I like to say I’ve “graduated” to the realm of ultra-endurance competitions and events—efforts I define as lasting more than eight hours, and often last for days or weeks on end. (Think: long gravel races on one end of the spectrum and bikepacking events on the other.)

For various reasons, the presumed volume of training and experience needed to excel at these types of races prevented the younger version of myself—spry as I was, and full of fast-twitch muscle fibers—from even considering these events an option. I’m certain I’m not alone in having been intimidated by the prospect of transforming myself into an ultra athlete.

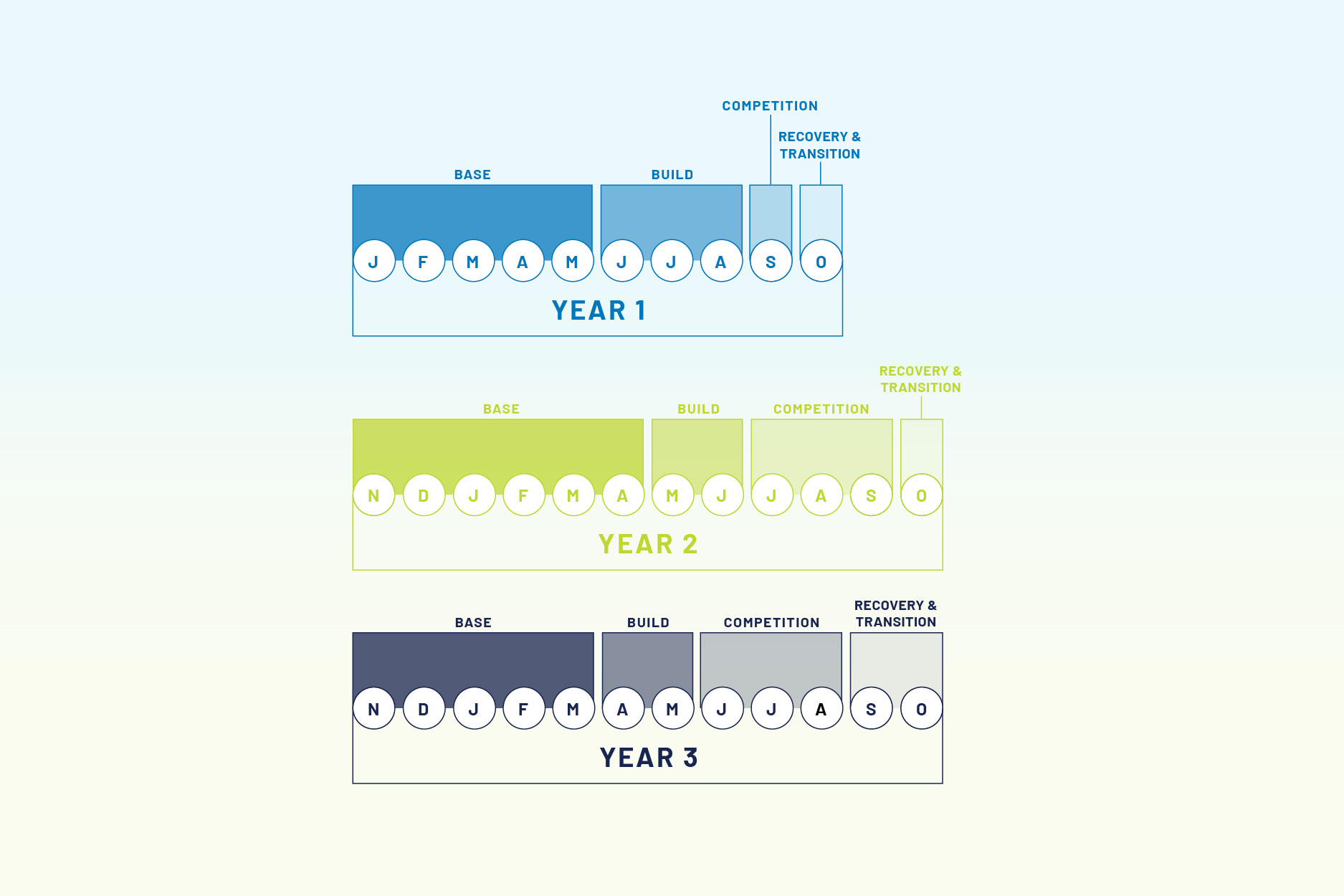

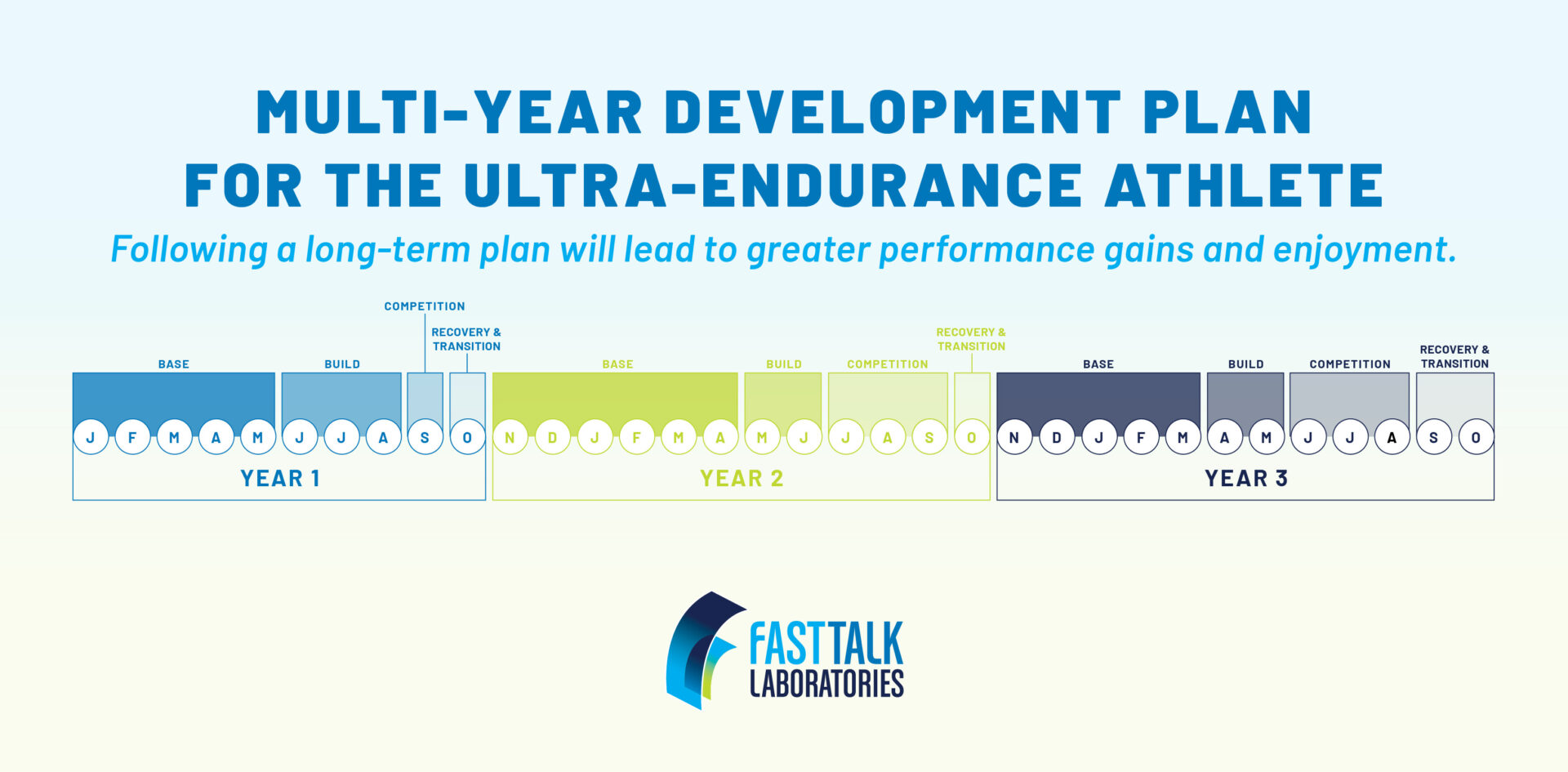

But volume and experience aren’t the only things an athlete needs to transition to this competitive landscape. A multi-year development plan can substantially improve the pleasure and effectiveness of transforming into an ultra-endurance athlete. It takes sacrifice and compromise: To achieve your full potential for going really long, you will likely have to sacrifice short-term goals for long-term development.

Transforming into an athlete who can muster the stamina for 12-hour races or events that last days on end doesn’t happen in a season. Some physiological attributes can only be developed by taking a step back and expanding the timeline of progression from months to years. Furthermore, the rate and trajectory of your progress is a function of various factors: your current fitness level, genetics, and the amount of time you can devote to training.

How we develop fitness

Despite what many athletes believe, there is not a linear relationship between training and fitness—you do not get “stronger” at the same rate throughout the training process.

The relationship is, instead, curvilinear. Initially, it takes very small amounts of training stress to see substantial gains in fitness. Athletes experience this at the start of the season or after returning from an injury. However, as your fitness improves, the rate at which you make gains begins to decline. In other words, it takes increasingly more training stress to see even small gains.

RELATED: The Relationship Between Performance Level and Training Stress

In simple terms, by doubling your annual training volume, you will not double your fitness or performance gains. The improvements will be significantly less. Eventually every athlete reaches a plateau where no matter how hard they train, they won’t see any further improvements.

What’s critical to remember is that by increasing your training volume, you also increase your risk of overtraining and/or injury. Initially, the risk is very low with low training stress. But as training stress increases, the probability increases.

Eventually, if you increase your training volume too quickly, your fitness will plateau and your risk of overtraining peaks. This is not a recipe for long-term or even short-term success. This is when taking the long view to reach your full potential is most critical.

Setting your trajectory

Every athlete plateaus at some point. In many ways, this has to do with their genetic potential. How you train is of utmost importance for determining how close to that potential you come. And the most important aspect of training for the ultra-endurance athlete is that low-stress, high-volume endurance base phase. The length of that phase has a direct impact on the height of the plateau and, thus, your full potential.

In essence, base work sets the trajectory and arc of progress. Once you start doing higher-intensity training, the trajectory will begin to level off and head toward the plateau. Therefore, the more base training you do, the higher your potential plateau becomes. This is particularly true for ultra-endurance events.

The moral of the story, then, is to make base training long enough to allow for a high plateau without allowing for the monotony and repetitiveness of long, slow rides or runs to sap your motivation. When your plan is stretched across multiple years (rather than compressed into a single season), this is difficult to do.

Which is why it’s important to remember that each athlete has both a genetic potential and a seasonal potential that will change year over year. With a proper multi-season plan, well-trained endurance athletes will start the next season at a higher level than the previous season and be able to raise their plateau.

It’s also important to note that with each year, the potential benefits from base work decrease. This has advantages and disadvantages. First, well-trained athletes can achieve a high level of fitness with a lot less base training than beginner athletes. However, this also means it takes a lot more work to see small gains. And with that increase in workload comes a greater risk of injury or overtraining.

Perhaps the most important lesson to take from the relationship between training stress and performance is that as athletes progress to a higher level, the goal should not be to train harder but to train more intelligently. Choose workouts wisely, but also place more focus on rest and recovery.

These purposeful training practices improve the potential benefits of higher stress levels while still avoiding injury. Ultimately, this principle allows us to set expectations for the progress you should see during any given season and across multiple seasons.

Building a multi-year development plan

Multi-year development plans are often utilized with Olympic athletes, since they hope to peak on a four-year cycle. Observing how those athletes and coaches create plans to peak years in the future can offer tips and lessons for anyone, regardless if the Olympics is not the goal.

From the research, anecdotal and otherwise, an athlete’s VO2max doesn’t change all that much throughout life. Meanwhile, biochemical changes brought about by high-intensity training happen relatively quickly.

There are other attributes like stamina, durability, and so forth—a product of physical changes rather than biochemical—that are harder to quantify, and these take years to maximize.

Sondre Skarli, a sports scientist consultant at the Norwegian Olympic Committee and Federation of Sports, has extensive experience coaching athletes and building multi-year development plans. Formerly an elite speedskater, he was once a student of Dr. Stephen Seiler.

Dr. Seiler notes that the changes you can only see from long-term endurance training start with the heart: It is about maximizing cardiovascular output.

“You want to drive huge venous returns to the heart,” he said. “You want to get huge filling, so you stretch the heart. You expand stroke volume slowly, then it seems to respond by, number one, adding volume of blood; and that increases the muscle—literally you get cardiac hypertrophy.”

Seiler explained that a positive cycle begins once stroke volume increases. First, the athlete develops more mitochondria as they tolerate more volume. Consequently, they further develop the ability to work over longer periods.

“[The question] becomes how rapidly you can increase training volume over time, because that’s a double-edged sword,” he said. “More volume creates more stimuli, but more volume also can lead to more stress and breakdown.”

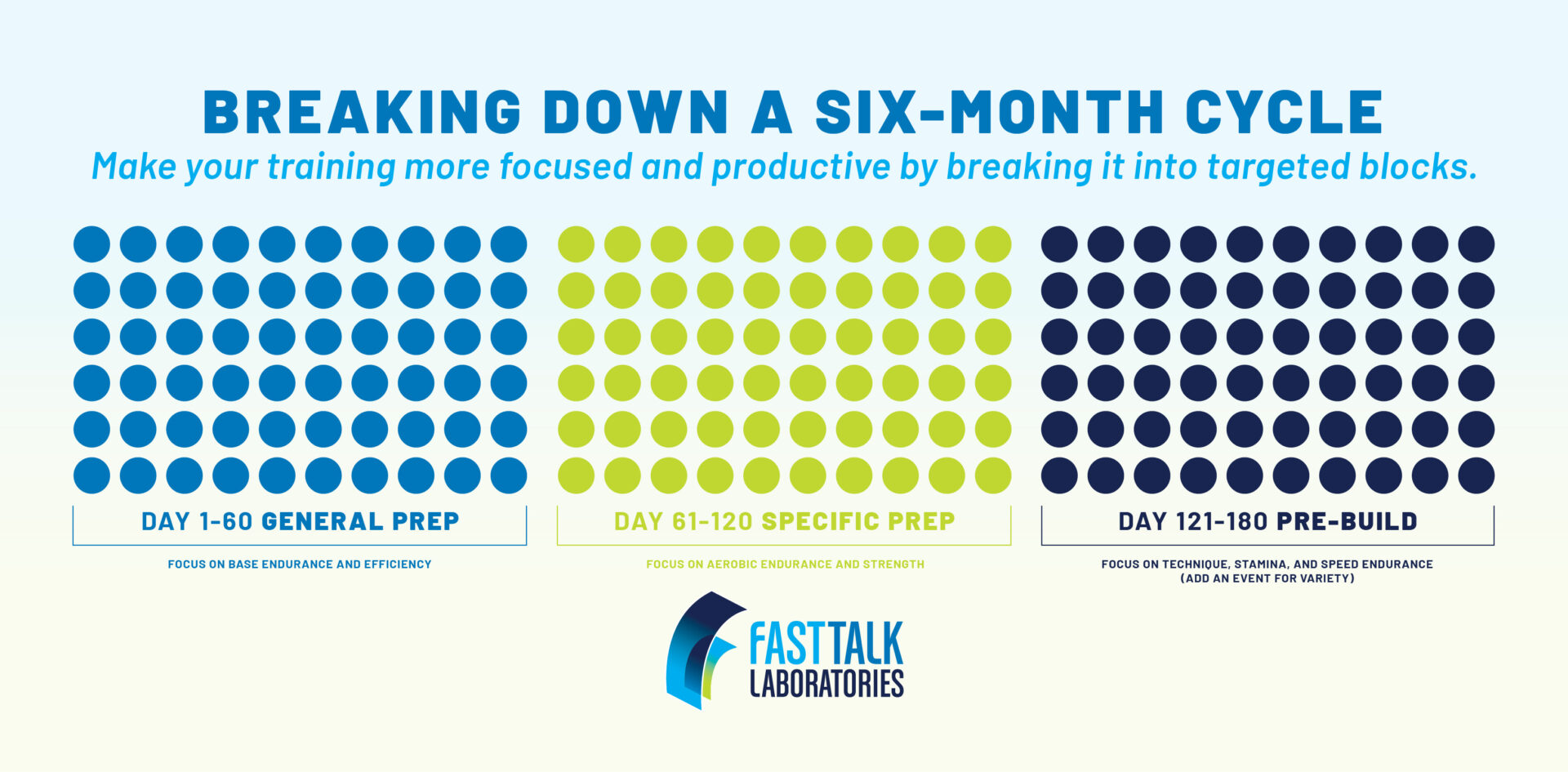

Both Seiler and Skarli stress the importance of setting smaller milestones as a way to cope with the monotony of this slow build. They recommend athletes create multiple opportunities for success. This creates an area to focus on for several weeks, with a particular purpose that builds to a crescendo. Then the athlete can get back to grinding away at more work.

By breaking up a six-month cycle into three chunks, for example, athletes and/or their coaches can conduct different tests, focus on various milestones, and complete different non-target events to gain feedback—all while adding variety to the regimen.

“I would never recommend a long-term plan with only a goal for the long term,” Skarli said. “You should always have short-term goals as well. And you should have short-term goals in physical development, in test results, in competition results, in training results, maybe in nutrition or sleep patterns and stuff like that.”

Get creative to find ways you can develop and measure how well you are meeting your progress goals. Remember that most athletes don’t normally achieve all their goals. But if you make some of them, then you can look back and see the success and continue to look for ways to improve.

Placing trust in the plan might be one of the most difficult (yet most critical) aspects of long-term development. It takes time and patience. It would be easy to give up hope if you only looked six months ahead. That’s why you should make time to determine if that plan is appropriate and whether you are hitting enough of the marks you set out to achieve.

“It’s really all about trusting that plan,” said Fast Talk Labs co-founder Trevor Connor. “Because when you’re looking way ahead, there are going to be plenty of points where you are going to wonder, ‘Am I on track? Am I doing the right thing here?’ You’ll go to that group ride and get killed and go, ‘Wait a minute’—even if you tell yourself beforehand, ‘This is the way it’s going to be. I’m training differently.’”

While sticking to the plan is critical, being willing to adjust—for example, because of injuries, sickness, or other circumstances—is just as necessary. It’s easy to fall into a trap, as Skarli did when he was in the early days of his coaching career. When you spend so much time and energy creating the plan (or your coach does), you (or they) might fall in love with it. You might find it hard to veer from it.

“You have to be true to the plan,” Skarli said. “But the plan is never better than the execution of the plan. It’s better to have a bad plan with good execution than a good plan with bad execution. You have to always be willing to make some adjustments and listen to the body. Because this is not machines [we’re talking about]; it’s human beings.”

When asked what the key to success is for long-term development, all three coaches agreed that time was of utmost importance. Investing more time in training was at the heart of success. Every day, every workout, takes you one day closer to the goal.

References

- Støren Ø, Helgerud J, Sæbø M, Støa EM, Bratland-Sanda S, Unhjem RJ, Hoff J, Wang E. The Effect of Age on the VO2max Response to High-Intensity Interval Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Jan;49(1):78-85. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001070.