Connor 40:11

But now you’ve jumped ongoing to what I was hoping to discuss at the end of this, the things that we think have improved and gotten worse, you just landed on my big item of what I think is actually gotten worse since the 80s, which is we are hit with so much data, so much information, so much analysis, we automatically assume that’s better, but I will make the counter-argument that that sometimes gets us so focused on particular numbers, fo focused on a particular graph, that we start to lose the self-awareness, the sense of self, the idea of, well, I need to know what the right intensity feels like.

Jeff Winkler 40:51

Right, right.

Trevor Connor 40:52

And I’ll give you an example. Chris, and I got an email yesterday from somebody who was quite frustrated because he was trying to execute a particular interval, and he sent a very lengthy explanation of questioning of, should this be at my FTP or my anaerobic threshold? And my response is well, it’s a range, and the fact of the matter is doing those intervals. So, let’s say your FTP is 310, your anaerobic threshold is 300. My argument is going to be one day FTP is going to be right, one day anaerobic threshold is going to be right, another day neither is going to be right. Because every day, you’re going to be a little bit different, and it’s going to move around. So, you have to know what it feels like to do the intervals, right? You can’t just say, well, here’s what a bunch of graphs tell me is the right number, so I’m going to go out and just do this number, and in the 80s, you had no choice but to really learn the right feel.

Racing to the Power Meter Instead of Effort Level

Jeff Winkler 41:55

Yeah, and you see it in that’s, that’s something you see that is just executing the interval would be one thing, but even in races and other scenarios, where it’s more race craft, your race craft suffers by not having that internal perception. I worked with an athlete years ago, who was a TT specialist, and in a particular race the power meter was reading wrong, and he raced to the power meter instead of his effort level, and it was reading high. So, he didn’t go as hard as he could, because the power feedback said, you’re at the right pace, and it’s a throwaway race because he didn’t go as hard as he could.

Chris Case 42:42

He’s lucky it wasn’t in his A race, or the National Title race or something, because he would have lost because of that.

Dependence on New Technology

Jeff Winkler 42:49

Right. And then sort of the contrary, or the flip side of that is also true is that I see on a regular basis is when people see low numbers, it gets in their head, right? They can’t it actually is self-fulfilling, and if you go back to the early days, you know, the back then whatever the you know, low tech days, you didn’t really I mean, you were like, oh, yeah, I feel good or I don’t feel good, but you didn’t have this very precise feedback that said, oh, yeah, you’re 10% off, or you’re 20% off, and it couldn’t be a feedback loop, which exists now. So, you get this negative piece of data, and then it makes you suffer more, and then you look, and you see the negative getting more negative, and then you just downward spiral. So, I think yeah, that’s the challenge is to take the advances and not have them replace the good things from, you know, the old days if you will.

Chris Case 43:49

I want to arbitrarily force a little bit of competition here between decades, the 1980s and the current decade. So, it sounds like, yeah, this is completely made up, basically but periodization has, quote, unquote, improved. So, let’s just say that the 2020 decade wins when it comes to the application of periodization, in some ways because of the tools. However, the 1980s athlete in terms of being a self-aware, athlete who can feel his way into a good performance or subjectively know, quote, unquote, know that he’s hitting the target, whatever that may be, let’s put a tick box in the 1980s for that one. So, we’re tied one to one at this point.

Trevor Connor 44:47

Nice. We got a tie. Quickly share another story of talking about that feel versus the numbers. This is a conversation I had with an athlete a few years ago, he was talking to me about, how do you break away from the feel? And he was insistent on what sort of power should I put out, to get away from the feel. I kept going, whatever powers needed to get away from the feel. But what is that power?

Chris Case 45:09

Yeah.

Trevor Connor 45:10

Like it doesn’t work that way and anybody who’s experienced breakaway artists will tell you attack, you look under your armpit to see if the field is chasing you down or not, and if there are chasing you, you have to do an assessment of your head of can I go hard enough to hold them off? And he just wasn’t getting that. So, he’s finally like, what’s the power? And I just finally kind of in frustration went, “Here’s the power, it’s whatever power it takes for you to puke your guts out in five minutes, and then keep going for another hour.”

Chris Case 45:40

Yeah.

Jeff Winkler 45:41

It’s 500 watts.

Chris Case 45:42

Yeah, sure. 500 watts.

Jeff Winkler 45:44

Yeah, yeah. I mean, it’s yeah, as you as we all know, the racecraft is what drives that its timing. What is the feel doing? You know, and that’s that, you know, and you could do the same thing 10 times, and fail nine times and succeed once.

Trevor Connor 46:01

You can attack the field at 500 watts and not get two seconds on them. There are other times in the race where you can, right away, get 30 seconds on the field never break in 300 watts.

Chris Case 46:12

Right.

Jeff Winkler 46:13

And I have another little anecdote story, which comes into like, if I had data, this probably would not have happened. It was a road race, and I was not having a great day and basically, I determined that part of the way through the race, and I told my teammates, I said, “Look, I’m not feeling it today. I’m ready to just suicide for you guys.” And at that point, it made sense for me to just I said, “Look, I’ll cover everything in the last third of the race, and you guys just hang back, nothing will get away, and you guys put in the race-winning moves at the end.” And I switched mentally, you know, from not feeling good to like, okay, now it’s my job to cover everything, and I covered everything. And then I covered a move that then rolled away, and then I was in the break and the field wasn’t coming back, and I was like, oh, well, okay, I guess I’ll just have to win this race now this is on me, I’m here.

Chris Case 47:10

Right.

Jeff Winkler 47:11

And I won the race, but all of it was from a switching mindset, not from a change in physiology, and if I had had power feedback probably in that first part of that race, or even in the break, or who knows what, I would have just said, this isn’t possible.

Chris Case 47:27

Interesting.

Jeff Winkler 47:28

Yeah.

Chris Case 47:28

Yep.

Jeff Winkler 47:29

Yep.

Chris Case 47:30

Let’s maybe move on to a specific item, the heart rate monitor, and talk about that, in the context first of the 1980s, and then we can talk about, has it improved? Has the technology advanced in any way? Are we in the same place as we were back in the 80s? So, Jeff, tell us what type of heart rate monitor were you using back in those late 80s days?

Heart Rate Monitor Today vs. in the 80s

Jeff Winkler 47:59

I think I had one of the early Polars, and, you know, wasn’t really small enough to go on your wrist. I mean, I had a wrist strap and everything, you know, but basically, we had little foam things that you would clip on it, basically, a little bit like pads on a BMX bike or something where you’d put that on the handlebar, and then you’d put the watch on there.

Jeff Winkler 48:21

But I think technologically, it was more or less on par with that make sure the accuracy was not as good as it is today. But one thing that was absent was the post-analysis piece, like there was no sort of downloading it that I recall ever doing anyway, you know, downloading it to something and then reviewing it, that wasn’t part of my use of a heart rate monitor.

Chris Case 48:21

Right. Right, yes.

Jeff Winkler 48:26

Simply in the moment that you used it.

Trevor Connor 48:53

Yeah, there was no software.

Jeff Winkler 48:55

Yeah, you viewed what was going on in the moment. And the way that I actually used it was not all the time, and probably because there was nothing to do with all the time data that the value of looking at it all the time didn’t seem to be that high. So, what I would do is periodically, I would do a particularly hard workout with it, and check whether my internal gauge was accurate. Like, I’ve been doing these interval workouts, and I feel like I’ve been going as hard as I can, does my heart rate reflect that? And that’s how I would use it and so not every workout did I do it, and I don’t remember having any real like sort of wound up feelings about using it or not using it like we might see today. It was just kind of like okay, no, probably now is a good time to make sure I’m really going that hard, and that’s what I would use it for. Never raced with it, and that was that was heart rate monitors for me so.

Chris Case 48:55

Yeah.

Chris Case 50:08

So, a complete lack of historic data, no trends could be spotted, no patterns could be seen. It may be a bit of a check on that RPE, that sense that you had inside but otherwise it was not utilized?

Jeff Winkler 50:26

Well, I mean, think about it, it’s like heart rate doesn’t change that much once you’re reasonably trained, right? Your threshold heart rate remains your threshold heart rate, more or less with discounting age. But you know, your power at heart rate, that threshold will change, but so your max heart rate and your threshold heart rate, you know, those were kind of fixed things, and so it was sort of just checking, okay, is my subjective perception of this effort in line with what my heart is doing on the day I’m looking at it, you know, and we know that changes depending on fatigue state and all those things, but I mean, I didn’t get too wrapped up about that, you know.

Trevor Connor 51:03

I have years where the just sheets of paper where I would write down the date, the length of my ride and time, the distance, the average speed, and once I finally had a heart rate monitor, my average heart rate. That was the only data you could write down and have any sort of record of, and I still remember when Polar finally came out with a heart rate monitor where you could download it and graph it, that was the most incredible thing. I think that was like 2000-2001.

Chris Case 51:36

Wow.

Trevor Connor 51:36

Not even in the 90s.

Chris Case 51:38

That’s amazing, I could see how that would be like, oh my god, I can actually do something with this information now and see it, quote, unquote, see it.

Trevor Connor 51:49

Did you have one of those? The Polars where it was an IR interface, so beam of light to transfer the data to your computer. So, you would sit there for 10 minutes trying to line up the heart rate monitor with a little IR interface on your computer.

Chris Case 52:04

I’ve never even heard of such a thing.

Jeff Winkler 52:06

No, I never did it.

Trevor Connor 52:08

Oh, God. I had that for years.

Jeff Winkler 52:10

No, that epitome of tech on the bike was like the simplest of cyclo-computer, right? It was speed. The Avocet used to make a cycling computer that was ubiquitous, I mean, thing was so unsophisticated, you know, but it was on every bike. And if you see even pros from like the 80s, and you’ll see those are on there, you know, and they came in all different colors. It was a little bit like a swatch.

Chris Case 52:40

Right.

Jeff Winkler 52:40

Version of a bike computer. But all the developments, maybe with certainly data recording and analysis with heart rate, and then eventually power meters came after my competitive time, quite a bit after my competitive time.

Chris Case 52:59

Let’s jump over to the power meter, shall we? And talk a little bit about what those looked like when you were racing. You didn’t have a power meter on the bike, but maybe in the lab setting, you did. Is that true?

Power Meter Today vs. in the 80s

Jeff Winkler 53:11

Yeah, I did a number of tests with a little bit I actually there was a CatEye that machine that was available, the most typical one was the Monarch, which is a non-digital, you know, and we’ve all seen those in the exercise physiology labs. But CatEye made one that was I mean, even by today’s standards wasn’t really that bad, although now that I’m thinking about it, it might have actually printed out the data, almost like an old-style calculator with the paper roll on it, you know? But you would typical lab testing, right? You would do VO2 testing, you do lactate testing, you could do RAMP tests, I mean, you could do the old-style Konkani with just a heart rate monitor and controlled RAMP that was done, you know, it probably was not done as much simply because there was no way to put great action, you couldn’t take that data and do a whole bunch with it, right? Because you couldn’t do it on a day-to-day basis with your training. So, it was more of a periodic thing or year-to-year thing where you would check where you were.

Jeff Winkler 54:29

I guess one thing I do remember doing with test results, was taking essentially the heart rate power curve, so the Konkani graph looking for the deflection points but then doing that at different points during the season to see which parts of the curve had moved more or less than the others to get feedback on, where has your training maybe you haven’t been focusing enough time because it hasn’t improved in line with other improvements, which may or may not have been an accurate way to go about it. But that was probably as sophisticated as I got. I remember most of my contemporaries, especially if you were up and coming, getting a VO2 test at the time was really not a thing you wanted to do unless you were Greg LeMond. If you didn’t have you, basically, you’re almost guaranteed to get a result that didn’t say you were going to be the next Tour de France winner. So, what team directors tended to do at the time was they looked at that, and they said, “Oh, well, you’re in the 60s. You’re never going to be anything.” Or you’re in the low 70s or mid-70s, like, maybe you will be a Domestique, you know? So, it was almost like a death sentence to do a VO2 test. Invariably, you had to do them in the offseason, so you were at your heaviest, and your form was at its worst, that was more my orientation to testing.

Training Based on Perceived Effort

Trevor Connor 56:00

So, I think there’s another, we are talking about power, there are a couple of really important but somewhat subtle changes that power brought about, brought about in training, and particularly in cycling. So first, it’s really important to understand that initially, most of our metrics, most of our ways of doing training, and particularly in the 80s, were all internal. So, talking about, you know, what’s going on in your body? So, is based on perceived effort, perceived effort is completely internal. The first real metric that we had was heart rate, heart rate is also an internal measure. The only external measure that you had was speed, and certainly, that was looked at quite frequently, because ultimately, a race is won by whoever’s fastest, so speed remains important. But power is an external measure, and I think one of the subtle changes you’ve seen, is an emphasis much more on external measures than internal metrics. That’s what’s really dominant right now we really think the way to train is by power, and a lot of people now don’t even train with heart rate monitors because they go well, why would I want that? Well, you want that because it’s an internal measure, telling you what’s going on with your body. So that’s, I think, one subtle change. That brought about another subtle change, that’s also very important, which is, as they were starting to do more and more exercise science research, it really started with all the research being on runners, because you needed an external measure, and before power, there was no external measure for a cyclist in a lab. If you put them on a trainer, their speed is zero. So, all you had was internal measures or runner, you could at least put them on a treadmill. And well, you can measure speed, I was not going to go deep in the weeds, but if they’re on a treadmill, they’re actually doing no external work. So, when power meters came around, all of a sudden, you had this great external measure for cyclists, and it was actually better than how you measure runners because as I said when a runner is on a treadmill, they’re actually doing no external work. So, you can’t measure work with a power meter, you can’t even when they’re on a trainer. So, you saw a shift in the research from being very running dominant, to actually for endurance sports, being very cycling dominant.

Does the Power Meter Improve Performance?

Chris Case 58:30

Has the advent of the power meter, has the ubiquity of the power meter made cyclists universally better?

Jeff Winkler 58:39

I’m gonna answer first with the hard way for us to know, right? Probably the best way for us to resolve this debate, in a practical sense, would be not to focus on the elite level athletes, but to look at sort of the mainstream competitive athlete, and that could be in triathlon or cycling, and ask the question, has the level risen? As a result of these advancements, including primarily the power meter? And I don’t know the answer to that, and it would be really interesting to say, well, to try to discover are the pros from the 80s and 90s, were they slower than the one-two fields today? Or the Master’s fields or the Cat4 fields or, you know, all of those levels? Because what’s probably the most different is the training, guidance, tools, and analysis that that group has. That’s what’s really different where the elite have always had access to the best available science and tech, you know, and I don’t know the answer to that. My gut says no, but I could be wrong.

Chris Case 1:00:04

Before you jump in, Trevor, because I know you have an opinion here, it feels to me as if there are like with most things, pros, and cons to the power meter. There’s more nuance to be found and utilized in training, but there’s also more data and people can get distracted by that, or overwhelmed by that, and so forth. So, it seems like the power meter has quite a number of advantages and quite a number of disadvantages.

Pros and Cons of the Power Meter

Trevor Connor 1:00:37

I would say my answer is used right a power meter is a remarkably powerful tool that’s great to have. Used wrong, yeah, I think it can get you distracted, it can get you off course, have you focused on the wrong things that actually hurt your training. To use it right actually takes a lot of experience and a lot of knowledge, and unfortunately, the things that are the most exciting and most appealing about the power meter, such as the big five-minute wattage you did, or what you did going up a climb, the things that we all love to see, tend to be the things that get you off track. So, at least with the athletes that I’ve worked with, that I have talked with, maybe it’s a 60/40 split, but I would say a little more than half, unfortunately, use a power meter in a way that I would describe as hurting the training, not helping the training. The 40% who use it right, it can make them, it could be very effective.

Chris Case 1:01:37

I would also suggest that given the athlete, you could take a particular athlete, you could say, okay, you’re going to use a power meter for one year, and then you’re going to take that power meter away from you, and you wouldn’t necessarily see any difference in their training, because they have that self-awareness, they have the feeling, they understand the principle, so on and so forth, and therefore, it isn’t a necessity that it be used to get to a high level. But other people would be completely lost without that information. Is that true?

Psychological Component of the Power Meter

Jeff Winkler 1:02:16

There’s a psychological component too, and I’ve worked with athletes that really thrive on having that feedback loop that power on the bike can provide and heart rate to a certain extent as well, you know, where other athletes that actually breaks them down over time, that constant focusing on that feedback, burns them out. And so, you know, I’ve often asked myself is at the especially at the elite level, do you have a different personality or a different mindset of athlete thriving today, versus the ones that thrived in sort of the pre-technology days? More to Trevor’s point, it is absolutely a useful tool, and the challenge is how to apply the tool the right way, it’s you know, it’s if it’s a hammer, you don’t then just drop all your other tools, and, you know, use a hammer to, you know, to do everything, it’s a hammer that has very specific use, and provides value to the training process if you exploit it for what its, you know, its best value.

Trevor Connor 1:03:28

So, I’ll give an example. I’m interested whether you agree with this, but sometimes it helps with an example of what I would consider good use and bad use. This example will be as myself just to show that even though I am aware of these issues and try to tell athletes not to use it the wrong way, there is such a huge temptation, I find it hard myself not to use it the wrong way. So, I have these hill repeats that I love to do, and the hill repeats are all about consistent execution, you do a certain number of repeats, you want them all to be about the same intensity. So, when I do them right, I go out, I do my first interval more by feel, get a sense for where I’m at that day, and then at the end of the interval go, I think x wattage is about right, and kind of target that use heart rate a lot, so I want to be right around my threshold heart rate, and can get through what I would consider a very successful set of intervals that were executed well and are going to produce the training adaptations I want. That to me is effective use of the power meter. The ineffective use, which I would say I get caught up in at least half the time, is when I go out and I go, okay, well, it’s March 15, and back when I had a good year and whatever year right in the middle of March, I was doing these intervals at x wattage. So, now I got to go out and do that, and if I’m out there and I go, no, I’m 10 watts below what I was doing that March. You try to ramp it up and go to intensity that, you know, RPE is telling you, this ain’t right, you’re not getting through the set, and you ignore it because you have to prove that you’re as strong as you were a few years ago, that’s bad execution. It’s really easy to get caught in that game, same thing, have one day I go out and do them and I was feeling really good and put out some banner wattage, I came out a week later to do them, I want to hit that wattage again, but that’s probably not going to happen.

Chris Case 1:05:27

Yeah, in that case, you’re using a number to express or equate with success or fitness or the form that you’re hoping to have or realize, and sometimes that’s just going to take you right off the track.

Trevor Connor 1:05:41

Right.

Chris Case 1:05:42

From what your actual goal is.

Trevor Connor 1:05:43

You’re targeting a number instead of saying what is right for the best gains from these intervals. The one nice thing in the 80s is it was really simple, you didn’t have any of the things, so you’ll learn the feel, and then every time you went out and did my feel and had no idea that, well last week I did these 20 watts higher than I did this week because you didn’t have those numbers.

Chris Case 1:06:03

Yeah, I suppose you could make the argument that your brain isn’t without its flaws either, and so the feeling you had of success on one day could be very different from the feeling you had the other day, and if you had a measure, you might be hitting the same watts.

Trevor Connor 1:06:18

Well, my brain has many, many flaws. We will do a whole episode on that later.

Chris Case 1:06:22

That’s another show. Yeah.

Jeff Winkler 1:06:25

I think you’re right, though, I think it shifts the focus. I think that in pre-tech days, you had to embrace the idea that, hey, I’m working on a system, and implied in that sort of purpose was the underlying systems not that exact anyway, right? I don’t even think today, we can say, well, if you were training five watts higher, you’ve got this demonstrable, measurable difference in terms of an adaptation. So, you knew that like, okay, my goal is to stress a particular system, and that was the focus. Now with the advent of a very precise feedback mechanism, I think we’ve been pulled away from the focus of stressing a system to achieving an outcome.

Trevor Connor 1:07:20

Right.

Jeff Winkler 1:07:21

And I think that’s problematic.

Trevor Connor 1:07:23

And the flip side, I’ll give you, I agree with you completely, 5-10 watts really isn’t going to have possibly any impact on the training adaptation, except if you’re targeting 10 watts higher than you can actually do those intervals at, and you’re supposed to do five repeats, and at two and a half you blow up and then go home with your tail between your legs, because you couldn’t get them done. That is going to have an impact on your training.

Jeff Winkler 1:07:50

Right, right. Yeah, and you couldn’t do that without the power meter, because you wouldn’t be chasing a number, you’re just chasing a sensation. You know, even so, again, it’s solvable. It’s just we have to always sort of take power and filter it back through the purpose goals and equating it with sensation. I rarely, I’m telling my athletes to hit their best I don’t want I mean this is a little bit my bias from having a competitive background is like, I don’t want to hit my bests in training, I want to hit my best in a race. We all know that motivation is not infinite, right? Anyone who’s raced a full season knows that motivation is a scarce resource, and you have to preserve that. And so, if you go out every training session, that’s a hard session and you go for your best possible effort, I don’t think you can have your best efforts all season in the races when it matters, but that’s a racers bias. So, this like loops a bit a little bit back to where we began the conversation is that maybe chasing numbers is good for certain types of athletes or participants. If your goal is to track improvement and progression, and it doesn’t have anything to do with podiums and placings, then this is a perfect tool, because you can see improvement.

Chris Case 1:09:27

So, let’s get back to our tally here. Heart rate monitor sounds like the monitor itself, it’s a toss up because it hasn’t changed much. However, the analytics has changed considerably, and there have been vast improvements there. So, tick in the box for the 2000s. Power meters, obviously didn’t really exist in the 80s, so you can’t give it there. So, let’s give up to the advent of the power meter to the 2000s. Dare I say that it’s a toss up between the application of them? Probably not, it seems like the use of the power meter is a good thing, if used correctly.

Trevor Connor 1:10:17

But a bad thing of used wrong. So yeah, I would kind of give that a equal.

Trevor Connor 1:10:24

We asked Dr. Andy Coggan, and cycling coach Hunter Allen, authors of Training and Racing with a Power Meter, their thoughts on what’s changed. They agree the principles are the same, but obviously feel a lot has improved since.

Dr. Andy Coggan and Hunter Allen: Thoughts on the Evolution of the Power Meter

Hunter Allen 1:10:36

The physiology is the same, right? I mean, that’s not changed, right? Nothing has changed from that perspective, you know, and periodization is still there, I mean all of the same principles are there, but the, you know, the way that we train is definitely changed. I think that’s where, why we see, you know, big improvements in athletes, you know, over shorter timeframes. I mean, that’s a huge difference, where we can now start to reach people’s potential sooner, and then we can get to closer and closer to their maximum potential, through training, with more scientific methods. You know, we’re quantifying power data through measuring, understanding the demands of the events. I mean, heck, we didn’t even know how many intervals you needed to do in a criterium, you know, what were the demands the event? We thought we knew, but then we got power meter, and we started defining exactly the demands of the event, oh, cool, what kind of workout would mimic this? Oh, well, I should do a microburst workout, and created workouts that are specific to the demands of the event. So, in that way alone, it’s allowed us to train differently.

Trevor Connor 1:11:49

So you’re saying some of the fundamental principles probably haven’t changed, but the specificity with which we can train the way we can tailor workouts has improved dramatically?

Hunter Allen 1:12:02

Absolutely.

Dr. Andy Coggan 1:12:03

Yeah, you know, ways of training, sometimes people make the same point about power meters, Eddy Merckx didn’t need a power meter ect. I often argue that there’s sort of like, three things that athletes take a path either, you know, there’s the people who never figure out how to prepare for events and reach their potential. There are people who figure it out pretty quickly on their own. Then there are the people who it takes a long time. Well, the people who’ve never figured it out, I mean, they’re clueless, and you know, they buy a power meter, it’s a full on toy, and they don’t necessarily benefit. And the people who figured it out pretty quickly, well, they don’t necessarily benefit directly, or immediately that much, but by hitting the middle group, those that figure out eventually, this is their best way to train by speeding up that learning curve, you don’t necessarily make the fastest, faster, but you make more people fast. And then that means everybody has to up their game, because the competition has become more intense. So ultimately, the people who are already fast, are forced to get faster, but it’s because of the groundswell from below.

Trevor Connor 1:13:24

Right.

Dr. Andy Coggan 1:13:25

That is aided by data and direction on how to use that data, and good coaches like Merckx.

Trevor Connor 1:13:33

So, you brought up Eddy Merckx, so here’s a real hot take question for you. He was obviously a genetic freak, but do you think that with today’s training technology, could he have been even better?

Hunter Allen 1:13:50

I would think so. I mean, I would think that that, you know, he, he would have trained, you know, smarter, he would have trained more specifically, and he could have achieved even a higher level of FTP. And I mean, gosh, you know, he was incredible at peeking when he wanted to peak, but there were times when, you know, he didn’t have to, and he still was so good, you know, he was winning when he wasn’t peaking, right? That’s why he was such a mute, so yeah, I would say so.

Dr. Andy Coggan 1:14:25

My initial reaction was, I have no idea, and then I thought of his nicknamed the cannibal, and thought, well, how can he get any better? And then I thought of how he prepared for his hour record attempt, and you go, oh, you could have gone so much further.

Trevor Connor 1:14:39

Yes.

Dr. Andy Coggan 1:14:39

You know? He didn’t climatized, you know, a few half-dozen workouts or whatever, with a hypoxic gas mixture. So clearly, you know, plus going after what the 5k and 10k and 20k records on the way is not the best way to pace yourself. You know? There’s a perfect example.

Trevor Connor 1:14:58

Didn’t he like ride night before at altitude and like grab a couple beers and then go to bed or something like crazy like?

Hunter Allen 1:15:07

I know, like a few hypoxic workouts before he traveled but if I were going to altitude, I take it a little more seriously than this.

Chris Case 1:15:19

How do we take all of this conversation and give people something to chew on to digest to put into practice here?

Trevor Connor 1:15:28

Well, I’ll give you the final winning on the scorecard here.

Chris Case 1:15:32

Yeah.

Trevor Connor 1:15:32

He said hairbands.

Chris Case 1:15:34

The 80s had hairbands. Yes, this is true.

Trevor Connor 1:15:37

80s win.

Chris Case 1:15:38

All right.

Jeff Winkler 1:15:39

And MTV.

Chris Case 1:15:40

Jeff, did you have a mullet when you were racing over in Europe?

Jeff Winkler 1:15:43

Not every year, but some years. Yes.

Chris Case 1:15:46

Excellent. Very good. Then that hair wins.

Trevor Connor 1:15:48

How can you race and train in an era without Guns and Roses?

Jeff Winkler 1:15:52

Well, I mean, the old helmets, the leather helmet, I mean, they’re called a hairnet. I mean, of course, it’s all about hair.

Chris Case 1:15:58

So, what are some other take homes here for people to walk away with?

Jeff Winkler Takeaway Message

Jeff Winkler 1:16:04

I suppose I’d like to, to just say that, like you can’t write off the old school. I mean, the old school has some valuable contributions to the training process, and of course, you know, it was interesting, when I came back to coaching with the existence of all of these tools and techniques and systems for analysis, I had kind of a harsh reaction Initially. I immediately saw, oh, the value of the feedback is great, you know, to be able to put a number, you know, with power. But some of the analysis that has arisen out of having all of this data, my first reaction was, this is like, it seems like a bit of false precision, that we don’t fully understand the systems that are operating, and so while we are measuring them, we may still not really be to the endpoint, right? You know, we’re early days in terms of understanding the physiological systems and then linking them to the tools that we measure. So, I think the challenge is not to get lost in this precision and data and analysis, because it is not 100% accurate, and it’s actually hard. It just creates new questions, which maybe is not moving us always forward, right? We’re just getting mired, where maybe we’re mired with a lack of information. Now we’re mired with too much, or a tendency to focus on things that may not really be that productive to focus on. I think that probably in another 40 years, it’s going to be a different story, and I think that’s going to be big data as a result of big data, and machine learning, and what have you, I think that’s probably where we’ll start to really understand the trends and the underlying data that it’s very hard for us to parse out right now.

Chris Case 1:18:19

It sounds like what you’re saying is, if we took a step back from where we’re sitting and looked at the playing field that we’re in right now, we are a little bit lost in the forest, there’s so much information, so much data to be used, we just aren’t exactly sure yet how to use it best. In some ways, what we’re collecting is not as accurate, if you want to use that word, as it could be in 40 years, well, we’ll see drastic changes it might be in 10 years we’ll see drastic changes in the improvements of data analytics far surpasses where we’re at right now.

Jeff Winkler 1:19:07

I think that’s at least partially true, right? We’re struggling to extract meaning out of the data and the tools that we have. We’re certainly successful at certain levels, but I often feel as if we’re looking, and we certainly are seeking precision like we want to link what we see on the sensors to an underlying condition and then sort of change how those things interrelate and do a better job of training and developing fitness. But you know, anyone who spends time reading studies on exercise science, you’re going to be left with this idea of we don’t know what we’re doing, right? Because we get conflicting results a lot of the time, and it’s because of the details, we don’t fully understand the black box, I mean, or there’s at least a certain aspect of a black box to things still with the body. But that doesn’t mean the tools aren’t useful, you just have to just don’t think they’re gonna answer all the questions, but they do a very good job of answering some questions.

Chris Case 1:20:24

You coached CU for six years. So, athletes ranging, you know, late teens, early 20s, I guess you could say. I would assume that you were collecting data on them? I’m just curious how much they were participating in the analysis of that data? Or if you were, I don’t, protecting is maybe not the right word, but how much were you sharing with them? Or how much were you keeping that information to yourself, in a sense, so that they didn’t get distracted by that? Or was it a case-by-case basis, even at that age?

Jeff Winkler 1:21:07

Well, the answer comes from the structure of collegiate bike racing, while CU was a very successful program, it was a club program, they don’t have any resources. So, that was not going on. Where if you take a varsity program that has allocated resources, they have full-time coaches that it’s, you know, that’s what they do, and they work with a fixed, they recruit their athletes, and they have a fixed number of athletes, and they’re filtering off the top, if you will, and they’re working with the more serious athletes, they’re going through those processes, and they have the tools and resources to do it. You take a CU, which is the largest collegiate program in the country, when I was working there, you have 150 athletes, with one part-time coach. It’s impossible, you can’t do it, even if they were all serious. But in that, 150 riders, you also have a bigger spread of interest level, you have people that are, they’re not trying to become a pro, you know, this is fun, especially on the mountain bike side. They enjoyed it, and probably they won’t do it after college, but there’ll be a participant in the sport. So, rather than to belabor the point is there was not a lot of that done. Maybe the subset of A riders, who were particularly engaged and we’re looking to, you know, move beyond the collegiate level, there was more focus on that. But I felt for me a lot of what the cool thing about collegiate was that you were there at all the races as the coach, and you had the opportunity to be the in-person coach, almost like team director role more, and so I felt like I was making more contributions from a race craft perspective than from a technical training perspective, and many of them had their own coaches anyway.

Chris Case 1:23:28

Sorry to sidetrack us there, Trevor, what take-home messages Would you like to leave listeners with?

Trevor Connor Takeaway Message

Trevor Connor 1:23:35

So, I’m going to go back to the scorecard which wins the 80s or then or now. I’m going to say it depends, allow me to explain that. So, if we go back to how we started this whole episode, we talked about the principles, and the principles haven’t really changed. And the one thing that was nice about the 80s was that was really all you had, and it kept things simple/

Chris Case 1:24:04

Not a lot of clutter there.

Trevor Connor 1:24:05

And you could focus on the principles. Everything that I think has been introduced since then even things that we think of as being huge, like power meters, or the ability to analyze all this data that most people didn’t have access to until recently, all really just fine tune how you execute the principles. But as we said, they have that danger of you get so caught up in all the trees, you forget the forest. So, if you’re really focusing on all the numbers and the metrics and anaerobic threshold vs. FTP, vs. MLSS, and forget those principles, then I’m gonna say 80s win, it was simple, you focus on the principles.

Chris Case 1:24:50

Right.

Trevor Connor 1:24:51

You were probably training better. If you can stay focused on the principles and then use all that data to really hone in and focus on how you are training based on the principles, then I think now wins.

Chris Case 1:25:06