Last year, on the morning of an event, Coach Connor was asked to step in and be a corner marshal. The next thing he knew, he was jumping into action to help an athlete lying on the side of the course experiencing a heart attack. No matter if you’re a race organizer, a volunteer, or another athlete at an event, it’s more than likely you’ll come up on an incident where someone is hurt and needs support or even medical intervention. So, here’s the important question: what’s your role, and do you know what to do when the time comes?

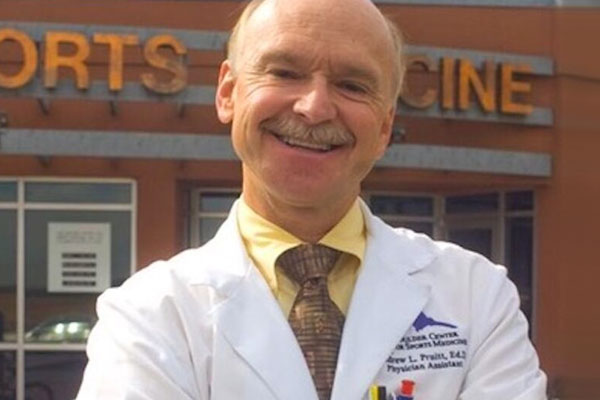

On today’s episode, we talk with Dr. Andy Pruitt about the ins and outs of providing support from the greater infrastructural and logistics perspective all the way down to the individual event volunteer or race participant. There may be no one out there who understands medical support at events as well as Dr. Pruitt does. He invented the Rolling Medical Enclosure for the Tour duPont and the 1996 Olympics, and it was so well regarded that it then became the standard for The Tour de France. The whole purpose was to ensure that medical support was always as close to a potential incident as possible, because minutes can – and have, saved lives.

First, we dive into the history of medical support at professional events and how certain lessons learned were the catalyst for much-needed improvements, and what we see at major events today. Shifting gears, we talk about challenges faced and improvements that can be made at the local level. Local event promoters often don’t have the budget for a rolling enclosure. So, what can they do to make sure their event is prepared for any incident? Because that’s the only guarantee – incidents are going to happen at some point.

Then we wrap up with individual roles and responsibilities. Not everyone is a doctor, nurse, or EMT, and no one should be intervening in a way that is beyond their scope or could also put themselves in danger. But that also doesn’t mean there’s nothing you can do. In fact, the quick action of the volunteer can be pivotal. Dr. Pruitt shares what you can do as either a volunteer or a race participant, and how the changing culture of endurance sports has led to somewhat of an increased participation of the latter. Two of the takeaways here are to make sure you have your own medical bag and take a basic CPR course every couple of years. Basic CPR can be the difference between someone living and dying. We all need to be ready. We hope this episode helps prepare you.

So, pack up your Tegaderm, and let’s make you fast!

Episode Transcript

Griffin McMath 00:04

Hello and welcome to Fast Talk, your source for the science of endurance performance. I’m your host, Dr. Griffin McMath here with coach Conner. Last year on the morning of an event, coach Connor was asked to step in and be a corner martial. The next thing he knew he was jumping into action to help an athlete lying on the side of the course experiencing a heart attack. No matter if you’re a race organizer, a volunteer or another athlete at an event, it’s more than likely you’ll come upon an incident where someone is hurt and needing support, or even medical intervention. So here’s the important question. What’s your role? And do you know what to do when the time comes? On today’s episode, we talked with Dr. Andy Pruitt about the ins and outs of providing support from the greater infrastructural and logistics perspective, all the way down to the individual event. Volunteer or race participant, there may be no one out there who understands medical support at endurance events as well as Dr. Pruitt does. He invented the rolling medical enclosure for the Tour DuPont in the 1996 Olympics. And it was so well regarded that it then became the standard for the Tour de France. The whole purpose was to ensure that medical support was always as close to a potential incident as possible, because minutes can and have saved lives. First, we dive into the history of medical support at professional events, and how certain lessons learned became the catalyst for much needed improvements and what we see at major events today. Shifting gears we talk about challenges faced and improvements that can be made at the local level. Local event promoters often don’t have the budget for a rolling enclosure. So what can they do to make sure their event is prepared for any incident because that’s the only guarantee incidents are going to happen at some point, then we wrap up with individual roles and responsibilities. Not everyone is a doctor, nurse EMT, and no one should be intervening in a way that is beyond their scope, or could put themselves in danger too. But that also doesn’t mean there’s nothing you can do. In fact, the quick action of the volunteer can be pivotal. Dr. Pruitt shares what you can do as either a volunteer or race participant, and how the changing culture of endurance sports has actually led to somewhat of an increased participation of the ladder to the takeaways here to make sure you have your own medical bag. And to take a basic CPR course every couple years. basic CPR can be the difference between someone living and dying. We all need to be ready. We hope this episode helps prepare you. So pack up your Tegaderm and let’s make you fast.

Trevor Connor 02:30

Well, welcome Dr. Pruitt. Great to have you back on the show.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 02:33

It’s been a little bit. Always my pleasure. Glad to be here.

Trevor Connor 02:36

These are always fun conversations. We go to a different place with you. And I think we’re gonna go somewhere we haven’t gone before. But I think it’s gonna be really interesting, which is talking about medical support, and what happens when the inevitable happens at events? Did that make sense?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 02:56

Well, it makes sense from lots of different people’s perspective, right? The race promoter, the rider, and the medical support for those events. But most crashes don’t happen at events. Most crashes happen while training.

Trevor Connor 03:10

And I was mostly getting on the fact that I think I just used horrible grammar. So that’s where we’re starting out today. Griffin’s like, “I can ask the intelligent questions,” and I’m like, “Damn it, I’m gonna ask the dumb questions,” but I have started.

Griffin McMath 03:23

I think what the whole purpose of this episode too is Murphy’s Law. It’s bound to happen. So at least when it does happen, you’re gonna know what to do and how to handle the situation from the vantage point of what role you play in that moment.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 03:36

There’s a saying out there that I’ve known for 40 years. You’re not a real bike racer, unless you’ve broken a collarbone. Some of us are double dipped even, in that sense.

Trevor Connor 03:45

Second race ever.

Ryan Kohler 03:51

Pathways from Fast Talk Laboratories are a new way to explore concepts, master skills and solve training challenges. Our new cycling interval training pathway begins with the basics of interval workouts and progresses to more advanced details. How to flawlessly execute interval workouts, which intervals bring which adaptations, and how to analyze your interval workout performance. Over 21 articles, interviews, workshops and workouts. Our new cycling interval training pathway offers you the chance to master cycling’s most critical and nuanced workout format. See this pathway at fasttalklabs.com.

Unexpected Situations

Trevor Connor 04:36

So here’s the thing, though, we’re going to be talking a lot about events. And some people listening to this might go, “Why do I care about this?” You might not participate in events or you’re thinking we’re just talking about races, but that’s not the case. Things happen at Gran Fondos. Things happen at the local group ride that you get together for. And even though you might be somebody who’s mostly on the bike participating in the event, eventually all of us end up in that other place. And I’m going to share a quick example of this. I was in Ithaca, New York last summer, staying with some friends,. And I was about to go out for my long ride. And my friend said, “Hey, Trevor, can we ask you a favor?” I’m like, “Sure.” He’s like, “We got the Empire State senior games going on today, would you come and stand on a corner?” so I’m like, “Sure, I’ll show up.” So I plan my ride, then ride out to where they were having the event. I’d stand on the corner and then finish my ride. So I got there, they put me on a corner, I’m standing in full kit trying to be a corner Marshal. And as the field is coming towards my corner, one of the guys crashes. He had a heart attack. Sadly, we got the ambulance there, got him in the ambulance, but they didn’t get into the hospital in time. And he didn’t make it. So it was a really sad event. But here I was, just going out for a ride. Next thing I know I’m dealing with trying to save somebody’s life. So you never know when you’re going to be in this situation.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 06:05

Great story. Questions. Were you in any way basically medically trained? Number one. Number two, did you perform any medical procedures, CPR, etc? Were you armed with radio to call the ambulance? So for my mind, my covering so many events and racing some events, where is the ambulance? So a follow up on that story.

Trevor Connor 06:28

Yeah, I’ll give you the the details. I didn’t see the crash. The corner I was standing at, if you look back on the course, there was a hill that blocked your view. So we were sitting there on the corner going, “Why hasn’t the field arrived?” We knew what the timing should be, and eventually went, “Okay, something’s not right here.” We walk to the top of the hill. And that’s when we saw something’s going on there. We were trying to communicate back to the organizers at the start of the course, “Hey, something has happened.” They have all the different fields on the course at the same time. So even though they had an ambulance that was out there following this, it wasn’t right behind. So there wasn’t an immediate response. So we knew we need to get the ambulance there. To answer your question, yes, I did take my certification when I was at CSU. But that was over 10 years ago. So I don’t fully trust my knowledge. I’m going to do what I can do. But I’m mostly going to try very quickly to get the professionals there to deal with it.

Griffin McMath 07:27

I’d say too, what’s the certification? Because I think one of the things that we’re going to eliminate in this episode is what type of medical knowledge one should be prepared for. Right?

Trevor Connor 07:37

Right. And what I would say is I am not an EMT, nor do I play one on TV.

Griffin McMath 07:42

Was it a basic first aid certification or like a CPR certification?

Trevor Connor 07:46

Yeah, I just got the basics.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 07:47

Which can save lives. Even bad CPR can save lives. So I don’t want us to get a sidebar going here really early. But this is just some of the things we want to talk about.

Griffin McMath 07:56

We’re going straight for it, Andy.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 07:59

So yeah, even bad CPR can save a life. So COVID got people afraid of mouth to mouth, of course. But just basic chest compressions can save a life because you’re moving air with the chest compressions. So anyway, I know this is an early sidebar, we’ve gotten off on a tangent already. Apologize. But the story is a great story. And a great example of you standing there in your cleats scittling around trying to save this guy’s life. And it happens at every race, especially local races.

Trevor Connor 08:27

And I can tell you what went through my head. I think this is the important side, that would be very different from what would go through your head. As I saw this, and the first thought was, “Oh, crap, what do I do?” Where you would have seen this and probably just immediately been into action and knowing what to do. And that can make a difference.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 08:48

Yeah, one can hope that whoever’s on that corner might know what to do, or at least be armed with the radio. Right? That was my question. How were you in contact with the race promoter?

Trevor Connor 08:57

See, they didn’t give us radios. We had phones. So I’m trying to call people. We got the ambulance there. And like I said, they tried to get him to a hospital. What they said was he was probably either dead or close to dead before he hit the road. There was just nothing we could have done.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 09:15

It’s one of the shortcomings of being a local race promoter. And I sure don’t want to throw them under the bus because we need them. The highest cost of a local race promoter is police protection. The number one cost. That’s what puts major races out of business is police protection. Number two, is hiring medical staff. And they go with the minimums. They hire an ambulance that sits at the corner, sits at the start finish line. Rarely is it a mobile ambulance, and if it is, it’s never gonna be in the right place at the right time. So we’re going to talk I think, ultimately about how professional race is covered, should be covered. But really, it’s sad that it is such an expense to local race promoters, when it’s as important as the police protection. But not required, like the police protection. A basic ambulance is required. That’s it.

Trevor Connor 10:01

Thank you for getting us back on the outline here. So let’s go there because you have been a part of this. Medical support at professional races has changed pretty dramatically in the last 40 years. And I know you are a big part of that. So let’s start with what was it like 40 years ago? And what improvements, what changes have they made?

Medical Support and it’s Growth

Dr. Andy Pruitt 10:22

So I, like most people my age in their 60s and 70s, were really brought to the sport by the Red Zinger and the Coors Classic back in the 70s. So I was then the athletic trainer at the University of Colorado, and a young biker. A younger bike racer. And had a loose affiliation with the race, mostly with direct teams taking care of Connie Carpenter and Davis Finney and their teams because we were friends, local racers. And it hit me early on that this really well meaning race medical director was a local nurse. He had good volunteer doctors, etc, etc. Had a good ambulance. He had a good post race clinic. But there was really not much on the road, right? It was the typical ambulance following the peloton. Now those kinds of pressure races there’s only one category on the road, not multiple categories, right? Just the man or just the women. So he had a follow ambulance. And if you watch the Tour de France in those days, and there was a crash, it took 20 or 30 minutes sometimes for the ambulance to get to the crash. And it was the mentality in those days to get back on. First question you asked when you hit the ground is “Is my bike okay?” And you get back on your bike and you go. So concussions were not assessed. Fractures were not assessed. That was so you got back on your bike. So my career began as an athletic trainer. And for those listening who might not know what an athletic trainer is, it’s not the guy at the health club helping you lift weights. It’s the person or persons that run out on the field during an injury on a football game or a basketball game. And they’re the truest form of sports medicine. The only people who practice sports medicine, full time job is an athletic trainer at the high school, college, or professional level. So my mindset, the number one thing athletic trainers think about, is a safe playing field, right? So I would examine football fields. I would examine basketball courts. I examined tracks. That was part of my job. And then I was asked to start covering bike races. I get on the back of a motorcycle and I would ride the course at race speed and identify the telephone poles and potholes and all those things that were going to become a danger because this is the trajectory of a bike at this speed. So I began to look at bike races like football game. Like a basketball game. What happens when it’s a point to point 200 mile road race? Never going to be in the right place at the right time. So make a long story short, I was invited to be the Chief Medical Officer for the Tour de Pont. Which began as the Tour de Trump and then ultimately became the Tour de Pont. Which was next to the Tour of California, maybe even better than Tour California That kind of European stage race on American grounds. I was asked to be their medical director. So I went to them with a budget. And here’s one of the very first changes that had to occur. They were not accustomed to paying for medical support. It was a volunteer basis. They said “Well, the US ski team, those doc’s volunteer.” No they don’t. So I gave them a budget and it was for three doctors, two nurses and physical therapists and athletic trainer. Everybody got a salary. I needed two motorcycles and I said two motorcycles. I need a follow car, a motorhome and a local ambulance because we’re passing through multiple hospital districts, not just one, right. You can see the local police hand off as we change the county line. And the ambulances would trade off as we crossed into another district. So I built what was then called the rolling medical enclosure. The officials in those races have a rolling official enclosure. There’s a head car, middle car trailing car. The ambulance used to be behind all the team vehicles. So I wanted a motorcycle that went with the lead group. Whoever the breakaway was, that was me. The second motorcycle stayed with the main peloton. And there was a lot of radio communication to make sure that the primary contestants were covered. The medical car stayed with the gruppetto, or the slower of the group on the road. The motorhome leaped over the race and went to the finish city. We had a start line clinic. We had a finish line clinic. And then a suite in the hotel. But the real key here is the rolling medical enclosure. We save lives. The very first year there was a young Colombian kid who caught his ear on the side of a speed limit sign and ripped his ear off. I was on him almost by the time he hit the ground. He’d swallowed his tongue. And if you’ve ever wondered why there’s a thing in a first aid kit called an oral screw, it’s to pry open lock jaw. And you break teeth. You stick this thing in there and you screw their jaw open. And I pulled out his tongue. And by that time my follow car had gotten there. He was an ER doc and said “He’s all yours, Prentice. Bye bye.” And so we could catapult and take care of these people. So quickly. And we save lives. The next one, next year. You think, time tria. Safest thing on earth. No, the worst accidents happen in time trials, because they’re not looking down the road. And one of our young Americans actually had his head down and ran into a post in front of what is now the Trump Tower in Atlantic City. He took the shortest line between two points and had his head down and ran into a post. I happened to be on that one as well. My point is, is that the rolling medical closure was something entirely new. Entirely new. MetalSports owned and ran those races. They ran all the big races, Georgia, Georgia, Georgia, California Raba. And they adopted it. They saw the need. They paid the budget. They paid us all and they adopted that race philosophy. The word got out. Other races started to at least have medically trained people on dangerous corners, A roving medical car plus a stationary ambulance for cleanup at the start finish lines. I had the honor of being the Chief Medical Officer for USA Cycling from 92 to 96, which ended with the Atlanta Olympics. So I had dual credentials in Atlanta. I was the chief medical officer USA Cycling, and the Chief Medical Officer for all the cycling venues in Atlanta. I was changing clothes a lot because you can’t represent the United States if you’re going to take care of the whole venue. But the Tour de France owners and race promoters came to watch the Olympics, obviously, because it was the first time pros raced in the Olympics in 96. And A.S.O, the owner of the Tour de France then adopted the rolling medical enclosure. They used motorcycles early on. I think some of the old doctors that cover the tour weren’t exactly comfortable on the back of a motorcycle. I can tell you a lot of fun motorcycle wound care stories. If we have time, they’re really awesome. But now you see them holding on to a convertible. So the the Tour de France now uses several convertibles in the race instead of motorcycles. I did see last week Tour Lombardi, I think it was, they actually had medical motors. So my point is the rolling medical enclosure is now the standard. It was born in America, born at the Atlanta Olympics, and is now the standard for professional road racing.

Griffin McMath 17:40

Wow.

Trevor Connor 17:41

Fantastic. Yeah, I’m sure you have great stories.

Griffin McMath 17:44

Yeah. Some would call great. Someone would call gross.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 17:46

No, no, no. So a guy had crashed. And my driver was a guy named Bruce Gottlieb. He is a PhD psychologist, what a concentration this guy could have. And a guy had crashed, we’ve gotten him back up and we were rolling. As long as they’re holding on to the medical motor, you can advance them back to their original place in the race. So he’s hanging on to Bruce’s shoulder. We’re going down a descent through the Allegheny Mountains, high speed, and I’m scrubbing a wound and putting burn netting on his knee. We get to the flat, we’ve taken him back up the race. His wounds all dressed. I say, “Ah, Bruce that was great.” And he goes, “I’m shaken.” I said, “Why?” He goes, “I’ve never done that before.” Here’s my driver that has all this competence, that took us down this high speed descent with a rider holding on to his shoulder and I’m leaning off the bike scrubbing a wound.

Trevor Connor 18:41

Here’s how I know you have a lot of field experience. Because a couple years ago, you showed me this horrific picture of a bone break. I was – I’m not a queasy guy, and I was sitting there kind of trying to hold it in. You’re like, “Isn’t this cool?”

Dr. Andy Pruitt 18:58

I know that was either Taylor Phinney’s compound fracture or Chloe Dygert’s compound fracture always.

Trevor Connor 19:06

You said “This is Chloe’s leg,” and I was just looking at going, “That’s a leg?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 19:09

Who was on the podium yesterday. In Europe. So persevere.

Trevor Connor 19:13

Do you remember the mechanic that we had for Team Rio Grande? Alex? Alex had done two tours of duty in Afghanistan as a medic. So he has seen everything. If you remember there was that huge crash at Hilo where like 70 riders went down in high speed descent. Race managers were trying to walk through it and like getting sick from looking at all the carnage. I just remember Alex walking right through the middle of it stopping looking down and going. Ooh, a finger. And he kept walking.

Griffin McMath 19:47

So I think you covered a few different races, a few different approaches to setting something up. And something very obvious is the evolution of safety precautions, medical support. I would imagine often happens from unfortunate lessons learned. Not really great foresight. Also we learn from mistakes and from decisions that it was like, “Oh, that was maybe a great thought, didn’t work.” Or no one thought of this. Can you think of maybe some major catalysts for improvement that came from big lessons learned, or maybe even some failures?

Improvements and Failures

Dr. Andy Pruitt 20:22

Oh, there were deaths on the road and catastrophic injuries on the road where the medical care was so late to get there. Even the Tour California. There was one where it was a significant head injury. His team put him back on his bike, and he looked like a wobble not going down the road. It was obvious that he was incapable. And ultimately, the medical coverage got to him, got him off his bike and took him out of the race. But historically, that was pretty common. The team would just get him back up on their bike. We got to hurry because the medical guys are coming, they’ve got to pull him out of the race. So by having more medical support guys that are living in their moving peloton, the teams get to know these guys. We’re knocking on the windows, we’re talking, we’re sharing lunches we’re rolling along. They suddenly go “Oh man, okay, I feel much better because he’s here.” But it was those significant injuries and deaths that occurred because the ambulance was too far back.

Griffin McMath 21:16

So that’s one of the biggest takeaways I’m already getting from this, is it’s about timing. And if anything, it almost doesn’t even necessarily matter who’s the first person to get to you. You called the story of the ER doc. The ER doc wasn’t the first one on the scene for that. It was you, and at least something started. And then you were able to pass off and move forward so that the rest of who you were with you could attend to. So this kind of earliest intervention possible, and the accessibility of the medical support to the actual athletes. And then their ability to leave really sounds like one of the biggest themes.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 21:51

Sadly, it’s a really expensive endeavor to do it correctly. That’s the problem. If we go now to a more basic race, they have roving, medical motorcycles all over the course. The course is only nine miles long. So those guys are on the roll all the time, and they’re in radio contact with each other. And with the marshals. That’s the key, right? Even though I was right there behind this one particular crash, most of the time you’re never going to be in the right place at the right time. It’s about getting there with expediency.

Trevor Connor 22:23

So taking this whole concept of the rolling enclosure, and you’ve already started to answer this, how does a local organizer apply this to a local race? I’m particularly thinking now of gravel races where access is tough.

Rolling Enclosures

Dr. Andy Pruitt 22:36

So let’s take Unbound, for example. 200 mile Unbound race. They will tell you that you’re on your own out there, and that you probably are not going to be extricated from the course if you have a mechanical or a medical injury. The Kansas City four wheel drive club is who they depend on to be all over the course. Because that course does require four wheel drive. So it’s harder. These extreme gravel races and even endurance mountain bike races do really challenge the guy who’s in charge of medical care, no doubt. So multiple placements along the course. Remember, I said I used to drive the motorcycle and look for the trajectory of the crash. Where’s this rider gonna land when he slides out on this corner? We used to place first aid stations on those corners. Just like self service, they would slide right into the tent. If you plan it right, they just crash right in your lap. But that’s a criterium or circuit race where you can up plan that. The medical care for these extreme outdoor events is really difficult. It’s really difficult. It’s really about crucial placement, periodical placement, crucial location and radio contact initially. And then it has to do with the first aid. What do they have in their Jeep, right? There’s got to be a wound care, there’s got to be ability to do CPR, there’s got to be a neck collar. There’s got to be some really basic things even out there in the wilderness to perform first aid.

Griffin McMath 24:09

I love that there’s a secret hero to this, and it’s physics. Where’s the body gonna fling? Those physics prereqs are really coming in handy for those instances.

Trevor Connor 24:19

So if I was organizing an event, let’s say GranFondo. So it’s not just racing. GranFondo, you’ll have some race in it, but you have a lot of people that are just participating. And I came to you and said, “I need to do some sort of medical support at this event. I don’t have a big budget.” What would be your recommendations to me? What would be the things I would need to do?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 24:40

What a great question. Find a medical sponsor.

Trevor Connor 24:44

By the way, you heard that? I have the smart questions today.

Griffin McMath 24:49

We’re taking tally’s.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 24:52

I’m not gonna give a dumb answer. I’m trying not to anyway. Find a medical sponsor. So many, many orthopedic offices now are are wanting to attract a sports medicine crowd. And they’re willing to provide either a budget and or physicians, athletic trainers that they employ to cover those events. When I got out of the event coverage business – Tour California, for example, they went to a large hospital chain. And the large hospital chain came in as a sponsor of the race. And part of that sponsorship was providing the rolling enclosure, the vehicles, the staff, all those things. If it’s a local event, and you can’t attract physician office or a local hospital, there are now freelance event first aid companies. That you can hire and they arrive in what’s typically a van or sometimes in an ambulance that’s been retired that they’ve not converted to their rolling first aid station. And they provide usually an EMT, which is the most common race coverage at this point locally is our EMTs, or athletic trainers. So you’ve got to find somebody who’s willing to take that responsibility. And understand the sport, understand the course and have appropriate first aid. I’m not gonna say certifications. I’m gonna say skills.

Griffin McMath 26:09

What do you think the budget ranges from a local race to the Olympics for medical support like this?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 26:15

For a local race promoter to spend $1,000 for a full day, that’s stretching their budget.

Trevor Connor 26:24

They have no money.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 26:26

Local race promoters are angels for the sport. They’re really not in it to make money. The police coverage is required. And that is the number one expense. So yeah, I think you can probably get an ambulance and two EMTs for 500 bucks, which is going to be your minimal coverage for a day long event.

Trevor Connor 26:48

But as you pointed out, if you have hundreds of people out there on the course, at all different points on the course ability to cover that –

Griffin McMath 26:55

And your estimate was like 500 bucks, and I’m like that’s not enough. Like there’s no way.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 27:00

Oh, no. Medical coverage, it’s expensive to do it right. And therefore, still even today, knowing what we know is typically not done right.

Ryan Kohler 27:13

The more you measure training data, the more important understanding it becomes.

Trevor Connor 27:17

In our advanced performance data analysis pathway, we move beyond the basics to explore more complex data analysis. We help you navigate complex techniques so you don’t get lost in the numbers.

Ryan Kohler 27:27

This pathway features Tim Cusick, Dirk Friel, Armando Mastrogy, Dean Gulledge, Joe Dombrowski, Trevor Connor, Dr. Steven Shown, and me Ryan Kohler. We also explore advanced features of WKO, training peaks, exert and intervals that ICU.

Trevor Connor 27:42

We use the term deep dive a lot around here, but this is our deepest dive yet into performance data analysis. Follow our advanced performance data analysis pathway at fasttalklabs.com.

Organizer Responsibilities

Trevor Connor 27:56

So let’s talk about some of the things that organizers can do. And I’m going to throw one, which is be preventative. You might be a race organizer who’s done a lot of cycling and look at this one particular hill or a corner or whatever, and go, “Oh, that’s exciting. Let’s throw that in, that’s gonna be a lot of fun.” That doesn’t mean that everybody who’s participating is going to see it the same way or be able to handle it. I think of one horrible tragedy where there was this great event in Ontario, but they decided to have a descent on the biggest, steepest hill in Ontario, Canada. And a lot of riders up there don’t know how to descend, because it’s just not a hilly place. And this poor woman who was a GranFondo wasn’t ready to handle that dissent. She went off the road and she was paralyzed.

Griffin McMath 28:43

Oh, my gosh.

Trevor Connor 28:44

So they didn’t do a descent like that again, in that course. But that’s sort of things you look at of, I might be able to handle this, a pro might be able to handle this. But what about all the other people in the event? Maybe this isn’t the best idea to have this on the course.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 28:58

Yeah, you can have mechanical failure, even if you are an experienced bike handler. High speed front wheel wobble is something that actually occurs about 50 miles an hour in a lot of bikes. It’s that one time you think, “Okay I’ll let her go and I want to hit 50 for the first time in my life!” And all sudden your front wheel starts to wobble and you can’t ever get it back under control. So prevention, it’s having good mechanical gear.

Griffin McMath 29:25

And sounds like route choice of the actual race organizers.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 29:28

Oh, absolutely.

Medical Culture

Griffin McMath 29:29

I have a question. When we talk about prevention, something to me, it’s glaring that we’ve talked so much about race organizers in the medical sport. I’m thinking about this from someone who’s training for my first endurance race, and I still have to register. So I have no idea what comes in a packet or what that looks like. How do you educate the athlete of if this happens during the race, this is what you do. You talked about rules of reentry a little while ago, and I thought, “I didn’t even think about that. Am I allowed to get back up and move, and where would I go?” So how do we educate athletes prior to race about what to do?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 30:04

There’s usually a blurb in the – we use call it a race Bible, which was a multi page thing that covered all such incidents, rules and etc. Now it’s usually the race fryer that says medical care will be provided at the start finish line.

Griffin McMath 30:18

Yeah, but what does that look like? And do people even read these things? So what are what are common?

Trevor Connor 30:23

I did. I always read the Bible.

Trevor Connor 30:24

Yeah, but Trevor, you’re so great. You read between the lines. You do it all. But I’m a person who cooks and think, I know better than whatever it is. I don’t read instructions, directions. Overrated. So are there certain things that should be common knowledge?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 30:36

You can’t hold a race that’s certified by the USA Cycling without medical care at your event. And they have some basic requirements for them to give you a certification for the race. Gravel races, one of the reasons they choose to hold a gravel event is that they don’t necessarily have to have certification from USA Cycling. And they don’t have to buy the insurance that’s provided by the Federation.

Griffin McMath 31:01

I guess I mean, like from the athletes perspective. Because I see videos of people cycling, and an accident happens and everyone behaves differently. And it’s like, there’s no cultural standard. And so many of these videos, some people get back up and plow right through. Bleeding out –

Trevor Connor 31:17

You’re right. It is very cultural. Certainly, when I was racing, there was a hard man’s attitude towards it. What I learned was, you hit the pavement, first thing you do is check to see all four of your limbs are working. And if they’re working, get back on the bike. It was just that simple. And as you said, you had people that were concussed, getting on their bikes and wobbling down the road. And I would be lying if I said, I didn’t get on my bike probably a bunch of times where I shouldn’t have. So maybe part of the answer here is you need people that can help the rider make the choice. And that’s the thing if the ambulance is far away, that rider might already be deciding if they’re going to get back on their bike or not before the ambulance can get there. So if there’s race officials, if there’s other people there, they should have some basic knowledge of being able to assess somebody to say it is a danger for you to get back on the bike and keep racing.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 32:11

GranFondo’s gravel races are races, they’re timed events, but they’re more of a participatory event. So I remember going to the line at Unbound. Two years ago, for the 50 mile race. I looked around and saw there’s 300 people at this line, there’s 20 of us that think we can win. Right? So there’s 20 of us that are actually racing, the other 280 would stop. You know what I mean? If you’re a participant and somebody is in danger, they’re gonna stop because they’re not really worried about their finishing time. The first 20 guys probably aren’t gonna stop.

Griffin McMath 32:49

That’s such a good point. Now we’re talking about the ethics and what you’re there for. Because you’re the one hurt, you can reenter the race where you were?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 32:58

Well, you can’t reenter the race where you were. If it’s a professional race, you can hang on to the medical car or medical motorcycle, and they will keep you in the race. But without that assistance, nobody’s going to helicopter you back up to where you were.

Griffin McMath 33:12

I misheard you earlier. I was like, that’s surprising.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 33:14

You got to get up and chase.

Griffin McMath 33:15

Okay. Yeah.

Trevor Connor 33:17

But there is, I think I know where you’re going with this. And it’s hard to do. If you are a participant in the race and something happened, somebody is potentially hurt. Somebody’s got to stop. Somebody’s got to stop and help. And there’s that assessment of am I somebody who can help? Do I have the necessary knowledge here? But it can be hard, your adrenaline’s going, you want to keep racing, you paid to be at this event, it’s hard to say I’m going to sacrifice my event because that person’s lying on the road, and I need to help them, but you need to do that. And I can give a example from two weeks ago. I went on one of the local group rides, and there were organizers for the ride. So there was meant to be a ride leader and a guy at the back who was following. As we’re heading back to Boulder, of course, they got into race. As a matter of face it was the ride leaders who are splitting up the field. And this wasn’t a medical incident, thankfully, but this woman in the group got a flat tire. And the ride leader and ride follower just went right by her and ignored her. And I stopped. Yeah, I wanted to be there in the race. I’m like, somebody’s got to stop to help. She didn’t know how to change a flat. She would have been stuck out in the middle of nowhere.

Griffin McMath 34:27

I think this brings up my last culture question. I promise, then we can dive back in. But when I see videos of crashes at cycling events, it looks like what I said earlier, people just kind of plow through. And it’s eye on the prize, finish line. And maybe this is partially just logistics with the actual bike. But I see so many of those videos that go viral online of marathons where someone is falling or something and the person will come over and arm and arm they run across the finish line. Do you think there’s a sport discipline difference in the culture of how competitors treat each other?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 35:01

Well, with a bicycle it’s hard to help them across the line.

Griffin McMath 35:04

Right.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 35:05

You know, many of us in the medical world have questioned those assisted finishes. Should they not have been attended to by medical personnel? They’re obviously in medical distress. They’re disoriented.

Griffin McMath 35:17

Oh, yeah.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 35:18

So are they dehydrated? Are they having a cardiac event? We don’t know. So that good sportsmanship may have prolonged the time before the medical care was actually performed. Right?

Griffin McMath 35:30

People probably don’t even think about it. They’re like, this just makes me feel good.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 35:33

I’m a different person when I have a number on. I am a totally different person when I have a number on, then I am sitting here being really smart about all this.

Griffin McMath 35:40

What a quote, Andy. We’re gonna pull that quote right there.

Trevor Connor 35:46

And the thing that’s different about cycling that does impact this, and it also impacts how team managers deal with when one of their athletes crash. Is the peloton, the drafting effect. If you go down and it takes you more than 30-40 seconds to get back up. You’re never catching the peloton. If you’re a minute or two off of that peloton, you’re never seen again. Your race is over. So you just get into that mindset of if you crash, you get back on that bike as fast as you can. That’s not the case in a marathon. You might be a little bit slower. If you stop for a minute, but you’re losing a minute, a minute and a bike race is done.

Griffin McMath 36:23

That’s where you got to have such a great mental game, I feel, because otherwise you see the videos of people get pissed and throw the bikes like why do I even get back on at this point type of thing? Wow. Well, thanks for taking me down culture lane, guys.

Trevor Connor 36:36

But it’s a really important question because as we said, the issue I have with medical support is medical support might be four or five minutes away. And all that riders think about is “I gotta get back on my bike immediately or my race is done.” And it leads to bad choices before the medical crew can get there and do something.

Griffin McMath 36:53

Or Andy on a motorcycle behind you going, “Please pull over,” on a megaphone.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 36:58

Oh, I just go up beside them. They were so accustomed to me being there. I could be right in the middle of the group. Talking to riders. I mean, it was they were so accustomed. For me, they knew me. And I could be in in the group truly, I could ride for the back of the group, split the group and “Hey, I need to talk to so and so.”

Griffin McMath 37:17

So while they’re still racing, you can be assessing someone in conversation, be like, “Maybe we pull over? Maybe?”

Dr. Andy Pruitt 37:23

Oh, absolutely. No, I dressed wounds. I relocated dislocated fingers on the roll as bikers.

Trevor Connor 37:31

You will be amazed, the things that you can do. There’s a great video of Seth fixing his derailleur on a descent.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 37:38

Yeah.

Griffin McMath 37:38

Guys. Not that I want to get injured, but I kind of want to see this in action right now. So maybe after the podcast, we’ll get on my bike.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 37:45

I actually want to tell a funny story. Rudy De Gerrans ultimately became a world champion. But at this time, we were in the middle of the Tour de Pont. And he came back and was like, “Hey, Doc, my Achilles is killing me. My Achilles is killing me. What can you do?” Well, I’m not gonna, we’re not going to take his Achilles heel. We’re not going to assess it here. So I pulled out a tube of lidocaine jelly. He held on to my driver shoulder, and I massaged his Achilles with lidocaine jelly, pulled back up a sock and said, “Rudy, you’re gonna be great.” And he rolled off.

Griffin McMath 38:19

You massaged someone during a race?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 38:21

With lidocaine. It wasn’t gonna do a thing. It didn’t do a thing. He thought I fixed it.

Griffin McMath 38:27

Oh, my gosh, this is so cool. I think that you have a different expertise to provide that. So I can see how if I was a pro racing these events, I’d want to be paying a little bit extra of a registration fee to know that I had someone like you for medical support, rather than having me get off my bike and do it. Oh, what a story.

How to Respond to a Medical Emergency

Trevor Connor 38:46

So let’s shift gears here a little bit, let’s talk about some of these incidents and what you should be doing both as a writer and as an organizer volunteer at the event. So the first one, because this happens a lot. There’s a big crash. And obviously, there’s a difference being a solo rider just taking a little skin off. And what I was describing earlier, like that crash at Hilo where 70 riders went down. But you’re in the car, you’re an organizer, you’re a corner volunteer and you see this crash. What are the first steps? What are the things you should be doing?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 39:19

The difference is, is that one person or you can zero your attention into them? Or is it a mass casualties? Right? So the guys that jump up and who assess their bicycle and get back on it, you’ve got to assume they’ve got mental faculties and that nothing important is broken. They’re gonna ride away from you. You have to assume that. I always went to the slowest mover first, right? That’s the way I chose them. Whether it was two football players that hit themselves, or whether it was a multitude of bike riders that crashed. I chose the slowest mover first for me to assess. We don’t want to go into first aid skills here about not moving the neck and all those things. But making sure they have an airway. Are they breathing? Do they have a pulse? All those things, you have to quickly assess. They’re gonna start moving on their own most likely unless they’re unconscious. So they can actually tell you a lot about what’s going on by what they do. Broken necks rarely get up and get back on their bike. Rarely. Can’t happen. So that’s how I was self selecting who I attended first.

Trevor Connor 40:24

So if I’m a corner volunteer and I see a crash, and I’ve got limited medical training. I’m assuming it’s get on the phone, get on the radio and make sure the right people are getting there quickly.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 40:35

Well, most first aid certifications tell you to call 911 first. Before you get enthralled into personal assessments, right? So call 911 first. And say, “Hey, we’ve got a mass crash at third corner, blah, blah, blah, 10 guys down. Most are riding away but three aren’t.” And then go take care of them. That’s what I would do.

Griffin McMath 41:00

So first alert.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 41:01

And then directing traffic is a lot of it. If the groups come apart, there’s more groups, more pelotons coming at you. So there’s follow cars. Directing traffic, so that there’s no further injury. There’s so many things a corner marshal has responsibility for, that when they volunteered, they had no idea. The big races have crews of volunteers that they provide housing for. So it’s a multi day stage race. For example, Tour California, Coors Classic, blah, blah, blah. There was a bus that moved the volunteers from stage to stage. You had locals, yes. But most of these were professional volunteers. And professional corner marshals that were moved by the race. Housed by the race. Fed by the race. And they had a course map and an assignment and they were dropped off at their spot and picked back up and moved. That’s the way you do course marshals. Not everybody can do that. That’s the ultimate.

Trevor Connor 42:01

And you brought up a really good one. Sometimes crashes happen where there’s limited visibility. You come over a hill and then come down the other side and crash there. There could be a car coming. There could be another field coming. You need to get one of your volunteers up at the top of that hill, flagging everybody down and saying stop, there was a crash up ahead.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 42:21

One of my second or third bike races ever. And I still ride with this guy. Crashed in front of me and I rode over him. And he’s showing me the tire marks on his arm. It’s the end of the razor. It’s the heart man. When I have a number on him, I rode over him and left him for dead. But he finished it. We’re still friends.

Griffin McMath 42:45

You kind of get it. You’d maybe do the same.

Trevor Connor 42:50

When I broke my collarbone, the guy behind me rode over me. I found him later. I’m like, “Good on you.”

Dr. Andy Pruitt 42:57

Good bunny hop.

Trevor Connor 42:58

Anyway, those bikes skills. So let’s talk about the incident I dealt with. Heart attack or stroke. Somebody’s in the middle of the field, or in the middle of an event and they fall over. Because of that. You’re the volunteer, you’re the race organizer. What do you do?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 43:14

As I said, 911 first, right? Call. You’ve got an incident, they’re not moving. It’s obvious that they’re going to be down a while or they’re not moving well. Alert first. And then are they moving? Do you need to protect head or neck? Do they need CPR? If you got someone who you think is not breathing, and you think has no pulse, even bad CPR can save a life. Just chest compressions. Forgetting about open airway to move air. Forget about the breathing aspect of CPR, right? But in a perfect world, you’ve got two people. One providing breasts and one providing chest compressions until the professionals arrive. You just can’t stand there and do nothing. You just can’t panic. And if you have volunteered to cover that corner, you need to be prepared for the worst. I think all athletes – and I use that term loosely – all participants or active people should have basic first aid training. I don’t care if it’s an online course. Whether it’s a CPR or – I don’t care what it is. Recognition is half the game. “911 I think someone’s having a cardiac event. I think someone’s -” Basic understanding. You’re going to encounter it. You think, “I’m gonna go be a racer, I don’t need medical training.” You don’t know what you’re going to encounter out there. The middle of nowhere in the Flint Hills of Kansas, you don’t know what you’re going to encounter.

Griffin McMath 44:43

Who are the people outside of the medical enclosure? We’re talking about corner marshall.

Trevor Connor 44:47

Yep. Corner marshall, volunteers, people that are in the vehicles. In front of or behind the group. The race organizer. A lot of people that make an event happen.

Griffin McMath 44:58

I’m guessing each of them is equipped with a different fanny pack, if you will.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 45:03

If you’re a professional first aid provider, you have a pack, backpacker, or fanny pack. I have this still in my trophy case right now from the 96 Olympics. They made me this enormous fanny pack that I would wear as a fanny pack. But then when an incident occurred, I would spin it around. So it actually sat in my lap between me and the driver. And that’s how I would administer first aid out of it. It had everything in there. In the saddlebag where my defibrillator, my oral screw, things that I’m going to need. And so when a crash would happen, I would run to the athlete with my fanny pack. My motorcycle driver would bring my danger bag out of the saddle bag. Again, that’s the gold standard. That’s not going to happen at the Boulder Roubaix.

Incidents to be Prepared For

Trevor Connor 45:54

So let’s talk about another type of incident. This is where I could tell a bunch of stories. There’s an incident with a car. With a driver. The other car on course, car doing something dangerous. And you know, one of the stories I can tell is there was this weekly crit. Just outside of Boston that I used to volunteer at. It was on Sunday mornings, fairly well known crit. And it was an industrial park. For the most part, everything was closed, except there was a fitness club there. And we had one week where the whole peloton is coming towards the driveway for this fitness club. And there’s a woman pulling out of the fitness club and she’s very angry about this bike race. And she was getting ready to just pull out in front of the entire peloton and I literally had to jump onto the hood of her car to stop her from taking all these riders out.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 46:46

No care for stupid.

Griffin McMath 46:49

The other quote we’ll pull.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 46:52

We call them civilians on course. And that was an alert that meant there was somebody unassociated with the event, on course. Professional races closed the entire road. Local races can only control one half of the road. So we have the yellow line rule, which doesn’t let riders go over the yellow line on to oncoming traffic. But even then, that you will get a civilian in the race by accident. There’s nothing a corner marshal or first aid guy on a motorcycle can do about that. They’ve got to sort themselves out and they typically do with police help. Sort themselves out. But like I said earlier, majority of cycling crashes occur in training. They don’t occur in racing. I think that you might encounter a downed cyclist while driving. Right? So the all those same rules apply. 911. Then assess. I think we’re gonna get to this, but when does a rider report to an ER? When does a athlete report to their physician? How do we sort through those things? But we’ll get there I think.

Trevor Connor 47:59

Yep. Any other incidents that happened at events that you can think of that anybody who’s a volunteer or race organizer needs to be aware of and needs to know, what the steps are to handle?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 48:13

Well, there’s always the question. Should I transport an injured athlete in my personal vehicle? And the laws vary from state to state. But usually, there is a good Samaritan Law covering any non medical personnel who was attempting to provide first aid or transport. So if you don’t mind, get little blood on your leather seats. I do think that if you encounter someone, especially in the countryside, that has crashed and in need of help, that you should not be afraid of transporting this person in your personal vehicle. So that’s just a sidebar that I think is important.

Trevor Connor 48:58

Good. So let’s go do what sounds like you really want to cover. Which is now let’s talk about the, you’re the rider, you’re the participant in an event. And yes, when you go to that really big race, like the Tour de France or Tour of California, you’re gonna be well covered. You don’t have to worry about that. But let’s talk about people going smaller local events. Let’s say you’re going to that gravel event where you know there’s limited medical support there. They can’t really get on to a lot of the gravel trails, so you’re kind of on your own. What do you need to do? What do you need to bring with you? What do you need to be careful about?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 49:34

Are you asking me whether I carry a first aid kit when I’m racing Dirty Kanza? No, I don’t. That reminds me of another story. A whole ride full of doctors and there wasn’t a band aid amongst us. Anyway, the most common cycling injury is road rash. So there’s asphalt road rash. Different than gravel road rash. You would think the asphalt would be somehow cleaner but the oils and chemicals in the asphalt are really poisonous. And can actually leave a tattoo in your skin. So an abrasion is the number one cycling injury. You crash, you get back up, you finish the race and your bloody shorts and they come to you. Do you need help? No, I’m okay. Well, that’s the wrong answer. They have all the goodies. They have the sterile scrub brush. They’ve got the xylocaine jelly. They’ve got all the things to help making clean that wound a bit more comfortable. So I encourage people to seek out the finish line start line first aid folks. If you have road rash or gravel rash, to get it cleaned immediately. The longer that bacteria stays in that wound and it scabs over before you get home, the more chances you have of getting an infection. Or having gravel embedded in your skin. I can show you the gravel in my elbow. So really encourage people not to be so stoic about their road rash. They’re embarrassed. Their butts hanging out of their Lycra. No, you should get it cleaned as soon as possible. Especially if you got a long drive home, right? The other ones are collarbones. Many times, you’re not sure whether you’ve broken a collarbone or not, right? The periosteum can hold the pieces together. It can function fairly well. If there’s any doubt about it, I encourage an x ray. I know emergency room visits sometimes can be long, they can be expensive. But diagnosing an occult fracture, kind of a hidden fracture early on, is going to save you time in the long run. So a mid shaft, collarbone fracture, the proximal and distal ends are a little bit different. The distal end is out to the tip of your shoulder. And the hands on exam is gonna say “Oh, I think you’ve got an AC separation.” Well, many, many acromioclavicular or AC joint separations have a community to distal end of the clavicle fracture as well. That can be addressed similarly, but maybe they shouldn’t be addressed similarly. Proximately more toward the sternum, the sternoclavicular joint. When it’s injured, or dislocated or fractured, becomes a nuisance for the rest of that patient’s life. If it’s not addressed appropriately. I don’t want “Oh, I broke my collarbone. I’m now official bike racer.” No, it’s not that simple. Welcome to the club, dude. But make sure you get assessed. Especially if it’s not so obvious if a fracture is one end of the clavicle or the other.

Griffin McMath 52:31

Yeah, immediately. The healing is very different.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 52:35

So we think about abrasions as being the number one. Collarbones being number two. Hematomas on the hip may be our number three, that are really really really undertreated. The most undertreated injury and cycling is the hip hematoma. And for the listeners, a hematoma is basically an isolated pool of liquid. Mostly blood, but not always blood. That accumulate between the layers of tissue. And if you get to a hematoma quickly and compress it, you can squeeze that fluid into the other tissues. It’s going to resolve rather quickly. But again, a lot of us go “I got this big bubble on my hip, I’m going to ignore it. I’m a tough guy, it’ll go away.” No, you want to seek medical attention for that hematoma. I’ve seen them become infected. I’ve seen people get septic from hematomas. Especially if there’s an abrasion on top of the hematoma that they can translate with each other, communicate with each other. I really do encourage draining of hematomas initially. The longer that fluid stays between the layers of tissue, the more likely it is to scar itself in like a pearl. And stay in there in this thick scar tissue between the layers. And for women, it’s very deforming. Truly gives them saddlebags. It’s deforming on guys too but we don’t tend to care as much. But really, if you’ve got a hematoma, you’ve got this jelly filled sack of fluid on your elbow or on your hip. They’re the number one unaddressed injury that needs to be addressed initially. Early on.

Griffin McMath 54:09

You said a couple things. First off, the asphalt tattoo blows my mind. I didn’t know that was a thing. You said something and Trevor caught me cringing over here. The collarbone. I think this is one of the ones that people don’t take seriously enough. And what people don’t understand is that clavicle is covering a very, very intricate, very sensitive, very high risk area in your body. A broken clavicle can cut into that. It can be really detrimental. So I cringed because my brother I think has broken his clavicle a couple times. And every time I heard those stories, I’m just like, “Oh my gosh, you were so close to XYZ happening.” Just watching that kind of makes you queasy. But you talked about the hematoma you talked about even how some people can be embarrassed about it and think of it more as a vanity. There’s this physical appeal, right? I’ve got these scars. I’ve got these rashes. I’m just gonna hide it. No. Address it immediately. There’s no embarrassment there. The road rash, the tattoo, I’m gonna have some weird Google search results later, Trevor.

Trevor Conner 54:09

You should check these out. I’ll spare you the gory details, but to make your point about get it clean right away. I had bad road rash early in my career where I didn’t do that. And I will still say one of the most painful experiences of my life as it got infected. I went to the shower with a piece of steel wool and a bottle of vodka.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 55:36

It was semi right.

Griffin McMath 55:39

He didn’t say how the vodka was being used. Was it to mask the pain or to clean?

Trevor Connor 55:43

It had multiple purposes.

Griffin McMath 55:44

That’s what I thought. There’s a great point though. This was early in your career was that around the time where the culture was this brutalist thing? And that road rash was a badge of honor?

Trevor Connor 55:53

That was around the time when I was just an idiot. Didn’t know how to take care of myself. So even among the hard man suffer through it, those guys are going into the medical tent and getting cleaned. There’s a difference between fighting through it and just being dumb.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 56:10

The really good start finish line medical crews will have a lidocaine jelly to numb the area. Of course, then they’re going to scrub it off. Then they’ve got a sterile beta dye and impregnated brush. Yes, they’re going to brush your abrasion. But they’ve attempted to numb it a little bit early on. They’re going to have nonstick dressings. They’re going to have either 2B grip, which is a slip on leg of long underwear that will hold the dressing in place, or burn netting for joints. They’re gonna have all the right stuff. That then you can go to the drugstore and attempt to duplicate, right? If you’re a bike racer, or a mom and dad of a bike racing family, you should have in your car 2B grip, burn netting, nonstick gauze, a sterile scrub brush. These are just the basic things you need to get that debris out of those wounds as quickly as possible. I love Tegaderm. But it’s not to be used early on. You really need Tegaderm the second ,third and subsequent days. Tegaderm is almost like a second skin if you will, that covers the wound and can be sealed around the edges and holes. The wound environment is contained. And it really does expediate the healing and minimize the scarring. And it can be purchased in multiple sizes at the drugstore.

Trevor Connor 57:43

Tis the season for spring knee. As sunshine and spring weather inspires us to ramp up a ride and mileage, our knees don’t always keep up. If you got knee pain, we have the solution for you. Fast Talk Labs members can follow our knee health pathway, featuring Dr. Andy Brewer. See the introduction in the knee health pathway at fasttalklabs.com.

Be Prepared

Griffin McMath 58:04

So I have kind of one last question for both the race organizer and then the athlete that I would love your thoughts on. From the perspective of an athlete, what’s one or two low lift things that they can do to be more prepared? That aren’t going to be super expensive, that aren’t going to be a huge effort. A couple of low lift things that they can do immediately that is going to change their ability to be prepared for a medical event.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 58:31

About the rider and or the event organizers?

Griffin McMath 58:33

Both.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 58:34

Because I think they’re both very similar.

Griffin McMath 58:35

All right.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 58:36

One is your minimum basic first aid and CPR training. I don’t think anybody should think about attempting to be an athlete without it. Juniors. Juniors tend to do stupid things. They’re really strong, they’re fast, but they tend to do silly things. And they’re going to knock each other down. And your coach or parent are not always going to be close. So I think for a parent to make sure that their 12 year old and older, has some kind of basic recognition medical care. I was a boy scout early on. So I was eight or nine when I was shown basic health care. So that’s number one. That goes for both racer and the event organizer – who needs to be looking for that medical sponsor. That’s either come through with a budget or with staffing and expertise. It sounds silly because it’s a self fulfilling prophecy, right? If an orthopedic group sponsors a bike race, they’re gonna get business out of it. They’re gonna become known as the guys who care about bike racers. Even if you don’t get it that day, it will circle back around .It’s well proven that orthopedic groups that sponsor bike races and bike teams are well reimbursed and much cover their expenses. For the rider you should have in your car, a first aid bag. And it does need to be replenished on an annual basis because the dressings dry out, the tapes dry out, all those different kinds of things. Tegaderm is pretty premium, might be here during the next Ice Age if the package hasn’t been opened. But a basic first aid bag with brush, the cleanser. If you can tuck your local dock into giving you a tube of 5% lidocaine jelly. Not ointment, jelly. Very different. So you have that in your bag. Those are crucial, crucial things. A sling. Wow, a sling. You know, a lot of gravel writers use bandanas now, and I’ve seen two bandanas tied together to make a sling.

Trevor Connor 1:00:31

UnBound has pretty good medical support. So let’s say you’re at one of those local gravel events, where you find yourself out in the middle of nowhere. Or even worse, you’re just out for a ride in the middle of nowhere. You crash. You can tell that this is more than road rash. More than a little bit of pain. Something is wrong. And you’re on your own. What do you do?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:00:57

Hopefully you took your phone. I mean, I don’t know many people that don’t train without a phone these days. And hopefully you’re in cell phone range, right? You got to crawl up to the side of the road, where passing driver can find you. Call 911. Call your parents, whatever. There are actually helmets now equipped with crash detection. There’s watches that are equipped with crash detection. They’ve got an accelerometer in them and they know when you’ve dropped it versus when you’ve crashed. So there are ways to alert family.

Trevor Connor 1:01:29

My Garmin does that. Unfortunately, it’s called my mom a couple of times now.

Griffin McMath 1:01:33

I was just about to say I feel like Garmin is the go. That’s when you’re in places that don’t have service.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:01:38

I just wasn’t gonna mention – but you’re right. Yeah, I think it is. Specialized helmets have have it in them. There’s others. I know, Spoke Safety is working on an accelerometer inside their apparatus. So tell people where you’re going. I set off on a solo gravel ride from my mountain house. It’s gonna be a five hour ride. I was gonna be up on the waterboard road in Grand County. So I’m in the middle of nowhere, right. And I decided I was tired. And I was going to take the first ascent back to the valley floor. I turned left on this gravel ascent and ended up being so steep. Lost control, ended up in the ditch. It was a dead end anyway. I’m at the bottom of this ravine. Fatigued. Nobody knows where I am now. I hiked back up. It was so stupid. Just so, so stupid. But in fatigue state “Ah, man, I’m tired. I need to take the shortcut.” And of course, it was a long cut. The other story is UnBound. They have a 350 mile race. Think about this 350 miles. Takes 24 hours for most people. There is no rolling medical enclosure. So there was a story last year, that in the middle of the night, a racer had fallen on a bridge, slid under the guardrail and into the creek. Only because people saw it happen. There were racers close enough to him. That stopped, pulled him out of the water, got him back up onto the side of the road. Otherwise, he’d probably still be there today. So self help those kinds of adventure races. That’s not a bike race in the typical sense of the word, right? It’s an adventure race. Their only food, they stop at grocery stores. And that’s how long they’re out there. There’s no feed zones. So only because fellow competitors saw this guy slide under the guardrail into the creek on the bridge, was he saved. He actually got up and raced. So everybody should have basic first aid training. And everybody should have a good moral compass.

Trevor Connor 1:01:38

The last question, because you asked this and I just want to make sure we’ve fully answered it, is knowing when to visit ER or your primary doc and a loved one. I can teach from my own stupidity. So I’ll give an example. Last year where I was on the Boulder Super Training ride, a guy in front of me went down. I crashed over him. Did the stupid – put my hand down. Wrist was hurting. And for the next four weeks, I was like, “It’ll be fine, just some inflammation.” And it wasn’t going away. So finally, at that point, went to see the doctor and the doctor said, your wrist is broken. I went “What can you do about it?” And she said, “Four weeks ago, I could have done a lot.”

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:04:30

Yep, you’re right on the money. That is a perfect example. Something that you think is a sprain or strain and will self resolve and it doesn’t begin to turn the corner in 72 hours, deserves a visit. It is most likely going to be an underlying fracture, or a soft tissue tear that needs attention. And the wrist is a perfect example. Lateral ankle is a perfect example. Distal clavicle is a perfect example of all of these things. So when in doubt, don’t cowboy up. Go see your doctor. I think that abrasions, whether you cared for it appropriately or not, need to have a mindful eye,. Fever, nausea, night sweats, lymph glands, swollen neck, armpit, groin, are signs that you ought to be thinking about an infection that’s downstream from those swollen lymph nodes. But nausea, fever, night sweats, swollen lymph nodes are a time to go see the doctor. Even if you’ve treated it appropriately. There’s no reason not to follow up.

Griffin McMath 1:05:35

Andy, this is a great point. And I think that this is a great list to bring up. Because once someone starts to accept the symptoms as a new normal or just an inconvenience, you become a little disoriented from what is actually acceptable. And you start to let things slide. You’re like, “Oh, it’s only a little bit worse.” Or like, “It’s fine. It’s just the same, it’s not getting better.” So I think maybe even having someone else that you can report your symptoms out to to hold you accountable. So that if you start being a bad patient, if you will. Or not being attuned to this, someone else can go, “Hey, that’s not okay. That’s not normal.” So maybe part of this advice, as well as making sure that you’re communicating with a coach, a parent if you’re a junior, like what are the symptoms? And then following up with checking in and up for 72 hours. And someone else holding you accountable to “No, no, no tough guy,” or “No, no, no, this is not no big deal.” Again, go to the doctors.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:06:30

Really good point. I think disorientation. I had a friend call me. Crashed train ride, solo train ride. And he was calling to check in. And I could tell by his speech that he was disoriented and not right. Somehow saved his phone, we got the phone call made. But, man, I said, “Is your wife – ” “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” So we put her on the phone.

Griffin McMath 1:06:54

And have them take you at that point. You’re a danger to someone else.

Take Homes

Trevor Connor 1:06:58

Well, I hate to say it guys, I think it’s time for take homes. It’s been a great conversation. Dr. Pruitt, you know the way this works. What’s your most important message for our listeners to take from all this?

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:07:10

It won’t take me the whole minute to do this, because I think I’ve said it several times. If you are an active individual, and you’re out amongst other active individuals, r you want to call yourself an athlete, whatever that is. You need to have basic first aid training. Not only for yourself, but for someone whom you might encounter. On your ride, run, climb, whatever that is. Number two, be self aware, right? Be self aware. Postinjury. When should you seek medical care? And sooner is usually better than later. And for the event promoter seek a medical sponsor.

Trevor Connor 1:07:53

Fantastic. Griffin?

Griffin McMath 1:07:54

Well, you just stole one of them. I’ll piggyback on that though. Just remember that everyone has a business, including physicians and medical systems so they might be willing to chip in too. So going into that everyone has something to gain from that. I think for the athlete, or whomever, it’s such an easy little nugget. Lidocaine jelly, not ointment. I wrote that down. Because you tell someone, “Hey, will you go pick me up some lidocaine?” You’re sending someone on a wild goose chase to just pick up whatever. So I love the percentage that you provided and saying jelly. I think a couple things came to mind, to me, for the athletes to understand rules of reentry. To understand who they have to look to when a crash happens or an injury happens. And then to understand that sooner is better. Immediately. Even if you’re feeling disoriented after, just maybe sit down. Wait for someone to help you before you get back up. Because you could actually end up hurting yourself again, or being so disoriented that you end up hurting someone else too.

Trevor Connor 1:08:52

So my take home goes right back to where we started at the beginning of this episode. Which is just that important message that if you’re listening to all this and saying, “This doesn’t apply to me. I’m not a race organizer. I’m not a volunteer.” Much better chance than not at some point, you’re either going to be the person lying on the side of the road, or the person who encounters the person lying on the side of the road. You might just be out for a ride and encounter somebody. I know I have a bit of strange luck. I have now twice been on the side of the road with somebody who was dying. This happens. Make sure you know what to do. And I look back on both of those incidents, and I’ve talked to doctors. They said there was nothing I could do. And I still go, “Could I have done more? Had I had better training, could I have done something?” So you don’t want to be in that situation where you end up being like me. At the wrong place at the wrong time. And find out later there was more you could have done for that person.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:09:49

The Good Samaritan Law is there for a reason. And it is for Good Samaritans. Not medical professionals. To provide first aid when needed. And without fear of repercussions or legal repercussions. So the Good Samaritan Law is a really important thing.

Trevor Connor 1:10:05

Well, Dr. Pruitt, always a pleasure. Thanks for joining us today.

Dr. Andy Pruitt 1:10:09

You know, I enjoy it. So anytime.

Griffin McMath 1:10:12

That was another episode of Fast Talk. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. Subscribe to Fast Talk wherever you prefer to find your favorite podcasts. Be sure to leave us a rating and a review. As always, we love your feedback. Tweet at us @fasttalklabs. Join the conversation at forums.fasttalklabs.com or learn from our experts at fasttalklabs.com. For Dr. Andy Pruitt and Coach Trevor Connor. I’m Dr. Griffin McMath. Thanks for listening!