The goal belongs to the athlete—not the coach. It’s the coach’s job to help the athlete give shape to the final product.

The goal belongs to the athlete—not the coach. It’s the coach’s job to help the athlete give shape to the final product.

The goal belongs to the athlete—not the coach. It’s the coach’s job to help the athlete give shape to the final product.

The goal belongs to the athlete—not the coach. It’s the coach’s job to help the athlete give shape to the final product.

We explore what it takes to develop from a recreational triathlete into an IRONMAN World Championship qualifier.

Finding another month or two in the legs may be more about careful management of fatigue and having a little more fun.

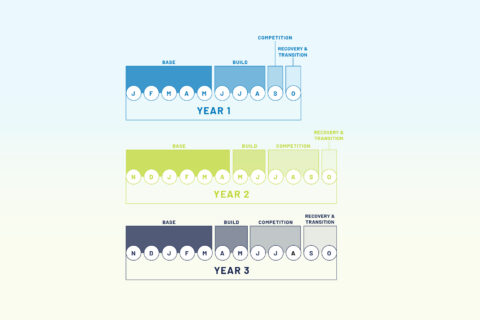

If you’re looking to tackle some ultra-endurance events it’s important to take a longer-term approach to your training that extends beyond a single season. We explain how and why.

Goals are best evaluated in the rearview mirror. Joe Friel reflects on the goals of three endurance athletes, highlighting lessons learned.