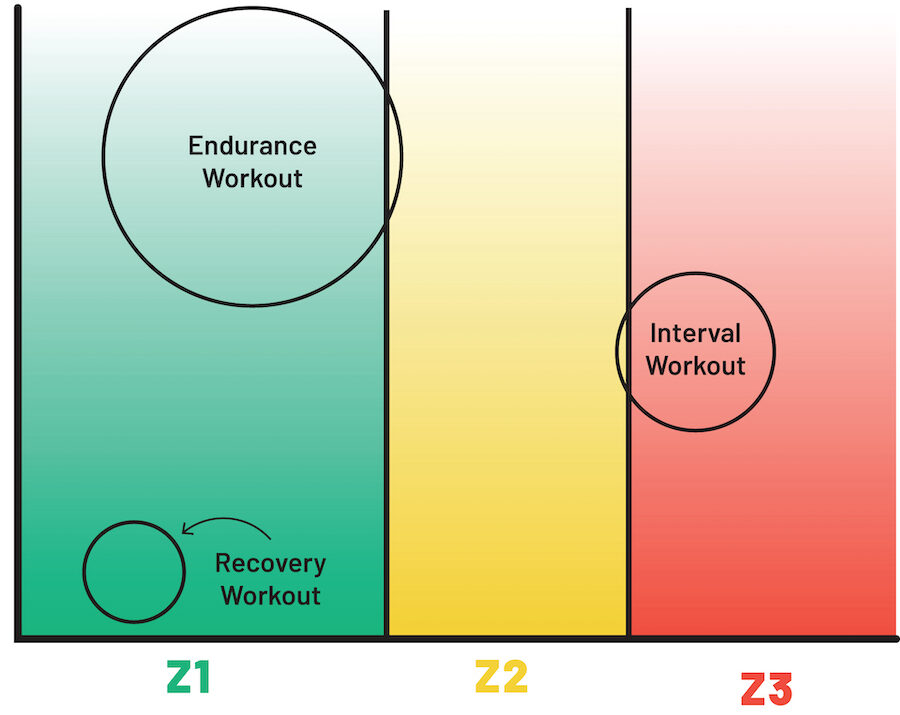

To truly polarize your training, you need to focus your training in two key zones. Coach Trevor Connor explains how this works for the sport of cycling, but the physiology applies to all endurance sports.

To truly polarize your training, you need to focus your training in two key zones. Coach Trevor Connor explains how this works for the sport of cycling, but the physiology applies to all endurance sports.