The picture that’s often painted of our athletic potential after our mid-30s is a grim one. The palette seems to have one color: decline. There’s no doubt that training as a masters athlete comes with unique challenges.

It’s generally been accepted that there’s a decrease in muscle strength, in maximal heart rate, VO2max and efficiency, and ultimately, a decline in performance. Scientific research comparing world records across all age categories draws this conclusion. A gradual decline starts around 35 years of age and falls off precipitously around the age of 70.

It’s been considered an inevitability. So why, then, are age-group world records catching up with those of their elite counterparts?

The research and assumptions about masters athletes are being re-evaluated. Inherent bias—caused by the cross-sectional nature of the research and generational differences in training and participation—is raising questions. How much of that decline is actually due to age? The new answer to the age-old question is: not as much as we thought.

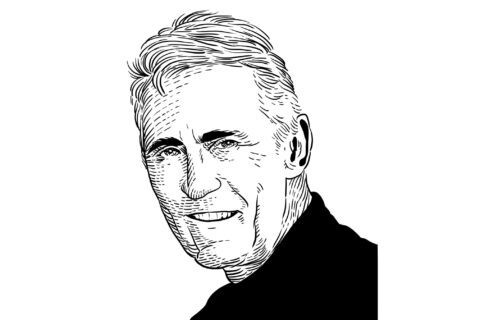

Legendary mountain biker Ned Overend, the sport’s first world champion, stands as the poster child of age-defying performances. He still lives in Durango, where that event took place in 1990. He also continues to join the Tuesday night group ride, which attracts fast “kids” from Fort Lewis College along with local mountain bike and road pros.

“I feel I do well at that ride because I’m able to close those gaps and join the break when a lot of guys fail behind me,” says Overend, who won the prestigious Mount Washington Hill Climb at the age of 56.

Age seems to have mostly left Overend alone, though he admits he doesn’t have the same sprint or ability to go hard off the gun that he used to have.

Why the Research Had It Wrong

The big issue with past research defining age-effects is that it’s cross-sectional. This means that since it’s very hard to track changes in a single athlete from their 20s through their 80s, most research compares current elites to current masters.

That poses many issues. For one thing, the scientific understanding and culture norms towards sports and training were very different 50 years ago. Better tools may allow current 20-somethings to simply train and age better.

A 2016 review in the Journal of Aging and Physical Activity pointed out that masters also differ in training and participation levels, which may explain the perceived decline more than natural aging. The review showed that masters athletes are improving their performance levels much quicker than their younger counterparts. Researchers explained this trend by a recent sharp rise in masters athlete participation.

The review also found that masters athletes tend to train less and at lower intensities due to factors like work, family, and injury. Maintaining a high level of training appears to attenuate many age-related decrements.

So, what is truly age-related?

While there has been recent debate in the literature about the degree of decline, the one truly inevitable age-related effect is a steady drop in maximal heart rate. Training seems to slow the decline but not stop it.

Because maximum heart rate strongly affects our ability to deliver oxygen, a 2008 review titled Endurance Performance in Masters Athletes concluded that the resulting drop in VO₂max may indeed be a true age-related decline. But even that review cites research showing that maintaining training volume and intensity can mediate much of the decline.

The other oft-cited age-related decline is a loss of muscle strength, particularly in anaerobic fast-twitch muscle fibers. However, this may be more of a “use it or lose it” proposition. In fact, a growing body of recent research shows that adults over 80 can still benefit from starting strength training. They can promote muscle hypertrophy and activate satellite cells.

A 2012 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology was the first to look at the effects of strength training in masters cyclists. Two endurance-only trained groups—one around 50 years old and the other in their 20s—added three weeks of strength training to their program. At the end of the intervention, the masters athletes saw a much greater improvement in muscle strength. The difference in cycling efficiency between the two groups disappeared. In short, strength training helped both groups, but it helped the masters more.

Increased Importance of Recovery

Perhaps the biggest impact of aging is on injury and recovery. In other words, it’s not the years, it’s the miles.

“One of the things I’ve noticed the most is that there are more bad days,” Overend says. “I think what that relates to is recovery.”

According to the 2016 review, there’s little research on recovery in masters, but it appears that physically, masters recover as quickly as young riders. What’s different is it takes longer for them to feel they have fully recovered.

Dr. Jason Glowney, former Head of Medicine at the University of Colorado Sports Medicine and Performance Center, explains that accumulated injuries often limit older athletes’ ability to train. Common issues include arthritis in the knees and back problems. And as the review pointed out, many age-related declines are due to a masters athlete being unable to train like their younger counterparts.

Does anything actually get better with age? Believe it or not, there is something. Relative to their VO2max, masters endurance athletes tend to have a better lactate threshold. And this is not simply due to a drop in VO2max. Long-term, older endurance athletes have demonstrated better capillary-to-fiber ratios and oxidative enzyme activity.

They essentially become purer aerobic specimens, which allows them to remain competitive. As Overend explains, he can still hold his own in the breakaways, he just can’t win the sprint at the end.

Preserving Our Momentum

People often blame age, but a loss in strength and injury—both trainable and avoidable—cause the real problems.

“I think it’s really important to have an open attitude to the fact that you can slow aging with smart training,” Overend says.

Here’s a few tips on how to do that.

Include strength training!

People often consider a drop in VO₂max and efficiency, loss of anaerobic power, and overuse injuries as age effects, but they may actually result more from a lack of strength training. Heavier weights are necessary, approximately 75 to 85 percent of your one repetition max. Therefore, proper form is critical. We strongly recommend hiring a certified trainer.

Include neuromuscular work

In the 2012 study, subjects only lifted for three weeks, which was not enough time to build muscle mass. The improvements were due more to neurological adaptations. Neuromuscular training such as cadence work, big gear work, and short sprints may be able to produce some of the same gains.

High Intensity with less volume

At 53, Overend’s in-lab measured VO2max would have made most aspiring pros envious. He feels a gradual shift towards focusing on intensity over volume has allowed him to maintain this VO2max. Hearing that he only trains 10 to 12 hours per week surprises many. However, it’s still important to limit high intensity work to two or three sessions per week.

Value recovery

Overend attributes part of his longevity to his increased focus on recovery. He regularly takes one week off the bike during the season to rest. He’s also learned to make his hard days hard. On other days, he doesn’t push, instead recognizing the value of a relaxed recovery ride. He also believes he needs more recovery between hard workouts than he did in his youth.

Keep momentum and consistency

“The athletes who are still doing really well, they’ve been consistent,” Glowney says. “That’s probably the secret to staying fit for a long period of time.” Overend agrees that keeping momentum is essential. For older athletes, rebuilding fitness is much harder. It becomes especially difficult if they take too much time off due to injury or let themselves get too out of shape in the winter.

Cross-train in the off-season

Staying fit and avoiding overuse injuries is critical for masters riders. Cross-training, such as skiing or snowshoeing, in the off-season is a great way to address both.

Focus on self-preservation

Staying healthy by not crashing makes a big difference in maintaining fitness and momentum, according to Overend. Despite being a world champion, Overend has no trouble swallowing his ego on “throwdown” rides with younger riders. He’s comfortable making them wait for him at the bottom of descents.