Manual therapy is integral to most athletes’ training plans. For instance, weekend warriors and the casual rider might get the occasional massage. And when recovering from an injury, we’re bombarded with options: Do I need dry needling or acupuncture? Should I see a chiropractor or a PT?

Depending on who you ask, you can get widely varying answers as to which type of manual intervention you should choose, and what type of specialist you should see.

This article will break down some of the major benefits and misconceptions of different types of manual therapy. Not all manual techniques are created equal, and they shouldn’t be used interchangeably.

Deep Tissue Massage

What it does

Massage provides deep pressure to the body to manipulate the soft tissues into giving you relief from pain and stress.

Does it work?

Good news! There are many low-evidence studies that suggest participants feel deep tissue massage decreases musculoskeletal pain and general stress (1). By stimulating deep pressure receptors, your body can have a big shift in cortisol levels and enhance vagal activity (2).

Does massage change your muscle “tightness,” though? There are some interesting studies that demonstrate how massage to the musculotendinous junction of the hamstring can substantially improve participants’ passive hip flexion (picture a long-sitting forward fold) over 12 weeks (3). That being said, there was no structural change to the “stiffness” of the hamstring. This has been tested in many different groups, and I can confirm: There has yet to be compelling evidence that massage improves muscle extensibility in the short- or long-term.

When should I get a massage?

If you’re in pain, there is good evidence that this can improve your acute symptoms (3). Just keep in mind that most studies point to the fact that exercise interventions give you better and faster results compared to massage interventions (4). Evidence that massage improves your recovery or changes your tissue extensibility is low, but if you find it useful for your pain and stress levels, this is a great intervention.

We’ll get into this a little more later, but let me drop a hint here: If massage improves your pain, that can give you the paradigm shift needed to double down on motor control and exercise interventions to break your pain cycle.

Dry Needling

What it does

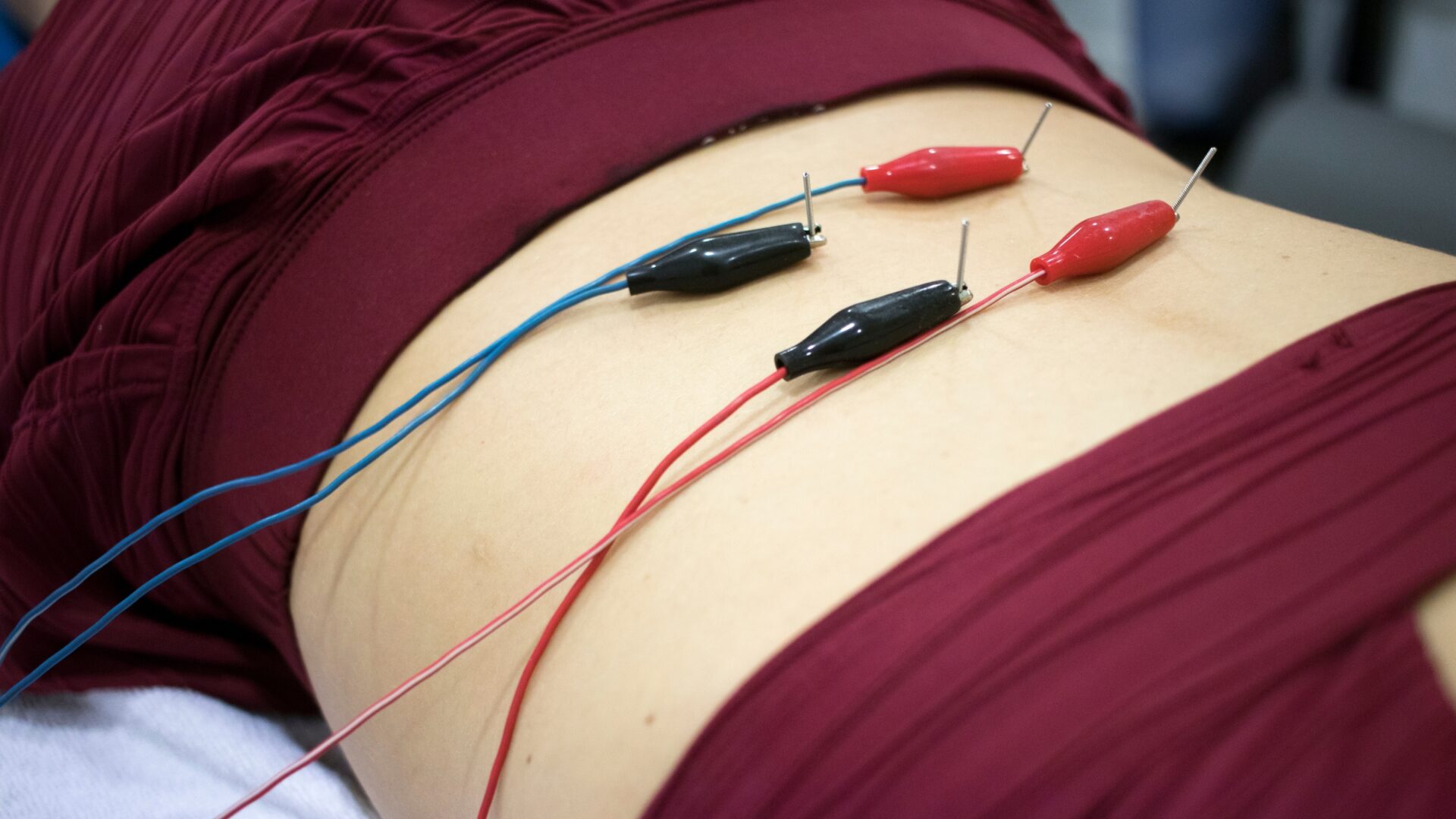

Dry needling treats myofascial pain by directing a thin needle into a myofascial trigger point. It can give an analgesic effect to the trigger point and surrounding muscle tissue by inhibiting the central nervous system and releasing endorphins and enkephalins (6). The result in the short term is an increase in pain pressure thresholds and a “loosening” of the muscle. With additional electrical stimulation applied to the needle, there is low evidence that you can modulate muscle sequencing and motor control.

Does it work?

Okay, I’ll admit it: I love dry needling. With the added benefit of saving my hands from hours of massage work, I find I can get within-session results for patients. Anecdotally, I can see a change in mobility and stability in addition to the beneficial pain changes. There is more evidence coming out that supports what I see in the clinic, but there is a paucity in the literature due to its relatively recent climb in popularity.

But the question comes down to this: are the results long-lasting? My take: sometimes. More often than not, though, dry needling is not the be all and end all. If you don’t couple dry needling with exercise to change your movement patterns, your pain or movement pattern will not shift.

How is this different from acupuncture?

There isn’t a succinct answer to this question. There’s an ongoing debate about what crossover exists and the scope of practice of a doctor doing dry needling versus an acupuncturist doing acupuncture.

Dry needling tends to treat myofascial trigger points while acupuncture could be treating different structures. We use the same needles and might have similar goals with our clients, but I’ll just leave this by saying they can be very different, and I won’t pretend to be an expert in when and how to get acupuncture.

When should I get dry needling?

Dry needling can treat pain and give you the feeling of improved mobility (or stability, depending on how it’s applied). I’d recommend seeking out dry needling before you get injured, like when you notice a niggle of pain or an asymmetrical movement pattern that could become something bigger later on. It can also be used while in the rehab process.

If you have a well-calibrated training plan, you do not need to keep dry needling forever. If you’re moving well and relatively pain free, I would trust your exercise plan over relying on routine dry needling.

Manipulations

What it does

This is usually associated with chiropractors, but doctors of physical therapy and doctors of osteopathy also do these when it’s clinically appropriate. What I’m describing here are high velocity, low amplitude thrust techniques. If you’ve experienced these, you probably remember a “pop” sound that accompanies the pressure.

Does it work?

Yes, it does! The evidence is pretty clear. When a patient undergoes a spinal manipulation, for instance, they can have an improvement in pain, mobility, and strength (6). Yes, you read that right: manipulations can serve as a neurological “reset” to the spine and the related muscles that are innervated by the segments of the spine.

When should I get a manipulation?

You should seek out a provider who will do a careful and thorough exam and have them decide if it is medically appropriate. There are a few reasons I would choose not to apply a thrust manipulation to a patient—for example, if the patient isn’t comfortable or has had substantial pain for some time.

I would not recommend getting everything you can “popped.” Find a provider who has an explanation and targeted approach to the tissue you want treated. Manipulations are effective during the rehab process to modulate your pain and “reset” your tissue before exercise interventions.

Cupping

What it does

We’re talking about dry cupping here, which means we aren’t puncturing the skin. Cupping has been around for centuries but only became popular in the Western sports medicine world in the last 10-15 years. There are several theories about how cupping works: it dilates capillaries in the area to improve microcirculation, it can decrease muscle tone and improve healing, and it can decrease myofascial trigger points and pain (5).

Does it work?

More evidence on application to different types of musculoskeletal conditions is certainly needed, but I would say that yes, cupping works! I personally find it effective on more chronic pain, as it can cause some micro-aggravation to the related tissue and improve healing and mobility to the area. There’s another conversation to have about applying cups to an athlete and then having them mobilize the area with movement, but my summary of this is that athletes tend to have at least short-term extensibility gains, and this is an excellent primer before getting the athlete moving with exercise.

When should I get cupping?

I recommend this for larger swaths of tissue that are giving you trouble, like your iliotibial band or your paraspinals. Of all these interventions, cupping is the one I’d be most comfortable with demonstrating to a patient how to do and having them cup on their own.

Essentially, you can use this in conjunction with foam rolling or as a more pointed intervention for injury. It’s part of a larger picture: I would recommend cupping followed by your mobility routine or exercise for the day.

Who Should I See?

If you’re trying to decide if you should see your massage therapist, physical therapist, chiropractor, or orthopedist, let’s walk through the basics.

There are a lot of good practitioners … and some bad ones

I want to be as provider-agnostic as possible here. What I’ve hinted at above is this: If you see a provider of any type and they give you a manual intervention but don’t give you tools to change how your body moves (exercise focusing on motor control), you might not be seeing the right person.

Who should I avoid?

If a provider tells you to keep coming back because you’re “out of alignment” or “run super tight,” that provider is running a great business, but at the cost of getting you better. You should ultimately be looking for a provider who eventually does not want to see you anymore because you are recovered. Your body has a massive propensity to change. No one is symmetrical, and we all have funky alignments. Do not keep going back for years to the one person who claims they can continue to “fix” you—that’s your body’s job!

No matter what manual technique you prefer or choose to seek out, it can be an excellent supplement to your exercise and movement routine. No manual therapy will make or break your athletic performance. I strongly recommend seeking out a team that can give you all pieces to this puzzle: excellent and well-informed manual interventions, specific motor control exercise, and general conditioning. Manual therapy can be hugely effective only when used in conjunction with movement elements.

If you need recommendations or want to do a virtual consultation, you can sign up here for my waitlist.

References

- Pain Med. The Impact of Massage Therapy on Function in Pain Populations—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials: Part I, Patients Experiencing Pain in the General Population. 2016 Jul; 17(7): 1353–1375. Published online 2016 May 10. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw099

- Complement Ther Clin Pract. Massage therapy research review. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 Aug 21. Published in final edited form as: Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016 Aug; 24: 19–31. Published online 2016 Apr 23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.04.005

- Akazawa N, Okawa N, Kishi M, Nakatani K, Nishikawa K, Tokumura D, Matsui Y, Moriyama H. Effects of long-term self-massage at the musculotendinous junction on hamstring extensibility, stiffness, stretch tolerance, and structural indices: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther Sport. 2016 Sep; 21:38-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.01.003. Epub 2016 Jan 28. PMID: 27428533.

- Beumer L, et al. Effects of exercise and manual therapy on pain associated with hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50:458–463. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095255

- Derek Charles, Trey Hudgins, Josh MacNaughton, Eric Newman, Joanne Tan, Michael Wigger. A systematic review of manual therapy techniques, dry cupping and dry needling in the reduction of myofascial pain and myofascial trigger points. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Volume 23, Issue 3,2019, Pages 539-546, ISSN 1360-8592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.04.001.

- Pickar JG. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002, 2:357-371. 10.1016/s1529-9430(02)00400-x