We talk to Dirk Friel of TrainingPeaks to explain how cyclists can use data to make their workouts more effective and productive.

Episode Transcript

Intro 00:00

Welcome to Fast Talk, the VeloNews podcast, and everything you need to know to ride like a pro.

Trevor Connor 00:15

Fast Talk is sponsored by Quarq, maker of next generation power meters including the SRAM Red Dzero power meter, built specifically for SRAM groundbreaking Red Gruppo. The SRAM Red Dzero power meter is compatible with all of SRAM Road group sets. Find out more at quarq.com/dzero.

Caley Fretz 00:37

Welcome back, dear listeners to another episode of Fast Talk, I am Caley Fretz, sitting across the table as always from Coach Trevor Connor. How are you, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 00:45

I’m good. How are you doing Caley?

Caley Fretz 00:46

I am excellent. We also have a special guest in the room today, none other than Dirk Friel, the co-founder and president of TrainPeaks, which is, I think, by far the most popular way for racers to quantify their training, that is turn their training into numbers to help them ride better and faster. Welcome, Dirk.

Dirk Friel 01:06

Thank you so much for having me.

Caley Fretz 01:08

Of course. Quantifying training is actually the subject of today’s podcast, we’re going to define a whole bunch of terms for you. We’re going to talk about what should be on your Garmin and what you should be looking at afterward, and we’re gonna take a step back and have a bit of a philosophical discussion about turning athletes into numbers. Trevor, I think you wanted to start first with a bit of history on this subject.

Trevor Connor 01:33

Really the origins of this podcast, besides the fact that we wanted to get into some of these terms that you really hear tossed around like TSS, FTP, and normalized power, and I think there’d be a lot of value in people hearing what those terms really mean. But in we’ll just face it me being a geek, I started reading a lot of the research and what’s called the quantification of training, which is really an exploding area in exercise science simply because we now have all these tools that can record so much of our activity that didn’t exist even 20-30 years ago, that are allowing us to look at a workout session, look at an athlete in a way that we’ve never been able to do before. So, I started reading a lot of the history of this and it goes back to I think one of the pioneers they would say is a Dr. Eric Bannister, back in the 80s, who came up with something called TRIMP, which we’ll talk about in a minute. But one of the reasons that we’re really excited to have Dirk here is, I can tell you, when I read research, you very rarely see specific products mentioned, and when I’ve been reading all this, this quantification of training research, they keep mentioning TrainingPeaks, they mentioned training stress score, which is one of your inventions, and you really see just how much your tools have been part of this expanding field of quantifying the athlete. So, I think it’s an exploding area of science that you’re central to, so it’d be great to really delve into it with you.

Caley Fretz 03:13

Well, let’s start with a pretty broad question. I think that in cycling these days, people are all kind of aware that we have a lot more numbers to back up what people are doing than we did, even not that long ago. Obviously, the invention and then popularization of the power meter has changed a lot, but then also we know what to do with those power figures more so than we did even a decade ago. That brings up the question, is it good to turn athletes into numbers? Or do we get the Team Sky effect?

Dirk Friel 03:50

Is that a question for me?

Caley Fretz 03:51

Can be.

Turning Athletes Into Numbers

Dirk Friel 03:53

I don’t think at the end of the day that’s the point, I think really, at the end of the day, it comes down to your goals as an individual, or as a coach helping athletes prepare for, you know, to to attain their goals. If the goal is to complete the local Gran Fondo, and it’s your first event, certainly numbers don’t have to play a big part, really the number one thing there’s is frequency, just how many times do you bike ride and maybe how many hours a week you get out there and ride. But as you escalate that level of difficulty of achieving goals, you need to start looking out and finding new ways of achieving those goals, and it’s that art versus science of coaching. The more beginner of an athlete you are, the less of the pure science that you need. As you go up the categorization in cycling and you want to get to the next level, and now at the pro level, obviously every little kind of second counts, right? And so, at that point Why would you ignore numbers? If your goal is really to achieve a grand goal of podium in nationals, you just simply can’t do that off of feeling gut instinct, and certainly at one point you could, and that’s how it was done.

Caley Fretz 05:17

The old mercs ride lots, right?

Dirk Friel 05:19

Yeah. But you know, I always thought, if you have a grand goal, and you have tools available at your disposal, you get fewer and fewer excuses or more and more excuses, if you ignore the tools that you have at hand to help you in this day and age.

Trevor Connor 05:38

Not everyone loves the numbers. We caught up with retired Pro Tour Rider, Phil Gaiman believes very strongly in the importance of feel over metrics.

Phil Gaiman: Importance of Feel Over Metrics

Phil Gaiman 05:55

I think that the human body like everyone has their own cycles, and they’re never gonna understand. And there’s, there’s days that like, I should not have good legs, and I do, and there’s days that I should have good legs, and I don’t. And it’d be like, if you look at TFS, for example, I flew I did the Tour of Utah.

Trevor Connor 06:16

Yeah.

Phil Gaiman 06:17

That’s a high altitude, seven-day stage race, so I guess, I mean, I guess the proper thing to do would be to test your threshold based on the current altitude, and then the TSS would be accurate. But it’s, it’s, you know, when the altitude changes, it goes very smoothly with 3000 to 10000 feet, you’re kind of just guessing, you don’t really know what your threshold is, you don’t really know what you’re, but at the end of the week, you’re right, like we’re all, Lansky set his threshold to where he thought it was, and based on that it was his hardest week of the year, you know, including the Tour of California and Catalonia, all these World Tour races, you know, Tour de Suisse. For me, I didn’t adjust my threshold, so it basically looked like. so I’m just riding around zone two is what that but that’s not how it works, and then I flew straight from Salt Lake to Gerona, so now your time zones are off, that doesn’t go into TSS at all, it doesn’t TSS doesn’t know if you’re, if you’re waking up at 2am, or whatever. I don’t know, I’m a believer that all that stuff is bullshit, and you should learn your body, that’s, that’s where I’m going. I think just over the years, like Frank doesn’t need to tell me ride three hours at 270 watts, like, I know, my zone two is 270, like, I don’t need to be told, I if he says zone two, that’s I’m gonna ride what my zone two is, the altitude or whatever. So that’s, that takes a while to learn, that’s why I kind of think that power meters can be, they’re a tool for coaches, but they can sort of be a crutch for athletes. When back when I was coaching, if my athlete wanted to get a power meter right away, I’d say no, you need to learn what five minutes all out feels like without staring at a screen.

Caley Fretz 08:06

Your answer, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 08:10

Yeah, so looking at this from a coach perspective, and the first thing I will say is, I have probably spent an unhealthy amount of my life on WKO. I purchased it back when it was called Cycling Peaks in 2003, so that was its first year.

Caley Fretz 08:25

Yeah.

Trevor Connor 08:26

And I also just learned why it’s called WKO, because that’s what the files are called, and it stands for workout.

Caley Fretz 08:31

Right. Correct.

Trevor Connor 08:33

So this has been a great podcast for me. I’ve already learned things.

Caley Fretz 08:35

The history.

Trevor Connor 08:37

But I will tell you, as a coach, there’s is always that danger of getting too caught up in numbers, and it’s really important to keep it balanced. I think the numbers are critical, and you can tell a lot from it, but certainly with my athletes, when they send me their files, I’m always saying, send me descriptions. They are like, “Why do you want the descriptions you got the file?” I’m like, “no, I need to see the descriptions.” I’ve talked to other coaches about this they have all said the same thing, that even though the numbers are great, sometimes the way an athlete describes a ride can tell you more about whether they’re starting to push burnout than any number that you see. So it’s always key, use these numbers, they’re a fantastic tool, but also listen to yourself, listen to the way you’re talking. If you’re not sleeping well at night, if you’re getting grouchy with people, these are all the things that don’t we don’t necessarily quantify that also tell you a lot about your training.

Dirk Friel 09:30

Absolutely, absolutely. I mean, I’m by no means at all preaching that we should ignore, you know, the subjective feel of athlete and that rate of perceived exertion is so important. You might hit the numbers that were prescribed for you for the day, but did them in a horrible manner, and you felt horrible, and you just mentally barely got through it. There are certain workouts where that needs to occur, but that should not be the majority of your training. So, if you as a coach or self-coach, if you’re getting those senses, absolutely, the feeling the subjective side of training is is very important, and that how you react to the training mentally, leads into recovery, you know, how well do you recover from that workout? So, coaching by numbers is not painting by numbers, you know, and I don’t think we should all coach by numbers. And the way I look at it is, historically, we’ve been coaching maybe before power meters, we were coaching in a two-dimensional world, and now we have, my father always says, “It’s as if you couldn’t see very well, but you didn’t really know if she thought everybody else in the world saw the world like you do.” But you get your first pair of glasses, and you can now see half a mile and you can see the mountains and it’s

Caley Fretz 10:50

Suddenly trees have individual leaves.

Dirk Friel 10:52

Exactly, you see the individual leaves, and that is really what a power meter or numbers can bring to your world, is you quite literally, if you do not have a power meter, you’re seeing the world two dimensionally, and you don’t know the reason why behind certain things, but the power meter can give you that extra dimension. And maybe a little more knowledge around the reasonings, why certain things are occurring, and can give you in depth feedback on your limiters and where to spend more time.

Trevor Connor 11:24

But something I’ll add to that, so there’s often this perception that, hey, you have a power meter, you’re obsessing the numbers, you’re not really listening to how you feel, sometimes that really gets flipped around with athletes, I’ve seen a lot of athletes that they don’t have the numbers in front of them, they just go out and they ride hard. And you can tell them, when you go out and do an easy ride, now they still go out and they just hammer it and they pound it with their friends. There actually is a value as a coach to say to an athlete don’t break to 220 watts, when they send you the file, and it’s showing all these 800 watt segments you go, “that’s not what we discussed.”

Dirk Friel 11:58

Yeah, exactly. That’s the other benefit of just simply collecting the data. Again, historically, it was all about what are my numbers seeing right now this second, and there’s value in that, but I’ve always felt there’s immensely more power to the numbers, when you look at it over a long stretch of time, and you see the trends over time. That paints an absolute picture, which is unique to each individual athlete, and I’ve sat with professionals that come to me and they’ll actually have saved data, but they really haven’t looked at it through that lens of the trends over time, and when you can point things out to them, it might take them to a new level of performance.

Caley Fretz 12:39

That’s a fantastic segue into the pile of alphabet soup that we’ve written up on the board over here, which has all of the terms that Trevor wants to define, and it is important that we define these because the rest of the conversation is going to lean on these terms quite heavily. It’s a lot of acronyms, those who are familiar with power training, and particularly if you if you use pretty much any sort of software to to keep track of that training, you’re probably aware with at least the concepts, if not the exact acronym. Trevor, I think you wanted to start with what you called internal terms or internal factors, things like TRIMP, heart rate, rate of perceived exertion.

Internal Measures

Trevor Connor 13:20

Yeah. So why don’t we take a quick step back to the science and what you’re seeing in the research, they’ve really taken a lot of these metrics and broken them into two groups, which we’ve touched on, in past podcasts, this concept of internal measures versus external measures. So, we talked about and we podcasters, don’t throw out the heart rate strap.

Caley Fretz 13:41

Mm hmm.

Heart Rate

Trevor Connor 13:42

Heart rate and power are both very valuable, because there is a big difference between them, heart rate is what’s called an internal factor. Power is an external factor. So, an external factor is something that measures the work or the load that you did, but it doesn’t really tell you what’s going on internally. So, for example, you’re fitter than me, as I discovered when we are going up the Jamestown climb two days ago, if you and I are both riding at 220 watts. Yeah, it shows that that externally, we’re doing the same thing, but my internal response to that to 220 watts was I really wanted to pull over and throw up, while you are happy as can be in riding away from everybody. So, it was very different internal response. So it’s good to have both measures of what’s happening internally, and measures of what’s happening externally.

Dirk Friel 14:36

So, I think of these as input versus output, and can be very complicated or a simple way of thinking of it is your car, you’re given a gallon of gas and how far can you go with that gallon of gas, they have the input and the output, and from that you have a measure of economy. Do you have a big Ford pickup or the Prius? You know what I’m saying? You can train that you can train your economy. So, if you don’t know the input, you don’t know your economy, you’re only looking at the output, and those two very much relate to each other, and you can track that progress over time.

Rate of Perceived Exertion

Trevor Connor 15:15

I think that’s probably the most important message here is, and this is what I’m hearing from you is, it is the interrelation of these internal and external factors that’s so important, looking at how your heart rate responds to your power. And they talk in the research a lot about the uncoupling, whenever you see an uncoupling of the internal and the external, that’s often a sign of fatigue. So, if you’re going out one day, and you’re putting out a, let’s say, 200 watts, and you’re used to seeing 140 beats per minute, and all of a sudden you’re down at 120, and another internal measure that’s actually pretty good is what’s called rate of perceived exertion, and basically, you’re feeling like, wow, this hurts a lot more than 220 watts normally hurts. That’s a clear sign of fatigue.

Dirk Friel 16:01

Yep, yep. Yep, certainly, what I like to do with athletes is have a particular course that we can repeat, ideally, around the same temperature gradient, you know, in what I do locally in Boulder, certainly going up left hand, data benefit of that used to have the effect of altitude change as well. So, if I do James Town up or whatever, 90 minutes stretch of climb, I want to do, you know, we have that advantage here, I can track that over time and see the decoupling, and there’s actually an efficiency percentage that we have in in both TrainingPeaks and WKO, we have this decoupling factor, and you can track that over time. And so I really like to isolate it to particular workouts and go back and see that progress over time, and you can actually get insights into when you might want to change from the base period to the build period, because you’ve maximize your returns on that aerobic conditioning, and then it might give you some insights into like, you know, what I’ve really, I’ve come to the level of diminishing results in terms of that sort of training, and now it’s, it’s about time, and so it can give you some, I guess, more feedback as to when to might change up your, your training.

Trevor Connor 17:17

So, we’ve kind of jumped ahead of ourselves when we’re talking about how the internal and external metrics interrelate. But let’s take a step back and just look right now at the internal metrics, and really focus on what’s probably the most popular, or most effective of the internal measures now, which is heart rate. So, a few podcasts ago, we actually talked with Dr. Inigo San Milan about heart rate, he’s a big fan of using it in training. And what he likes about heart rate is that it actually correlates pretty well with lactate levels, or VO2, which are the gold standards for measuring that internal physiological response, problem is you can’t measure those out in the road, so as far as one when you’re out training, heart rates, the best internal measure that we got. And it’s been used for a long time, we certainly had heart rate monitors for a while before we had power meters.

TRIMP

Trevor Connor 18:19

We talked about Eric Bannister, so he created what was called TRIMP, which stands for training impulse. And it’s in many ways the grandfather of a lot of the or possibly most of the training metrics that we have now, TRIMP simply took the training load, which was the volume, how much time you spent, and multiplied it by the training intensity or strain, he used heart rate, so basically it was you took the length of the ride, you multiply it by the average heart rate, and you get a TRIMP score. That was later made more complex where they weighted it by intensity, so higher intensity training would have a bigger influence on the score than lower intensity training. My understanding is the TRIMP score is really the precursor for what you see in TrainingPeaks now, which is training stress score, TSS.

Dirk Friel 19:25

Certainly, Dr. Andy Coggan, you know, really took those concepts and expanded upon them and applied them to the world of cycling, the good and the bad of the heart rate, I’ll go into in terms of, you know, how I view them. Heart rate can in terms of the not so great about heart rate is it’s influenced by so many factors, the sleep, the stress, the caffeine that you ingested, you know, before the ride all effect heart rate, temperature, altitude, all kinds of stuff, right? So, you sort of have to have this little bit of a filter when you look at pure heart rate or comparing rides. Heart Rate also has a lag time, you know, you go out and do a 45 second, all out hundred percent effort, heart rate is not going to hit max heart rate but your power, you hit max power for 45 seconds it was absolute.

Caley Fretz 20:11

Trevor, there’s a whole bunch more, much more terms we want to talk about here. So, we have a lot of external measures. Well, thanks to the power meter, basically, I think that’s the primary difference, right? I’m seeing TSS, FTP, normalized power intensity factor? Why don’t we run through those real quick for everybody? Because I know we’re gonna be using them the rest of the conversation, and if you don’t know what those four things are, you’re gonna get pretty lost pretty quickly.

External Measures

Trevor Connor 20:36

Yeah, and I think that’s really what I hope we offer to all our listeners today is what these mean, because you hear them at the group rides, and a lot of people don’t fully understand, and so I think we’ll just with the internals, the key measures were the TRIMP, heart rate, and rate of perceived exertion. So, with that, let’s start with I think one of the biggest and most valuable the external measures is the training stress score.

Dirk Friel 21:04

Yeah, certainly. And even before that, you can’t get there without functional threshold power.

Trevor Connor 21:08

Right. Good point. So, let’s start there.

Functional Threshold Power

Dirk Friel 21:10

Yeah. Well, I’m glad to hear people are talking about it on the group rides, because it used to not be like that, it used to be, “Hey, would you do yesterday in four-and-a-half hours?” Okay, well, great. All right, well, you know, next level of that was I have an SRM, Oh, I did 4500 KJ, all right, well, great, well, I like to make the comparison than if I and, you know, weigh the same, and we both ride at 250 watts, for four hours, it’s going to have a lot more effect on me than him, his threshold is so much higher. So that, you know, that gets to TSS and FTP. But functional threshold power, at its simplest definition, let’s say it’s what you can do for an hour, an all-out 100% effort for an hour. Now, through software and through WKO4, we now have a power duration curve metrics, and we now model your functional threshold power. So, every new ride that you do data comes in, we actually rerun the curve, and your FTP might actually change a little bit up or down. So that’s at the core, all these advanced metrics is really that threshold power, and, and really kind of that energy system change. And you could get to it by going to a lab and testing and getting those lab results as well, but getting that one number, knowing that it isn’t an absolute, this changes, it can change day to day simply based on your sleep quality and stress level, etc., how fresh you are.

Trevor Connor 22:47

At the center of this is FTP, but I’ve heard that criticism of FTP, will functional threshold power this this one-hour power doesn’t match up perfectly with anything that’s going on physiologically, so so how come you landed on FTP versus a different metric?

Dirk Friel 23:06

Yeah, I think early on, it was a practical way to get to a value without, you know, we didn’t have the software to actually do a modeling for you like we do now. Or fine, you can go to the lab and pay the money and find that ventilatory threshold out for yourself and plug that in. But certainly, I absolutely agree it’s not one hour for every single person, it was a very practical way to help educate people, number one, as to why you would even have this concept in the first place, and then how could they do a field test? One hour is very difficult. So, it became a 20 or 30 minute field test, and subtract 5% from there to estimate your functional threshold power. But quite simply, you it was a real practical way to get it out to the masses, and then from there, you can educate people, and now the software itself will fine tune it to the individual based on your own unique power duration curve, I would say let’s say Cavendish and Wiggins, they might have the same functional threshold power, but their curves are very unique, ones a sprinter one is this stage race climber, and that gets into the even newer science now of looking at those phenotypes and the curve, your unique curve, your power duration curve and how training affects you as an as an individual.

Trevor Connor 24:29

We all agree that a lab test at threshold is best, but that isn’t always possible. So, we caught up with the Dr. Inigo San Milan, arguably one of the best cycling physiologist in the world to get his thoughts on FTP and how to find the best number for you.

Dr. Inigo San Milan: FTP and Finding the Best Personal Number

Inigo San Milan 24:48

I believe that it’s not just about what, with FTP, you have to take into account heart rate as well. Heart rate is a it’s a truly a physiological parameter, right? And heart rate directly reads percentage, what what happened to the body? Right? Now what it doesn’t represent, necessarily, what happens with the body, you can be, you know, like thinking that your FTP, let’s say 325 watts, right? But actually, you know might be different, you might see that heart rate keeps going up going up going up or not, because you’re getting more and more medical trends, we know very well in the lab that the lactate response directly correlates with the heart rate, they do seem would be to train with a lactate mirror, right? In the meantime, we need to translate those metabolic responses into something that we can use in a database. So that’s where heart rate is a great parameter still, it’s not old school at all, It’s a truly physiological parameter.

Trevor Connor 25:53

So, you mentioned FTP, or functional threshold, so what exactly is functional threshold, and what would be a good way to test that out on the road?

Inigo San Milan 26:13

Maximum power output status state, or states that you can sustain for a given effort, I don’t see this very scientific, to be honest, that term, like, as good as you could get for maybe something outside the laboratory, but that’s a game where I’m throwing the heart rate, because the heart rate, you know, you want to go for an effort, when you have as much as on metabolic sustainability or steady state, right? And that’s where you can look at the heart rate as well, and combine it, for example, you may say like, “Oh, I’m gonna give it a shot, and I think my FTP is 40 minutes for, you know, 325 watts.” But you see that a 325 watt, in minute five, it’s, let’s say, 175 beats per minute, in minute 10, it’s 185, in minute 7-12, already 100, so you know that that’s not a metabolic effort. It is now you truly FTP, because you cannot sustain it. So, you, you know, and therefore, eventually, what’s going to happen, people are going to drop the power output in their performance, because they haven’t dialed that it.

Trevor Connor 27:31

So those commonly held concept of, go do a 20-minute time trial all out, then take your your power, multiply it by 95%, and you’ve got your threshold. It sounds like you’re saying that’s overly simplistic?

Inigo San Milan 28:01

It or that some people might in some people they might not, I think it’s over simplistic, being steady, but you have to push it to the limit, you’re not steady anymore, right?

Trevor Connor 28:12

Right.

Inigo San Milan 28:13

It’s about trial and error, you have to find your own pace, right? And yeah, and they push to much the power output, that’s going to increase the metabolic stress significantly, and they cannot afford it because they don’t have a good lactic capacity, it’s going to come back to haunt them and eventually decrease the power.

Caley Fretz 28:34

Speaking as the sort of residents power Luddite in this room right now, how much does this matter? I mean, how much does this the difference between these different metrics? The difference between these four metrics is probably relatively small, right? And we were saying that FTP is going to change day to day anyway, I mean, at the end of the day, as much as we attempt to quantify training, it is essentially impossible to completely perfectly quantify what we’re actually doing, right?

Trevor Connor 29:05

So, if you remember, we had Rob Pickles in here a few episodes ago, who he spent his he spent years in the lab testing people, and if you tried to use maximal lactate steady state VT2 and FTP interchangeably, he’d probably jump up and down and yell and scream and storm out of the room. I’ve had all mine tested I’ve had a lot of my athletes tested, and the reality is, often you’re talking a five-watt difference, it’s not that huge. The biggest thing I always tell my athletes is to change their perspective on FTP, a lot of people get caught up into “Well, that’s a measure of how good I am, so the higher the number, the better,” and they do all these tricks to if they test themselves to try to come up with the biggest number they can. The biggest mistake I see people make is they go oh, well, I can do a 20 minute test to find my FTP, and I’ll just skip that little part for you subtract 5%, because I like this number better, it is really important to find a number, an accurate number versus the highest number, because you’re using it for training, you’re using it for these metrics, and if your FTP is say, 280, and you plugged 320 into whatever software you’re using, you’re going to get a lot of bad information that’s going to overtrain you. I just took on an athlete who did that, his FTP was 40 watts too high, he trained for about a month of November, burnt out how to take three weeks off, went back at it in December, burnt out again, he finally came to me, he’s like, “I need a coach, something’s going wrong here.” And I tested him and went, “you have your FTP 40 watts to high,” went back, adjusted everything to the correct FTP, and he had been training completely wrong been training way too hard.

Training Stress Score

Dirk Friel 30:54

That leads into the training stress score. Once we have your functional threshold power, and a new ride file comes in, really the first thing done is we find your intensity factor. So, if you did a one hour ride at threshold, you would have an IF of one, or most people do not, they don’t do workouts at an intensity factor of one or above. Probably the majority of workouts are done at a higher level, right? Exactly. So roughly speaking, you know, most of your training is around 60-70% or so of threshold, simply because you can’t ride at threshold by definition for all of your training rides. And once we have the intensity factor that is more or less multiplied by the duration of the ride to come up with a training stress score. It’s a nice number, whereby you can quantify that ride, so even though Jens Voigt and I have different thresholds, we weigh the same, and we rode it 250 watts for four hours, our TSS values will be dramatically different, his intensity factor was much lower than mine, and hence his training stress score value will be lower, and mine will be higher, then he and I can actually compare each other’s rides and kind of normalize it if you will.

Trevor Connor 32:18

We had a chance to talk with Aqua Blue Sport Pro Tour rider Larry Warbasse, who believes strongly in a balance between numbers and feel. He had a few things to say about TSS.

Larry Warbasse: TSS and Balance Between Numbers and Feel

Larry Warbasse 32:30

TSS is how hard the day was, and I know like the exact definition is like, 100 TSS equals one hour at threshold. I guess TSS is the one that I would pay most attention to of all those, TSS to me seems almost like the most accurate way to quantify the training, but then again, and I don’t know the exact details of this, but I’ve heard there are some arguments to say like TSS isn’t necessarily the be all end all, because you can go do a two-hour ride that’s super intense, and get like 200 TSS, or something say, whereas like you can go do a six-hour ride, where you just riding, and you’ll have like 120 TSS, and like those have totally different effects on the body, and just because you did two hours all out, doesn’t necessarily mean it was harder than riding six hours. I definitely think it’s a pretty good, pretty good indicator and a good thing to follow.

Caley Fretz 33:29

Fast Talk is sponsored by Quarq, maker of next generation power meters, including the SRAM XX1 Eagle power meter, the XX1 power meter, unites Quarq’s Dzero platform with carbon Toon crank arms for robust, intuitive power measurement, in the lighest ever mountain bike chassis. It’s compatible with all of SRAM’s one by mountain bike drive trains, find out more at quarq.com/dzero.

Dirk Friel 33:55

Sometimes a loss of FTP can be beneficial, you know, we now have newer metrics like functional reserve capacity, FRC, which is really measuring the amount of energy you have above threshold, so for criterium racing, cyclo-cross, like these short hard bursts, if you’re training that that can actually bring your FTP down. At the end of the day, that might be okay, you get to a sufficient enough level with your, your threshold power, that now you need to focus on the race intensity stuff, the FTP might suffer, but you’re going to gain in functional reserve capacity and have a better sprint at the end. If all we had to do is measure your FTP to get race results, it doesn’t work that way, right? Almost opposite of FRC is stamina, your ability to ward off fatigue even, you know, past an hour.

Caley Fretz 34:46

Right. And we,

Dirk Friel 34:47

That’s a goal for Gran Fondo for Iron Man.

Performance Management Chart

Trevor Connor 34:50

Alright, so we just threw a whole bunch of definitions at you, and now we’re going to look at a little higher level because you can take all these different bits have information, and what we really want to see is the trends in you as as an athlete. And so in the science, they talk about this as a systems based model or impulse response, we’ll leave those terms aside, what you called and TrainingPeaks is the Performance Management Chart, and you’ll see most of the software out there, if you go golden cheat, or any of the other tools, they have some sort of variation on this, where we’re trying to ultimately see how you’re going to perform, or come up with some sort of estimate of how you’re going to perform. And again, this was, Bannister was one of the first ones to come up with this, and said, “really, your performance is based on this relationship between your fitness and fatigue.” So, if you have really high fitness, but you’re also really fatigued, you’re actually not going to perform that well, or if you have decent fitness, but your fatigue is low, you might actually perform a little better. So, we really want to see the interrelations to define your ultimate performance level, and that seems to become the basis of this performance management chart that shows you an overview of your season and hopefully where you’re at.

Dirk Friel 36:15

Absolutely, it truly paints a picture of that unique individuals training program over time, and it is really exciting when you get a lot of data from somebody, they have a lot of files, they sync over from Garmin Connect or whatever, and you can just spot the trends, and kind of teach them a little more about what they’ve been doing. And it’s like, it gives them a lot of insights, you know, if we dig into some terms, people will hear, CTL, or chronic training load, we really kind of referenced that as being your fitness, and your fitness over time. Unfortunately, you need 42 days-worth of files to really make that accurate, once you start out in TrainingPeaks, and you’re uploading your files, after five days, you see this blue line going up, and it’s called your chronic training load. Keep in mind, it takes a while just like it takes a while to build fitness, it’s all based around research of you know, aerobic conditioning, etc. So, we look at our default is 42 days, is it’s an exponentially weighted rolling average. So, the training you did seven days ago, will affect this number more than the training you did 21 days ago, around 42 days is when it starts to get more accurate. So now that you have this fitness CTL at the same time, we have this kind of magenta looking line that that’s acute training load, and we refer to that as your fatigue. And you know, you can’t gain, in order to improve in any sport, you have to stress the system, you recover, and you let that kind of fitness shine through. So, if you go into a training camp, for example, and you do a really hard week, you’re going to come out with of that with higher fitness, but you will have much, much greater fatigue will have been built up during that training camp. So intuitively, you would not have a race, if the camp ended on Sunday, you not have your important race on Monday, right? The next day, even though your fitness by definition is higher, your fatigue will be really high as well, and so I think we all intuitively understand that, and even if you’re a self-coached athlete, you’re managing your fitness, fatigue, and form. So, form is simply the difference between the chronic training load and the acute training load, you know, or the fitness and the fatigue, as you mentioned, you can have high fitness but if the fatigue is higher than your fitness, your form is going to be pretty bad. So, somebody can beat you, even if they have lower fitness level than you, if they are fresher, if they have lower fatigue, they can take advantage of you on you know on the road and get away from you right at the last second and win the race. So, this is as I mentioned earlier, this is really a picture that’s painted through your training, and every single individual athletes PMC performance management chart, looks different. And there’s no secret numbers that you’re really trying to hit, it’s more or less about you comparing against your own past history and trying to find insights that can make your training more valuable. I like to say I mean everybody intuitively, does it, they may not be quantifying it, fitness, fatigue, and form. That’s what we’re trying to manage to prepare for an event.

Caley Fretz 39:44

I think this is one of the major, you have to be careful, to be very, very careful with these things, not to try to compare yourself directly to other athletes, and I think that that is that is definitely well, athletes are competitive, right? They want to compare themselves both on and off the bike, but in a race and online, you know, I definitely seen people post these kind of numbers, “Oh, my CTL is this, Oh, I must be flying right now my CTL is 140,” whatever, someone else’s at 110. Maybe that person is actually faster.

Caley Fretz 40:19

Right.

Dirk Friel 40:19

There are ranges.

Dirk Friel 40:20

That you probably need to be within to have logical guesses, you know, you can’t be a competitive Category One rider, with a chronic training load of 30.

Caley Fretz 40:32

Yeah, that’d be, you know, my attempt.

Dirk Friel 40:34

You might take some time off, you know, but continuously and consistently be a very top competitor, you must be in a certain range, and those ranges overlap amongst the categories, right?

Caley Fretz 40:45

Right?

Chronic Training Load Individual Variability

Trevor Connor 40:46

And this is something I’ve seen, and I’ve talked to other coaches who have seen this as well, that anytime an athlete gets into CTL hunting, so we have all these different things you can hunt, but there’s certainly CTL hunting, of the higher I get my CTL, the faster and stronger I’m going to be, what I have seen is, there’s actually an optimal range for each athlete. For some, it’s higher, for some, it’s lower, but as you learn your athletes, you’ll very quickly discover with one athlete, if he or she gets over 120, they’re in trouble, where you have another athlete, and if they’re not over 120, they’re just not fit yet, everybody’s a little bit different. So, it’s important thing to know about each individual.

Dirk Friel 41:30

Yeah, and I mentioned that it’s the same for training stress balance, which is the form, you know, you we see veteran Tour de France athletes, they can handle the third week of the tour, because they’ve built up those years of resilience and stamina, and they can be in a negative state in the third week of negative 80, or whatever it might be training stress balance, whereas, you know, a rookie first Grand Tour rider, hitting those numbers can literally crack them for the rest of the year. Yeah, it is a very unique picture for each individual.

Trevor Connor 42:04

Yeah, I’m at negative 100 as of this morning.

Dirk Friel 42:08

I’m at 80, you know, you’ve done a lot more than me, but lately.

Trevor Connor 42:13

I don’t train anymore. I don’t get out to Colorado very much, so I might have not.

Dirk Friel 42:19

Trainer rides.

Trevor Connor 42:20

Well, I always tell my athletes don’t do what I do. Because I’m an idiot and I need a coach.

Dirk Friel 42:25

Do as I say.

Trevor Connor 42:26

Yes, exactly. Or it’s the good old every coach needs a coach. But yeah, I had five days in Colorado, boy did I take advantage of it. This is a classic example, my CTL line just shot way up, but that measure of fatigue is up at 177, and I can tell you I was this morning, going up a pretty easy climb, that’s usually a recovery ride for me, going, “I don’t remember it being this hard.”

Dirk Friel 42:52

Yeah, something that just popped in my mind, is we also have TSS based around heart rate, cyclists do have other bikes, so you can afford a power meter for every bike, you can have just simply heart rate on for a workout, or you do a run, or hike, or whatever it might be in the offseason, we do calculate TSS based simply on a heart rate as well. But we have to have a more or less an accurate threshold heart rate as well. The goal of heart rate is not to have higher heart rates, you know, right, the goal is not to increase your threshold heart rate or input, but to increase the output or the wattage I can get out of that input, right?

Trevor Connor 43:33

No matter how fit you are your threshold heart rate is your threshold heart rate, and it only just goes down with it.

Dirk Friel 43:41

I’m experiencing that. Absolutely.

Trevor Connor 43:46

That being said, there’s is also a huge there’s a tangent, but there’s huge amount of individual variability. I coached a woman who was young, and a top Pro, she was over in Europe, and her endurance pace, If she went out and did a four-or-five hour endurance ride, she’d be at about a 95 heart rate, I don’t think I ever saw her break 150.

Dirk Friel 44:11

Mm hmm. So everybody’s different you know in person. Yeah.

Caley Fretz 44:16

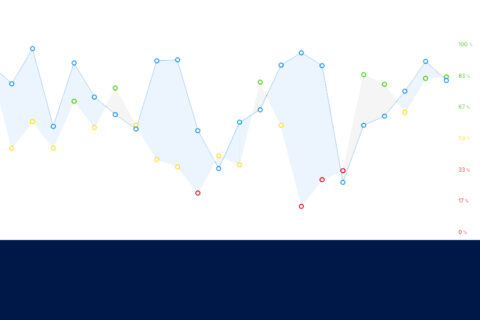

So if all of this is making your head spin a little bit, a visual might help. We’re going to put a performance management chart, a sample maybe we’ll take Trevor’s, will take Trevor’s from his week here in Colorado.

Trevor Connor 44:27

Don’t do anything you see on it.

Caley Fretz 44:30

We’re gonna take Trevor’s and we’re gonna tell you not to do it, and put it up on on Velonews.com, along with this podcast. So if you access this podcast via iTunes in your phone, or something like that, you’re gonna have to go use probably the google machine and find the actual page where we hide this podcast on Velonews.com. It will be up there.

Trevor Connor 44:49

Before we talk about what numbers we think are valuable for training, let’s hear again from Larry. He had a few things to say about the performance management chart and a metric we barely touched on, training zones.

Larry Warbasse: Performance Management Chart and Training Zones

Larry Warbasse 45:01

I think you don’t want your TSP to get too far down there, I don’t know, I guess like the CTL, I’ve seen all over the place, and I’ve performed well all over the place with the CTL. So, it’s hard for me to say whether, what is useful about it, you know, I guess it’s just a good, good guideline, but I don’t think it’s, again, the be all end all. And I also think, like, say, at the end of the season, you’re a lot more fatigued than you are the beginning, so maybe, whereas at the beginning of the year, you could perform with a really high CTL, maybe at the end of the year, you need to be lower, to perform just as well, most, most of the numbers are pretty important. And I guess it just depends, what I guess what you’re doing. So, I guess, for me, using this, I mean, just zones in general, are pretty helpful. So, I think my coach, and I work with something like seven zones, I’m not 100% sure, is bad, considering I’m saying that they’re so important, but you know, I guess being aware of your zones, and being inside of whatever the zone that you’re supposed to be in is really important. So that goes for recovery, that don’t go too hard on recovery day, I think that’s huge, then, you know, it’s like, different zones, make different adaptations. So I think it’s really important to know what your zones are, and what zone you’re in, at the moment, versus what zone you’re supposed to be in, because I was even talking to my coach about this, and a guy he was working with, was saying, you know, if you’re always on the high end of your zone, you’re almost not really in your zone, you know, like, like the center of the zone, surely you are working that system that you’re supposed to be working in that zone. But things can change little by little every day, even you know, your threshold can even change a little bit each day, so if you’re on the super high end of one zone, or super low end of the other zone, you might be in a totally different zone.

Caley Fretz 47:05

The last thing we want to do today is provide a little bit of just practical guidance and advice because a lot of this, it’s useful information, but more from a 10,000-foot view, and how you want to use these various metrics, and the way that you want to think about your training. Let’s talk about something very practical. I want to start with what figures are on your Garmin or whatever computer you’re using. I think Garmin is kind of like Kleenex at this point, it’s become the brand name for a cycling computer, but anyway, what is on your cycling computer, what metrics on your side computer when you’re out on a training ride. Let’s start with Dirk.

Figures to Examine on Cycling Computers

Dirk Friel 47:47

Yeah, I have multiple screens, depending on what I’m doing, where I’m at in the ride, I love having an interval screen, where I can see I hit the lap button, I’ve started the interval, I now have, time, I don’t really do intervals based off distance. So, I don’t I kind of like bigger numbers, so I won’t have a distance on my interval screen, but I’ll certainly have time, current watts, and I really do like a three second averaging.

Caley Fretz 48:16

Do you do a longer average for climbing?

Dirk Friel 48:19

No, I just sort of set it to like 10 seconds, 30 seconds, because I just sort of,

Caley Fretz 48:26

Yeah, I can definitely see why you do that. I put mine at three seconds, so it’s a little smoother, and then I see an accumulated normalized power for the interval I’m doing now, so I can see where I’m at, and I so I know the target of the interval, and it gives me immediate feedback during the interval, the lap button to stop it. And then the overall screen just giving me time, distance, TSS, normalized power for the ride so far. And you know, around here, I definitely like having altitude gain. Yeah. What about you, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 49:04

So you getting yourself in trouble asking me this question, because I just got a new bike computer and I discovered the custom data screens.

Caley Fretz 49:10

Oh, yes.

Trevor Connor 49:10

So I’m doing all right now my favorite is translates my ride into the number of slices of pizza I can eat.

Dirk Friel 49:18

Oh, the IQ app.

Trevor Connor 49:20

Oh, yeah. That’s a good one.

Caley Fretz 49:22

That’s all I look at. Wait till I get two pieces then go home.

Trevor Connor 49:25

Really rewarding.

Caley Fretz 49:26

Motivational.

Trevor Connor 49:27

It’s fantastic. I wanted to quit my ride today, they have a beer as well, but the pizza was one that motivated me today, because I was ready to turn around after 10 minutes, and I looked down like I haven’t even rode a slice of pizza. But yeah, so really important thing that you’re kind of implying here is, what you look at on the screen when you’re riding, what you look at after the ride should be different things. There are all sorts of things that you can use, but really at the end of the day, I look at the three basics which is heart rate, power, and cadence. And depending on what I’m doing, I focus on one or the other, I certainly I don’t look at straight power, if you look at power, real time, it’s all over the place. So, either use a use some sort of averaging with it, I frankly, look mostly at a thirty second power averaging, but at least a three second or a 10 second.

Caley Fretz 50:22

It’s because your three second and thirty second power are the same thing, Trevor.

Trevor Connor 50:25

Always.

Trevor Connor 50:27

But when I’m going out for a long ride, a long, more steady ride, I’m really going to focus on heart rate, simply because you’re going to fatigue, muscle fibers aren’t going to work as well as they used to work, so by the end of the ride, you’re recruiting more muscle fibers to produce the same power, what all this means is at the start of a five-hour ride, 200 watts is very manageable, at the end of a five hour ride that 200 watts might start getting pretty hard. So that’s again, looking at the talking about this external side. So I really on a long ride like that, want to see the internal factors, and I’m going to focus more on staying at the same heart rate across a long ride. When I’m doing interval work, very intense work, for shorter periods of time, I’m going to focus a lot more on wattage.

Dirk Friel 51:17

Yeah, and I’ll add on to that, that I think more in the early season is when I focus on a heart rate.

Trevor Connor 51:22

Right.

Dirk Friel 51:22

And as you get closer to the race season is when emphasis really tends to switch more towards power. So, I absolutely agree that all heart rate within the interval session to track that as well, and, for a lot of writers cadence is very, very important, because that’s their limiter, they can’t do 100 RPM for even five minutes. So for some folks that have concentrate on that having that within their output, or right there on their handlebars can be very valuable feedback.

Caley Fretz 51:57

I usually don’t ride with a computer anymore. So, I’m not going to answer this question.

Dirk Friel 52:02

You know, there’s also those days too where, you know, hey, we’re trying to work on pacing, and so I want you to think, I want you to go out and do 250 watts for 20 minutes, and tape over your Garmin, so you can’t see it, and then let’s look afterwards and see how close you were to that, because we are trying to train the internal clock and internal pacing, and the numbers aren’t going to tell you your energy reserves on that day, and when you’re in the race, you have to have that internal kind of like senses, and we can hopefully train that during training.

Trevor Connor 52:40

The other thing I’m going to add to this, is also know that the type of rider you are. I am a bit of a data geek, but I’m still gonna generally train right. So, I do have TSS, and I have left right balance, and normalized power, all the different metrics on my screen, and I can look at them and go, “hey, that’s kind of neat.” If you are one of those people that chases numbers, be careful about having too many things on your screen that are going to make you forget about what you’re supposed to be doing on the training ride and try to generate that big number.

Caley Fretz 53:12

I used to do that sometimes, I’d get to get near the end of a ride and average power would be like, right near 250 or something, and I just like start riding really hard for no reason, just because I wanted to put it over 250 for absolutely no good reason.

Dirk Friel 53:25

Yeah.

Caley Fretz 53:25

I was definitely one of those people.

Dirk Friel 53:28

At the end of the day, it’s about what’s the intent of the ride? am I achieving that original intent, with or without numbers? And if you’re not a numbers person, my suggestion is get it saved, get it stored, you can go back and look at it, and learn from it, or hire somebody do a one hour consultation, the local coach, and kind of get some feedback from them on what they’re seeing on the numbers, ask them questions. You don’t have to be the expert, you know, just, but if you have the data, then experts can do a better job of helping you out.

Caley Fretz 54:01

Which brings us to our final question of the day, which is and I think we could do an entire podcast on this and we sort of just have actually, we’ll just we’ll narrow it down a little bit. What are the first couple things that you look at after a ride? When you’ve uploaded everything, you’re taking a look, what are you trying to figure out? Is it how hard was that? What are the primary concerns when you’re when you first upload and take a look on a laptop?

What Data Is Important To Look At After a Ride?

Dirk Friel 54:27

Again, the intent of the ride. If it was an easy prescribed day, or I knew it should have been easy, did it fit the bill? Or if we were doing a very structured day, if I just simply look at it, visually without the absolute numbers, but visually, does it reflect what I had anticipated or what I prescribed as a coach? Even before looking at it, just looking at the TSS, the time, do those reflect the intent of the day? The next level is, you know, I visually will look at it and see if it matches what I expected it to look like, based upon the prescribed workout, and then from there, I might be like, “Well, okay, this was a hard day, it was really meant to push the envelope, how close did we get to some of our peak performances historically?” Is it a top 10, is a top 5? The aim is not to set a new peak performance every week, you know, and you simply can’t, but are the trends going in the right direction? Sometimes I’ll pull that data out and see how it compares over time, depending on the athlete, what duration I’m looking at, is a 12 second sprint, or is it a 90-minute endurance, you know, zone three effort?

Caley Fretz 55:47

Trevor?

Trevor Connor 55:49

When my athletes send me their files, I have basically an order in which I look at things. So, I do start initially with the ride, and the first screen I look at, I have two graphs, both showed their training zones colored, and I look at their heart rate, and I look at their power within the zones, to see how well they executed the ride, were they training in the correct ranges or zones, or were they all over the place? And obviously everybody has to have a little fun, and you shouldn’t be sitting there in a ride staring at whether you’re in the right zone or not. But there’s a difference between that and when you tell an athlete, okay, so using zone numbers, which I’m actually not a huge fan of, it’ll just go with the terminology, you tell somebody to go out and do a zone one ride, and you see half of the ride up in zone three and four, you know that that wasn’t a very well executed ride, and they’re a little bit off track. The other things that I will initially look for in the rides is what we were talking about in that that uncoupling of the heart rate and power. So, I look for cardiac drift in the ride, especially longer rides, and that’s where, let’s say you started the ride at 130 beats per minute and 200 watts, if you’re at the end of the ride, and now at 130 beats per minute, you’re doing 120 watts, that’s a lot of cardiac drift. That’s either fatigue or dehydration, but it’s a sign that, boys that ride did something to you. Then I immediately step back and look more for the trends. So, over the course of the week, how’s their heart rate and power distribution? Are they in somewhat the right ranges? As you know, I’m a big fan of Sieler’s polarized approach, which is really that you should have 80% of your time at low intensity, 15-20% of your time at high intensity, and actually in cycling and finding more and more, you need probably 10% of your time in that middle, so I look for that sort of distribution, I look at that performance management chart to see how they’re trending, where’s their fatigue at? All those various signs just to see, where’s this athlete going? What’s going on with them right now?

Dirk Friel 57:59

Relative to goal.

Trevor Connor 58:00

Yep. Right. Yeah, so that’s also really important with all my athletes every week, I say, “here’s the goals of the week,” I actually talk about in terms of purpose, I give them the purpose for the week, and success or failure of the week, I always tell my athletes, I’ll give you workouts to do, I’ll give you a volume goal, but here’s the thing, if you meet the volume, you do all the workouts, but you fail on the purpose of the week, then it was a failed week. If you achieve the purpose of the week, but you don’t get the volume, you don’t get all the workouts, I still consider a successful week.

Caley Fretz 58:33

Yeah. Yeah. You agree?

Dirk Friel 58:35

Yeah, definitely. And referring to the goal also means how many weeks are we away from the A priority event? As you get closer, I think that definition of success of the week needs to get tightened up, more and more things become more and more important as you get closer to the race. So, it’s kind of in relation to the goal or the time frame, we’re talking about, how many more weeks do we have or days to the important race? Clearness of the purpose of the day becomes much, much more evident and necessary, the more defined the goal is, absolutely. Then you can compare the delta between where am I at today? Where do I need to be, what are my limiters? Not every weakness is a limiter, but it’s a weakness is a limiter, if it’s holding you back from success in that upcoming goal, you know, that that race. So, let’s look at the demands of the race, ideally, we have past years data from races, and then we can see where we faltered, and then make up for that in turning going forward.

Caley Fretz 59:45

Dirk, thanks for coming.

Dirk Friel 59:47

Absolutely. Thanks for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Caley Fretz 59:50

There you have it, all of the myriad ways to quantify your training. I think we’ve covered that quite exhaustively, although this is a subject that we will I’m sure returned to, I just said exhaustively, and Trevor shook his head, So there’s apparently there’s more, there’s more in there somewhere.

Caley Fretz 1:00:10

That was another episode of Fast Talk, as always, we would love your feedback, email us at webletters@competitivegroup.com. Subscribe to Fast Talk on iTunes, Stitcher, SoundCloud, and Google Play, be sure to leave us a rating and a comment while you’re there, and also while you’re there, check out our sister podcast, the VeloNews podcast, which I am also on. That covers news about the week in cycling and you could hear me on that podcast as well. Become a fan of Fast Talk on facebook, at facebook.com/velonews, and on twitter at twitter.com/velonews. Fast Talk is produced by VeloNews, which is owned by Competitive Group. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. I’m Caley Fretz, here for Trevor Connor and Dirk Friel this week. Thanks for listening.