By the time we reach August, for many of us, those exciting early season races are a distant memory and our enthusiasm is waning. Tired legs make another month or two seem daunting, but whether it’s team commitments, a race you want to try, or simple stubbornness, you still want a little more time before you hang up the bike for the season.

But that’s not the way it has to be. Those late season months can actually be the most enjoyable part of the season. Joey Rosskopf, a pro rider with Q36.5 Pro Cycling and two-time U.S. National Time Trial champion sees late-season races as the reward after a season of hard work.

“I just feel more relaxed,” says Rosskopf. “You know where your fitness is at. It might not be good, but at least you know.”

Fortunately, extending your season doesn’t mean you have to keep slogging out more tough interval sessions. In fact, dogged dedication to the training routine may be what put you in the hole in the first place, says Rosskopf.

Managing fatigue

Houshang Amiri, head coach of the Pacific Cycling Centre and one of a few UCI World Cycling Center expert coaches, points out that to effectively manage fatigue, it’s critical that we first understand the different types of fatigue we can experience.

The fatigue we’re all most familiar with is acute fatigue. This is the tiredness you feel after a hard block or from staying out too late on a Friday night. This is not the fatigue we worry about. It’s when fatigue builds up over time without sufficient rest that it becomes chronic and turns into overreaching or overtraining. [1,2]

Those fatigues are mostly physical. There is another type of fatigue, called burnout, that comes from a loss of enthusiasm or sense of monotony that’s very common at the end of the season. “Usually if you see all those signs of fatigue,” says Amiri, “they come from unmotivated athletes. Keep the motivation level up and everything is going to work.”

Addressing fatigue is relatively easy—especially if it’s caught before it becomes chronic. The challenge is knowing what type of fatigue you’re experiencing so that you can choose the right solution. And that’s where it gets complicated.

Indicators of fatigue

Most training software can now track the balance between training stress and recovery, such as ATL and TSB in Training Peaks. And while Amiri feels these metrics are an easy guide for athletes, sometimes an athlete can be deep into an overreached state before it shows up on any graph.

Amiri finds one of the best early signs that an athlete is digging themselves into a hole is neuromuscular fatigue. A simple way to measure this is to look for a noticeable drop in 20-30 second all-out power compared to when the athlete is fresh. Supporting Amiri’s approach, a 1997 study out of the University of Ulm in Germany found that neuromuscular hypo-reactivity was an effective measure of overtraining. [3]

Another indicator of neurological fatigue is a depressed heart rate—meaning the athlete feels sluggish and it’s hard to hit normal values while training. Resting heart rate and heart rate variability can also be used to assess fatigue, but they are not clear-cut indicators. [4,5] A 2016 systematic review of overtraining measures in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found a low correlation between these metrics and chronic forms of fatigue such as overtraining. [6]

The review went on to show that subjective self-assessment—particularly disturbances in mood, perceived stress, and perceived recovery—tended to be a better indicator of fatigue than objective measures like resting heart rate. In other words, we intuitively know when we’re tired. This is why Amiri looks first and foremost to an athlete’s training journal, sleep patterns, and behavior to assess fatigue.

When fatigue becomes chronic

But even the subjective side is complicated. Acute fatigue (which is normal) and chronic training fatigue (which requires a change in your training) can feel the same and share many of the same symptoms. What differentiates them is that the more chronic forms of fatigue also see a drop in performance.

This is why training harder at the end of the season when your performance is waning may actually be the worst thing you can do. It will likely just dig you so deep into the hole that you won’t see light again this season.

Do the opposite—catch the fatigue early and take some good rest, and you may actually end up with the best legs you’ve had all season. A 2014 study in Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise had both acutely fatigued and overreached athletes perform a taper. The acutely fatigued experienced a large peak in form after two weeks of rest. The overreached group never saw their form fully return even after the rest. [7]

RELATED: The Key to Recovery? Take Care of Your Brain

Both Amiri and Rosskopf see the late season as a time to just maintain form, and according to Amiri, maintaining 90 to 95% is fairly easy to do. That said, Rosskopf recognizes that resting can be very hard for many athletes. When our form is dropping, the natural reaction is to train harder. “But that [resting] is something you should embrace,” says Rosskopf. “You can only do yourself a benefit to ride easy. I just sort of coast it out. Usually, I come [out] really good again. I let all the racing soak in.”

Tips to extend your season

The way to get a little more out of the legs is to carefully monitor fatigue, reduce the training load, and have some fun. Here’s some tips from our experts to do just that.

RESTQ or POMS on a weekly basis

Many studies use standard questionnaires to assess subjective fatigue and they are surprisingly accurate. Two validated and effective scoring systems are the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ) and the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Taking either one weekly can help track both chronic and acute fatigue.

Watch heart rate, resting heart rate, and heart rate variability

They aren’t perfect, but if you are seeing a consistently depressed heart rate, high waking heart rate, and lower-than-normal heart rate variability, there’s a good chance you’ve dug yourself into a hole.

Do some sprints

If you feel tired and are concerned it’s more than just acute fatigue, try a few 20-second sprints. If you can’t hit your normal numbers or if your legs are “burning” in a way that doesn’t feel normal, you may be overreached and need a big rest. Of course, it’s important you do a few sprints when you know you’re fresh so you have a baseline to compare to.

Take a longer rest if subjective fatigue is there AND performance drops

Acutely fatigued and overreached athletes both have the same subjective feelings of fatigue, but generally only the overreached demonstrate a consistent drop in performance.

Rosskopf says that if you’re tired from a weekend race or a late night of dancing, then a couple days of sleep may be all you need. But if you’re fatigued from a long season of training and racing, “then you need to stop digging a hole. Because if that’s the reason you’re tired, no hard training is going to make that better.”

If the numbers are still there, then a few days of recovery will have you back. If they aren’t there, a couple weeks of rest before continuing with your season may be appropriate.

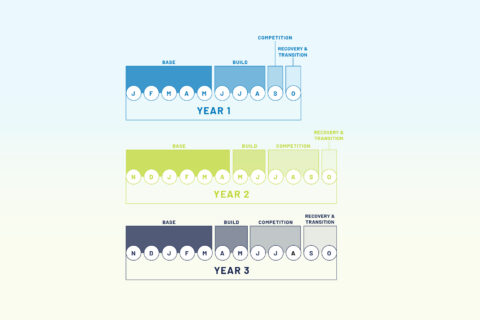

Plan ahead and have a recovery period built in

Amiri feels the best way to extend the season and deal with fatigue is to plan ahead. If you wait until you’re fatigued, there’s a lot you can do, but you’re still in reaction mode. Amiri recommends planning an active rest period of a week (or longer) once or twice through the season.

RELATED: How to Develop a Yearly Training Plan

Regularly adjust your training based on fatigue

“Your yearly training plan is a living plan,” says Amiri. Even if your entire season is mapped out, it has to be constantly adjusted based on your state of fatigue.

Build motivation by setting goals and changing it up

Much of the late season is about overcoming monotony and staleness. “You usually don’t see athletes complaining about fatigue if they are motivated,” says Amiri. Setting and believing in goals—such as an end-of-season race or PR—is internally motivating.

For external motivation, switching things up is sometimes all you need. Changing the training environment can also work wonders, according to Amiri, like trying new roads or a new training partner. Amiri likes to take his road cyclists to the track or put them on a mountain bike to do something new that still builds speed.

Train with races

Weekend races and weekday training races give you intensity without the monotony of intervals. Rosskopf really enjoys them because he can ride an hour or two easy on the other days. “I feel like I’m benefiting my performance if I’m doing a coffeeshop ride every day that I’m not racing.”

Back way down

It takes significantly less work to maintain your fitness as it takes to build it. In fact, a 2001 study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed just how little it takes. Trained cyclists reduced their volume and intensity 50% for 21 days. At the end of the period, they showed no drop in their performance. [8]

RELATED: How to Nail Your Next Taper

Rosskopf enjoys the end of season because it’s the time he can let nearly a year’s worth of training and racing settle in and simply ride it out. Just riding easy for three weeks may be enough to maintain fitness, especially if you do a few races. Get good rest, change it up with something different like track, and who knows, you may still have your best form of the year ahead of you.

References

[1] Kreher J. Diagnosis and prevention of overtraining syndrome: an opinion on education strategies. Open Access J Sports Medicine 2016;Volume 7:115–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajsm.s91657.

[2] Halson SL, Jeukendrup AE. Does Overtraining Exist?: An Analysis of Overreaching and Overtraining Research. Sports Med 2004;34:967–81. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434140-00003.

[3] Lehmann M, Baur S, Netzer N, Gastmann U. Monitoring high-intensity endurance training using neuromuscular excitability to recognize overtraining. Eur J Appl Physiol O 1997;76:187–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004210050233.

[4] Hebisz RG, Hebisz P, Zatoń MW. Heart Rate Variability After Sprint Interval Training in Cyclists and Implications for Assessing Physical Fatigue. J Strength Cond Res 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000003549.

[5] Acharya UR, Joseph KP, Kannathal N, Lim CM, Suri JS. Heart rate variability: a review. Medical Biological Eng Comput 2006;44:1031–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-006-0119-0.

[6] Saw AE, Main LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring the athlete training response: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: a systematic review. Brit J Sport Med 2016;50:281. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094758.

[7] AUBRY Anaë, HAUSSWIRTH C, LOUIS J, COUTTS AJ, MEUR YL. Functional Overreaching: The Key to Peak Performance during the Taper? Medicine Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1769–77. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000000301.

[8] Rietjens GJWM, Keizer HA, Kuipers H, Saris WHM. A reduction in training volume and intensity for 21 days does not impair performance in cyclists. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:431. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.35.6.431.