What should a female athlete do when confronted with the choice of adjusting her training (or racing) around her menstrual cycle, or pushing through the symptoms and hoping for the best? And are those the only two choices?

Some coaches and physiologists contend that we should let the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle dictate the training plan, and that the plan should be built around the favorable and less favorable hormones.

Ruth Winder, the current U.S. national road champion and member of the Trek-Segafredo WorldTour team, said that while she usually suffers from cramps, bloating, fatigue, and difficulty focusing during her menstrual cycle, she doesn’t employ specific strategies to deal with them.

“I normally just embrace the suffering,” Winder said.

Recently, though, there has been an injection of new research that helps us better understand a woman’s unique physiology. These new findings can better equip Winder and other female athletes with more sophisticated options than just suffering through it.

Two strategies: suffer through or take control

In my experience as a coach, I recommend education as the first-line of defense against the effects of the menstrual cycle. Empowering the athlete with a better understanding of why she experiences certain things during her cycle can provide tools that help her to be proactive in mitigating the unfavorable parts and capitalizing on the more favorable phase of the cycle.

“With so many variables and so much variance in one athlete’s cycle month to month, training and racing around a menstrual cycle may be complicated, unrealistic, and take away focus from other aspects of athletic development and performance,” said Dr. Dana Lis, a Ph.D. and high-performance dietician who works with WorldTour cycling teams.

There is also a mental challenge to these two approaches to contending with the cycle. In the first approach—adjusting to fluctuations—the athlete lets the cycle dictate her schedule, and she plans training and racing around it. In essence, the cycle controls the athlete.

Employing the second approach, the athlete takes control, and empowers herself with education and information. This places the athlete in the driver’s seat and instills confidence that she has the tools to effectively deal with the circumstances of the cycle.

Furthermore, a competitive athlete does not always have control over the race calendar. Thus, when she’s in control, she can be proactive and develop strategies to contend with the sometimes-challenging effects of the menstrual cycle.

RELATED: Separating Fact from Fiction for Female Athletes—with Dr. Stacy Sims

Science isn’t sure, but coaching has answers

Historically, most physiology research has been conducted on men. As a result, a significant majority of the training methodology has been based on male physiology.

Due to the complexity of the menstrual cycle’s effects on performance and physiology, and the relatively few studies that have been conducted on female athletes, research is inconclusive regarding how best to contend with the menstrual cycle in athletes.

For several reasons, however, including an increase in women’s participation in sport and a lack of women’s-specific training methodologies, there has been a surge in interest in research to better understand women’s physiology.

The complexity around women’s physiology is primarily driven by those hormonal fluctuations and, in some cases, contraceptive use. Additionally, what is considered a normal menstrual cycle is in fact a unicorn.

“I have measured massive variance in cycle duration and hormones within the same athlete month to month and from athlete to athlete,” Dr. Lis said.

Recent research suggests that 50% of exercising adult females and 54% of exercising adolescent females experience menstrual dysfunction, or irregular cycles. [1]

Your hormone cycle: a reminder for women and men

The biggest difference between men and women are the circulating hormones. In men, the primary hormone is testosterone, and in women it’s estrogen and progesterone. In terms of athletic performance, these hormones primarily affect muscle strength and fuel utilization.

While most women know this, here is a quick refresher for male coaches who coach females on what is happening hormonally during the menstrual cycle.

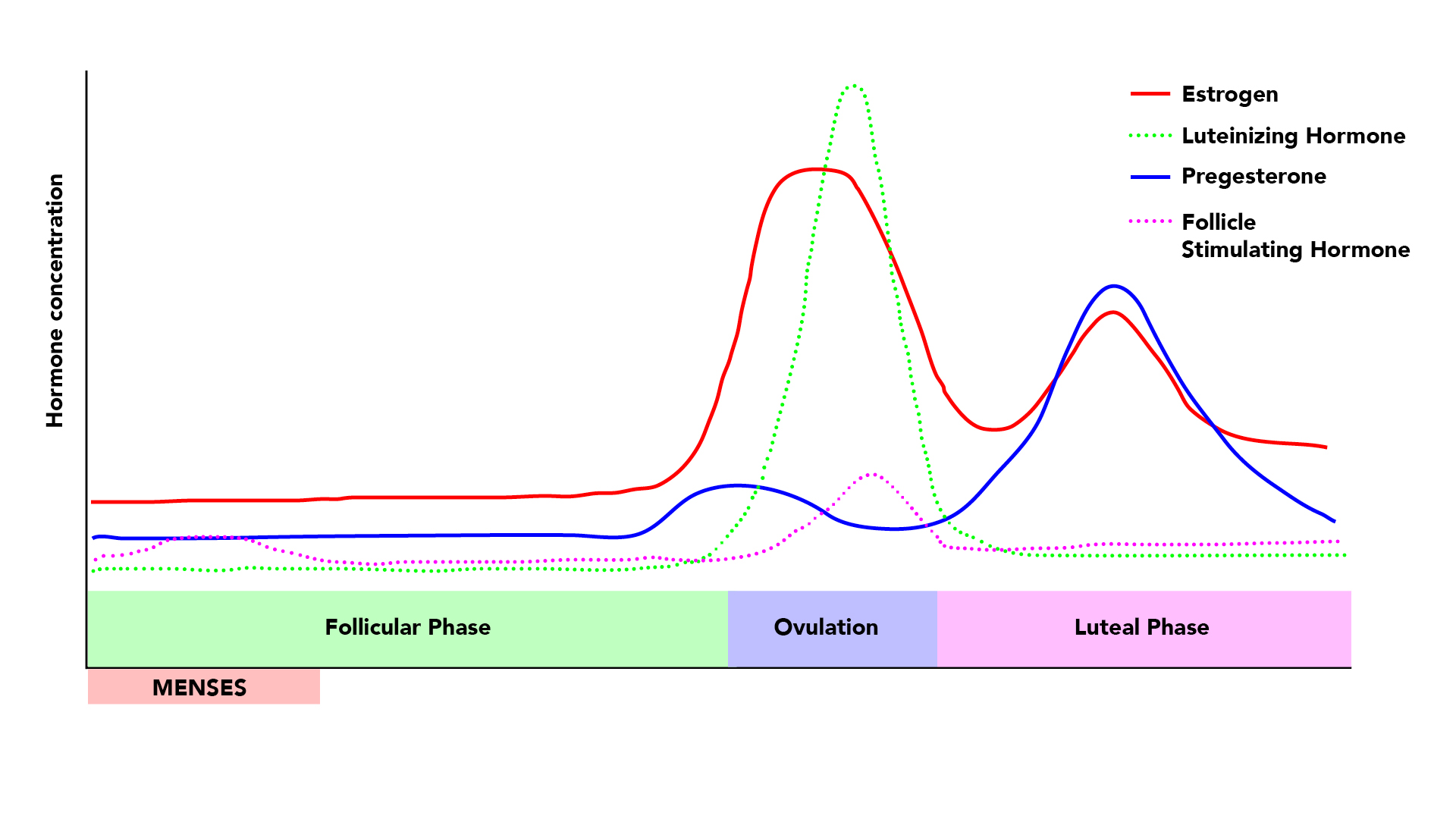

The menstrual cycle comprises three phases:

- Follicular: generally occurs on days 1-14

- Menses: menstruation, a.k.a. the period, which generally occurs on days 2-7 during the follicular phase

- Luteal: generally occurs on days 15-28

Estrogen levels are low during menses; they are relatively high during the follicular phase, and spike toward the end of this phase; and they are moderate during the luteal phase. Progesterone, on the other hand, remains low during menses and the follicular phase, and skyrockets in the luteal phase.

However, regardless of the complexity and inconclusive research findings, there are proactive measures female athletes can take now.

Step one involves encouraging the athlete to get to know herself, and to avoid generalizations on what she should expect and how she should feel during her cycle. This is easy to do: The athlete tracks and monitors her menstrual cycle, and includes subjective comments on how she feels.

This will help her learn about her individual physiological responses and feelings throughout her cycle. Knowing what to expect helps reduce the stress and anxiety, and also develops confidence.

Adjust your diet, change your hormones

Now we can detail the main issues that athletes confront, and some dietary strategies to help lessen those effects, courtesy of Dr. Lis.

However, keep in mind that what is most important is that the athlete tracks and monitors how she feels during the month, and does not let generalization cloud her experience.

Change foods to reduce bloating

- Five to seven days before menstruation begins, increase protein and potassium-rich foods (vegetables are our best sources.) Also, consider supplementing magnesium intake and omega-3 fatty acids. While we generally don’t recommend regular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug intake, if the pain becomes unmanageable, ingesting 80 milligrams of aspirin will inhibit prostaglandins.

- Use dietary strategies to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms. For example, consume low residue foods, such as well-cooked vegetables, fresh fruits such as bananas and cantaloupe, and eggs. If you’ll be racing, reduce gas-producing foods like Brussels sprouts, and reduce high FODMAP* foods such as garlic, onion, and wheat, which may be triggers for you. [3] Avoid too much unnecessary dietary restriction, however.

*FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols, which are short chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols that are poorly absorbed by the body, resulting in abdominal pain and bloating.

Reduce headaches

- Maintain euhydration (normal hydration levels).

- Include foods high in nitric oxide in your diet, including beets, beetroot juice, and rhubarb. That said, beets are a known trigger for migraines in women, so experiment.

Monitor fatigue and mood

- Reduce training duration, and stick with shorter, harder efforts versus longer threshold-type efforts.

- Be mindful to get your daily required intake of branched chain amino acids (BCAAs), especially leucine, which can help reduce effects of serotonin.

Training changes can help

Now let’s address how to facilitate the best training adaptations despite the possible negative hormonal impact.

Impaired fuel utilization

Estrogen stores glycogen and promotes fat oxidation, which in some ways might sound great. However, glycogen is needed to fuel high-intensity work. Because of this, it is particularly important to ensure adequate carbohydrate intake, especially when estrogen is high and high-intensity workouts are prescribed in the training plan.

Thus, during times of high estrogen, you should increase carbohydrate intake, particularly before racing and intense workouts.

Boost protein to repair hormonal muscle damage

Progesterone has a catabolic effect on muscles, meaning that this hormone breaks down muscle mass. In addition, it is believed that women, due to lower carbohydrate oxidation, also demonstrate lower amino acid oxidation. [2]

These factors result in greater muscle breakdown during intense efforts. Leucine is a key player in muscle repair and building. While natural sources are always best, whey protein is also good source of this BCAA.

While Dr. Lis makes certain that her athletes are always meeting optimal protein and leucine levels, it is especially crucial during the luteal phase. Be especially mindful to replace leucine within 30 minutes after an intense workout, or strength workout.

Boost sodium to increase blood volume

Both estrogen and progesterone trigger hormones that, through a series of mechanisms, reduce plasma volume. For example, estrogen increases the hormone vasopressin, which acts to retain water and vasoconstrict blood vessels. As a result, blood pressure rises, which in turn triggers a drop in plasma volume in order to reduce the demand on the heart.

Progesterone acts in a way that blocks aldosterone, a hormone responsible for sodium retention. Water follows sodium. With less aldosterone released and present, there is a reduction in water retention resulting in a further reduction of the plasma volume.

Thus, it is recommended that female athletes pre-load with sodium-containing fluids—found in many electrolyte drinks.

RELATED: How the Menstrual Cycle Can Work to the Athlete’s Advantage

Train hardest (or race) during luteal phase

From the day a female athlete’s period starts, through approximately the next 14 days, her physiology mirrors that of a male’s physiology. During this phase, energy systems consumed by the high-hormone luteal phase are freed up for use.

Some studies suggest that this is an ideal time to make strength gains and produce big power numbers. Additionally, studies indicate that during this phase, the athlete will feel less pain and recover better.

Ultimately, there is more research to be done. In some ways, the jury is still out if the female athlete should train according to her cycle. Rather than fret about those adjustments, she should focus on where she can make her biggest gains.

Track, but don’t obsess over the menstrual cycle. Empower yourself as a female athlete (or coach of a female athlete) with knowledge and proactive strategies to mitigate less favorable effects of the menstrual cycle, and be equipped and confident to deal with any situation.

References

- Pitchers, G. & Elliott-Sale, K. (2019). Considerations for coaches training female athletes. Professional Strength and Conditioning, 55:19-30. Retrieved from https://www.uksca.org.uk/assets/pdfs/UkscaIqPdfs/considerations-for-coaches-training-female-athletes-637139103922340876.pdf

- Tarnopolsky, M & Ruby, B. (2001). Sex differences in carbohydrate metabolism. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 4(6):521-6. Doi: 10.1097/00075197-200111000-00010. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11649202_Sex_differences_in_carbohydrate_metabolism

- Lis, Dana. (2019). Exit gluten-free and enter low FODMAPs: A novel dietary strategy to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms in athletes. Sports Medicine, 49: (suppl 1): S87-S97. Doi 10.1007/s40279-018-01034-0. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6445805/