Here to unpack the duality of data and intuition in endurance athletics is cycling coach and former pro cyclist, Julie Young. She and Colby unpack some of the struggles they each faced in their earlier racing careers around doping in the sport.

The main focus of this conversation is to understand the helpful and healthy place for data and analysis in your training. Learning to craft your own intuition is something that, when paired with the right amount of data, can lead you to becoming your best athletic self.

REFERENCES

Julie Young: https://julieyoungtraining.com/meet-julie/

The Rider: https://www.amazon.com/Rider-Tim-Krabbé/dp/1582342903

Episode Transcript

Julie Young 00:00

One thing I think I love about the mass start racing is like, I would never race as hard. Take my game to such a high level without my fellow competitors. And that’s the thing I really appreciate about and still do, like I do love. Mass start racing is such an opportunity to learn on so many levels. And it’s really the fellow your fellow competitors that help you take your game to that next level, and learn on so many levels. And so that’s how I saw it more like I again, I didn’t see it as like, I wanted to beat these people. I just it was like this opportunity. Like they push you to this point where you were able to learn so much more about yourself. Yes. And that’s really what I appreciated about it.

00:59

Welcome to the cycling and alignment podcast, an examination of cycling as a practice and dialogue about the integration of sport and right relationship to your life.

Colby Pearce 01:11

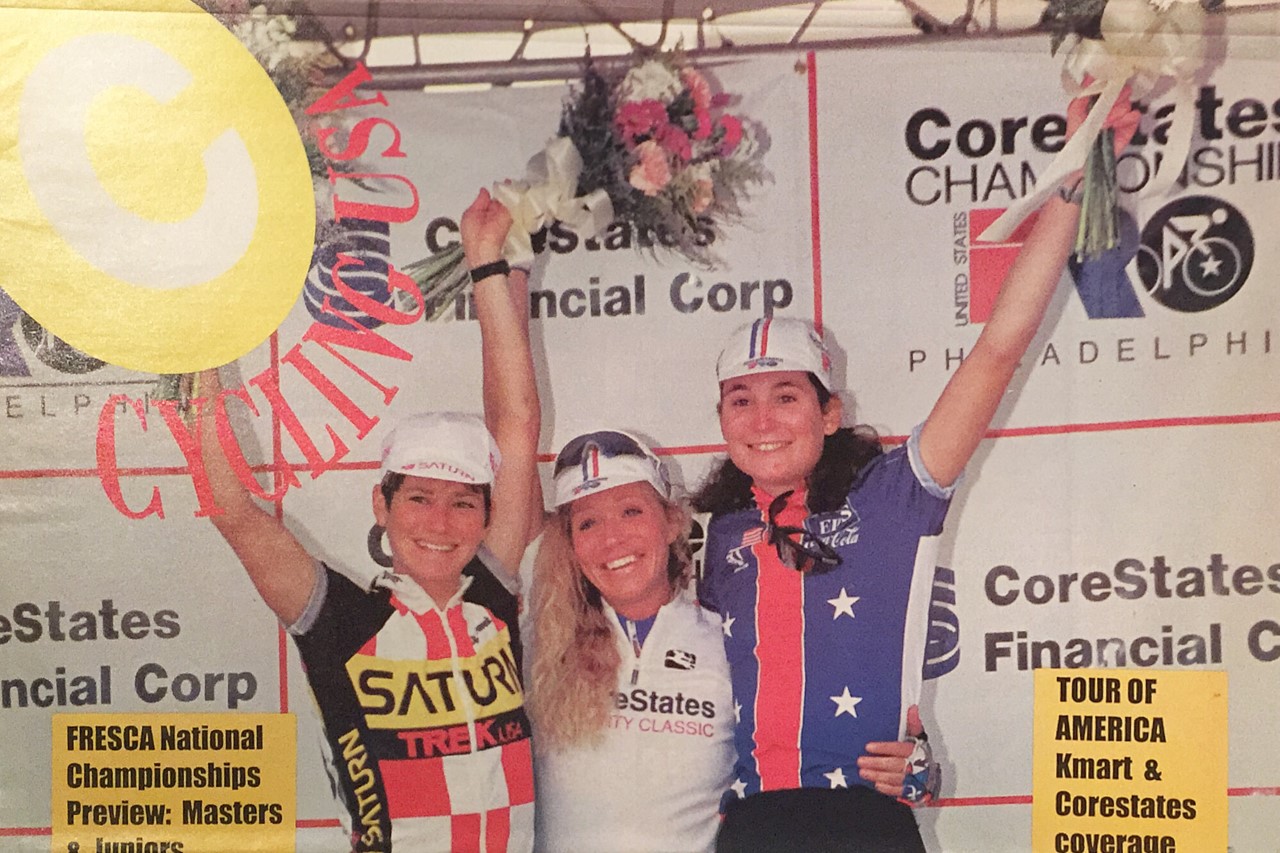

Greetings and salutations, cyclists, athletes and humans. Thank you for joining me for another episode of the cycling and alignment podcast. Today’s guest is none other than the amazing Julie Young. Julie is a coach. She’s currently pursuing her master’s in exercise science, and works as the sports science specialist at the Kaiser Sports Medicine Endurance lab. She’s also a former professional racer, and in 1992, she won the Tour de L’Aude, which at the time was considered the women’s Tour de France.

Colby Pearce 01:47

In today’s conversation, we talked about the evolution of her career as an athlete. How she was driven to race in Europe and found it incredibly challenging and rewarding at the same time. She speaks about her motivations for racing, and what drives her as an athlete.

Colby Pearce 02:05

We also have a very honest conversation about racing in a peloton where both of us knew our colleagues were doping at the time and how we handled that reality.

Colby Pearce 02:18

I plan to talk to Julie more about the duality between the data of coaching and the instinct or intangible elements of coaching athletes. But we were faced with some time constraints. And so I had to cut the interview a bit short before I got to unpack everything that I wanted to in our discussion. Perhaps I can invite her back on the show in the future and we can have another round, because I think she has a lot of interesting perspectives and good things to say on this particular part of the conversation.

Colby Pearce 02:52

One aspect she does touch on during today’s discourse is the fact that she believes that cycling is fallen culturally into a bit of data worship. That’s the term she use and I would have to agree with her.

Colby Pearce 03:09

Without further prognostication, please enjoy my discussion with Julie.

Julie Young’s competitive cyclist background

Colby Pearce 03:18

Julie, tell us a little bit if you would about your background as a competitive cyclist, how did you get started racing? How old were you? What inspired you to become a cyclist or an endurance athlete in general? And what were some of your biggest successes in your your racing adventures and what were some of your biggest learning opportunities?

Julie Young 03:38

Gosh, I just had such a circuitous path to cycling you know I think Colby wouldn’t probably same for you if we didn’t have high school mountain bike league or those those kind of cycling development opportunities and I won’t go too far back and bore you but I’ve always been athletic always been seeking out you know, whether it was literally baseball or swimming and I kind of landed on soccer and alpine ski racing and was on my way to a college, college scholarship for soccer and I tore my ACL as a sophomore and was just devastated because I was so bound and determined to play a sport in college and just mentally finally picked up the pieces and just kind of got a hold of myself and figured out like okay, what can I do like what can I play? What sport can I play in college and kind of get myself ready and so I’m like okay, golf. That’s I can do that with a bad knee and so it kind of just put my head down drove my mom absolutely crazy because I was so determined like at the course you know, sunup to sundown, practicing and was accepted to UCLA tried out for their golf team made the team was on the traveling team went to NCAA, came in academic all American, and then started having some issues with qualifying and was at this Crossroads like, do I want to pursue golf? Do I go to a small liberal college in Florida to do that? Or do I stay at UCLA and pursue my education and I decided, you know what, I don’t love golf. Like, I really value my education. So I stayed at UCLA. And I still needed an outlet. You know, having been an athlete, like, I’m like, I need to do something. So I started running like 10K’s and I bought a bike – That was interesting. We’re starting to ride a bike in LA. And like, I think I got sprint practice across trying to cross the Pacific Coast Highway. Because anyway, but that’s kind of where it just started. I just started riding. And it was just again, to have that outlet, that that movement.

Julie Young 05:55

Then I graduated from UCLA, I moved back to Northern California, got a job in foreign investment, and was riding the bike, just, you know, like commuting into work doing the same thing every day. And there was this human interest story on one of our local news stories on the McKinley brothers. And you probably remember, Scott, and I kept drawing a blank on his brother. But anyway, two brothers that were on the 711 team at the time, and they were going to the Olympics. And I was like, Oh my gosh, there’s bike racing in the US, like, Who knew? Had no idea? Like I remember, the very next day, I ran to the bike shop, talk to the people, like how do I do this? What do I do? And, you know, just kind of thinking about it, like, like, it was their kind of like, negative and just like, Oh, it’s really hard, you have to get a license, like, I don’t care. Like how do I do this, sign me up. And so did that. And then like, I think the very next thing I did was probably run to the bike, or run to the bookshop and bought Greg Coleman’s book, and like, I train myself based on his book, and like, I have that book still. And like all the underlined words, and like verbatim, I trained myself off that book.

Colby Pearce 07:11

That is funny.

Julie Young 07:11

And yeah, and so it just was such a good fit for me. And like within a year, now quickly came, went from a four to a one. And then within that year was identified by the national team, and was invited to like one of their identification camps. And then at the end of that year, was invited to go on kind of one of their national team, like be trips to Japan, it was the year before the world’s in Japan. So race there and did really well. And then that winter, was invited to the actual national team camp, which was in Texas at the time, because Lance was on the team, and he was kind of calling the shots. So we were down in, we were in the hill country of Texas, and I did, we, you know, it was like, a training camp where we train during the week, and then on the weekends, we’d go to like, the local races, and I did well there and was then asked to, you know, go on my first European trip, and that was to Holland, and ended up winning the points jersey at the Monhighkey, and at that time, like, I kind of transformed myself from like, what, initially I was more of a sprinter to a climber. And so, but did well at the Monhighkey and, and then that kind of started my 10 plus year career on the national team and, and at same, you know, subsequently or, or, in same time, was on the proteins like Saturn.

Julie Young 08:52

Yeah, so that’s kind of the circuitous route to cycling. And then, in terms of, you know, successes, I think, for me, I really, I thrived in Europe. And I think, for a lot of people, Europe was just culturally too hard. There’s too many, like factors going on. And I just absolutely loved everything about racing in Europe. I think it’s, you know, it’s super chaotic, but I also feel like the chaos and the little roads for me, like the type of rider I was created opportunity. You know, I wouldn’t say I was a pure anything like I wasn’t a pure climber wasn’t a pure time trialist. I just had work ethic was willing to stay at the front and was willing to try and also had, I think, pretty astute tactical skills. And so for me, I loved Europe. I mean, I just, I remember having days where you kind of just felt so wrung out like you know, end of the stage just sitting on a curb. And because you feel like I mean, you know how it is you just feel like you’re fighting for your life. Over there. Yeah. So it’s just mentally exhausting. But yeah, I just loved everything about that. So I think for me, you know, my, some of my biggest successes came racing in Europe, like winning the GC at the Tour de L’Aude, which at the time was, you know, considered like Tour de France for women Tour de Aquitaine and then just bunches of stage wins in the various stage races we did there like the Monhighkey and BEC. You know, I think, you know, is on six world championship teams proud of that. I do think like, I think about this all the time with with the, like, World Champs, you know, it’s definitely a team sport. And it’s unfortunate that the just the winner is given that medal, because you do realize, like, it really does take the team effort in the road race to get that medal. And definitely was, was excited to be part part of that some of those podium winning teams. Another another, like, really proud result I have is, I had been on the Saturn team, and from the start of that women’s team to ’98 and had decided that, you know, I’d been pigeon holed into kind of a, we had such an incredible team like Clara Hughes and devita met and Jeannie go lay and Karen bliss and it’s slowly been like, pigeon holed into a Domestique. And it really, it took away, like, you know, all my confidence and I didn’t come into the sport to be like, in that position, I came into the sport to try to win. And just mutually agreed it was time to move on. And so I work to get a pro contract with an Italian team, but it had been training down in Southern Cal and, you know, at that time, like you could go into too Redlands as an individual. And so I remember I had, I was working with this coach mirror, and we were down in Alpine training and so made my way over to Redlands and the Oakland stages is you know, it’s a point to point and I was barely able to get a ride to the start because I had no support there at all. And and then I just rode that race and just was road smart and you know, played my cards and ended up in a in a break with two Saturn riders and two Timex riders and, um, you know, just, again, allowed them to kind of focus on each other and, and I attacked on the climb and went solo for the win. And that was, I think, one of my best, like, you know, it’s kind of redemption in some ways. So that was a pretty good success.

Julie Young 12:59

And then I think the other things that I’m proud of that, like, I remained ethical, and throughout my career, you know, I think there’s not much conversation. At least I haven’t heard much about what was happening in the women’s peloton during the era of EPO, but it was happening, you know, and I think, and again, this is just my opinion, the differences like and you hear people talk all the time and describing the men’s peloton, and they talk about an even playing field, you know, basically everyone doing the same thing. And, you know, that wasn’t the case in the women’s field. You know, there were certainly women that did test positive, and but there were women that, that weren’t doing that. And I mean, personally have tons of stories of getting the pressure to do the medicine. And, you know, maintaining that integrity, it never even entered my mind. And so for me as a clean athlete, you know, one win was like 10 wins. But yeah, I just think it’s, it’s interesting. There isn’t much conversation about it. I think it was kind of pushed under the rug. So

Colby Pearce 14:11

yeah, thank you for saying that. Yeah, that’s, that’s important. You know, it’s, well, I wrote down several notes. I didn’t want to interrupt your flow here. But a couple things. Like I want to go back just for a second to say that you read Lemonds book, and, and trained according to that book. That’s so interesting, because I just broke that book out yesterday, while I was doing a fit with a writer and talk to him about how it was basically the first book I read, and there’s still some pretty good advice in that book. I mean, it’s it’s fundamental in some ways. Um, so it’s funny.

Julie Young 14:45

Yeah, that is super funny.

Colby Pearce 14:48

And then you got to race your first race in Japan. How amazing is that? I was lined up to do the tour of Okinawa, maybe four years in a row and like one year I got the flu and another year the national team ran out of money and another year like a hurricane came or something. And never got to race over there. And I finally got to go visit Japan and drop off my daughter. She attended school there last summer. Wow, what an amazing country. Just that must have been super cool experience for you to go race there for the first time. Was it Tour de Okinawa?

Julie Young 15:15

What we did – It was like the series of kind of crits or circuit races in, like their major cities. And we’d so had – I think we’re over there for a couple weeks – so we hit those races, and then they they’d have a stay in the countryside between and I was so amazed. Like, I just didn’t envision this this country that was super impacted. And Gosh, the countryside, so beautiful and such amazing riding. And I do remember like, they really loved their vending machines. And like, literally, I’m not kidding out in the middle of nowhere. There was like this extension cord through this farmer’s field to put this this this vending machine, like on the side of the road. Yes. So crazy, like and they love their iced coffees. And anyway,

Colby Pearce 16:07

And you can get anything in these vending machines, right, like, literally Yeah, yeah. Especially now. Yeah, it’s crazy. But anyway,

Julie Young 16:14

it was a fantastic opportunity. And just a lovely, lovely country.

Colby Pearce 16:21

Cool. Yeah, this is these are some of the gifts you get from the sport, right?

Julie Young 16:25

Totally hundred percent.

Colby Pearce 16:27

See all these amazing cultures and learn stuff. I mean, not always sometimes I would fly to a foreign country and pretty much see the hotel on the inside of a velodrome. There there weeks of my life that went that way. Oh, it was I really in the country. I don’t know. Arguably not but still.

Julie Young 16:43

Yeah. And that felt like a tease. I’m sure.

Colby Pearce 16:45

A little bit. Yeah, a little bit. So that’s cool. That’s great. Yeah. What a cool experience. Yeah, I mean, Saturn was such a women’s powerhouse team. So you’re on that team, from what 93 to 97. Is that about right?

Julie Young 17:01

It was 94, 94, 95, 96 and 97.

Colby Pearce 17:07

Yep. Yep.

Julie Young 17:10

Yeah, such, you know, just good. Like, those people were more our families in some respect than our family, we, you know, you probably felt the same, like you were just with, like, I was with me to met so much, you know, whether it was national team or more, or Saturn, you know, many, many more days and hours with DD than my family.

Colby Pearce 17:32

That’s exactly the way it went. I have some Chekley teammates who I spent more time with and my family during certain years.

Julie Young 17:40

Yeah. Great. Yeah, such good, good memories. Deedee and I were always seemed like we were always stashed away together in Europe and the time, you know, we didn’t have like the fancy US, you know, service course. And, you know, like, I think sometimes like this one time, in Germany, we were stashed away in like a safe house or something is so bizarre, but anyway, just created some really good memories.

Ethical choices in cycling: doping, motivation, and jaded former athletes

Colby Pearce 18:07

Yeah, and then I want to come back to that point you made about ethical choices. And from my own perspective, you know, I look back on that era, too. And I, having heard all the discussions about doping, and about people’s lines on it, it’s um, and having several colleagues and friends who have gone in every possible permutation of that road, or for every possible outcome and made their own choices, I try to select my line of thought and my words very carefully, because I also can say that I walked in my whole career and made the ethical choice, never, never jumped on the sauce train. But I’m also conscious of the fact that, given my circumstances, I in particular wasn’t presented with the opportunity that could have seen my own downfall, that is to say, I’m a firm believer, and I figured this out. A million years ago, in college, when I was taking all my philosophy courses, it’s like, philosophy courses are all about presenting you with some ethical challenge. And they, you know, are you going to kill one person actively to passively save 50, you know, and they put, they give you some elaborate thought experiment with a train and a cat or something like that. And, and you have to sit in class and debate these answers and, and it’s very useful and very instructive, and it brings about for me anyway, because I’m such a philosophical person who brought about all these really emotional responses. And it’s easy for me to feel that way retrospectively about doping. Um, I do have all I’ll say, a sense of there times when I can look upon my some of my colleagues who have made those choices and with a sense of disappointment in a way, but I also feel that I have to constantly keep myself in check because I’m aware of the fact that If I was 2%, better, as a bike racer, or maybe had made slightly different choices in how aggressive I was about my own racing path, I may have been, there may have been a moment in my career, I was sat down at a table, and someone put a contract on the table and said, you’re gonna make an actual salary, like a real salary. But you have to do this, this and this. And I never got to that point. But these some of these other people, well, all these other people that I’m thinking of did get to that point. And it was perceived at the moment, it was painted as the only path forward. Of course, it wasn’t we’ve always everything is a choice when it comes down to it right. I fully believe that being an adult is about taking absolute accountability and responsibility for all of our choices, no matter how boxed in we think we are. But I wasn’t quite good enough realistically, when it really comes down to it to be in that position where someone was going to offer me that choice. I don’t know what how do you feel about that? What do you think about that?

Julie Young 21:06

Well, I guess what I think about it, is that when I look at the Tour de France, and, you know, everyone is expecting these athletes to create, to perform in a sensational way. And these, you know, three weeks, and we want the courses every year to be more demanding, and the finishes to be faster. And, you know, we’re not expecting these guys to doddle. Like, we’re expecting them to race, every race in it to be exciting. And personally, I feel and I know, this has been said that the riders really are pawns. And I do you feel like it’s the organizers, and you know, the sponsors, and everybody that’s expecting these incredible performances, like, I don’t feel like you can humanly do what we expect these riders to do, without some assistance. And so that’s one one thing, I think about it.

Julie Young 22:08

On the other hand, I also think, you know, just personally, like, I feel like I was genetically talented, I know, I had work ethic to back that up. And it was really depressing. You know, like when I was in, so I felt like, Europe helped me raise my game. And I wanted to, you know, I was contending for, for podiums for top 10s you know, always like, one of the best US racers in terms of GC finishes in the stage races. And I felt like if I move to Europe, that would give me that consistency to take my my performance to that next level. And it was like when I moved to Italy, every – like you when you came over to visit so you know, like the situation – and like I was living in this apartment, and nearly every week, the director or the owner, the team would come over and say like, you train too hard, you need medicine and, and you know if the first one I when I started there, like I was the first of the season, always contending for the podium, always in the break. And then I came home to the US to do nationals important, important races for World selection. And when I went back, I was lucky to be competing for 10th or 15th. And you think to yourself, like I just remember in the zero, there were we had a day with two short stages like 70 k in the morning and 70 k in the afternoon. Flat, super windy. And this gal that had been a world champ on the track attack, she went off the front people tried to bridge to her they couldn’t. I finally did bridge to her. But I was so gassed, I couldn’t do anything. And she was just aggressively like trying to take me off her wheel. So I drifted back. She She went on to win that stage, and then the afternoon stage in the same fashion. And you’re thinking to yourself, and this is like I work hard. I’m talented, like what is going on? And you know, later it came out she did test positive, but it’s a bummer. As a clean athlete. You know, it’s like your what’s your hope? Or what’s your, like kind of purpose anymore? So anyway, I would say those are the things I feel about it. I think, though it’s kind of contrasting.

Colby Pearce 24:32

You were saying how the organizers expect the athletes to do these amazing things. And we as fans expect the athletes to race we expect the racers to go out and attack each other and smash it. We don’t want them to just parade along for for two hours if we give him a really long hard stage. Because that’s boring to watch and it’s doesn’t make good TV and we want drama and we want excitement. What I think is interesting about that is I remember having, specifically having a very pointed conversation with one of my Shaklee teammates, Matt Shara, sometime in I don’t know, it’s probably the first year I was racing on Shaklee since probably 96. And he pointed out to me that cyclists, professional cyclists are entertainers. And I had a really hard time with this, I got quite upset when he tried to tell me that what I part of my job was to entertain the public. I didn’t see it that way at all. For me, this was my own one man mission to be the fastest bike racer on the planet. I could give two F’s about what someone thought whether or not what I did was neat. I didn’t see that side of it at all. I hadn’t learned to see an athlete’s performance through the eyes of the spectator. Even though of course, I was a spectator because I had watched the Tour de France on TV I’d watched, you know, Greg LeMond beat Laurent Fignon in the tour in 89, by eight seconds, and I thought it was amazing. And, and I got wrapped into that drama. Um, you know, I knew what john touches music sounded like when I watched the tour coverage. But as we all did, but I I couldn’t put myself in that position. And so I was upset that he thought, in my own head, I was still a long way from any of those level of athletes, I guess. And so I hadn’t conceived of myself as an entertainer.

Colby Pearce 26:19

I think what the problem I have with this philosophically is that when we are this goes into product design, when first of all, we start thinking of athletes as a product or race as a product that can be sold, then we start thinking about how to optimize the product. And then there becomes this balance. Are we going to make something that is the oyster of the creative mind, right, every small company has the origin of this creative design, whether you’re making a shoe or some music, or, you know, a new amazing microphone that works in a different way. I’m obviously looking at the microphone we have right now. And that’s what’s so any product that’s made can be thought of this way, we have this creative impulse this person who’s this creative genius, like remember, Bart Sheldrick used to make those crazy law shoes that I used in 98. That looked like carbon slippers, right? This perfect example, he’s just a, an insanely intelligent and also crazy creative dude who could work with carbon fiber and decided I’m gonna make a cycling shoe in my basement, and he did it. And he his product, the philosophy of his product was I want this, so I’m going to make this for me, and then other people wanted it so he’s able to sell them. That’s a very different process than the way most companies work, especially as they begin to scale. When a company scales, what they do is they have to start making products for an average audience or an average man or woman. And as the saying goes, there is no average man or woman. So when you make a product for an average person, you’re not actually making a product for anyone, what you’re doing is making it effectively a one size fits all solution. Well, in the world of sports, when you start to make a product that fits that, that more is better mentality. Or eventually, when we want sport, arguably, to become a little more X Games and a little less old school boring parade, because that doesn’t play well on TV, especially for what we imagine the average spectator, the average person who sits down American TV watcher, who might expect football which, which is helmets and people smashing into each other over and over again, for a couple hours. Cycling doesn’t work that way. It’s not the way it plays out. So when we start to evaluate the sport based on those standards, then we imagine that the athletes have to do things anything different than what it is. But the fact is, when you know, cycling like you and I do when when most of most of my audience does, or all my audience does, we understand that. All you need is a road and some bike racers. And you’re going to get drama and excitement. Because it’s the race that happens. It’s the passion for racing, that makes an exciting race. Now Yeah, there are different outcomes. I mean, you know, 80 mile flat road race only has so many outcomes in most occasions. But when we add some add a little bit of wind and you know, paavai, and a few hills and some turns, and a couple dogs in the peloton, or maybe a horse and all of a sudden we’ve got a story, no problem, especially if we put an experienced peloton in there with different abilities. That’s what’s cool about cycling. So I see that side of it.

Colby Pearce 29:26

I think that the entertainment side of things, and I’m just sort of thinking out loud here. I think I think the entertainment side of things can drive that to a point. Um, but I also think in respect to your comment about being in a hard position as an athlete who’s clean and going, like you said, to these zero stages and and being in the breakaway with this woman and just having her, you know, rip your legs off. I’ve had that experience as well. I experienced that for the first time in 94 in Belgium. It was one of those moments when you just know how fit you are and how fast you are. And you’re at the front of the race and I was also in a breakaway at this moment, I was actually bridging to a breakaway of I think three or four riders. And a guy came out of the peloton and came to me and took one pole and just ripped me straight off his wheel on a flat road. And look, I know I’m not, you know, Lance, or Miguel Indurain, or whatever, but I know my own engines capabilities, and I just literally stopped pedaling. It was like, seriously, it was just one of those moments where like, How’s this possible? The the delta between me and this other rider is just too high. There’s no explanation other than the guy’s jacked up on goofballs, and I don’t know what else, and you just take it for what it is. Now, I think that can be a very decelerating or minimizing perspective to have for sure. And I experienced that many times. But I had,

Colby Pearce 30:27

I did hear an interesting philosophy from someone, I don’t remember where it was recently. And his take really flipped the coin for me on this. And what he said was, when you know, someone’s doping, you know, that they’re, they’re vulnerable, and you could beat them. And the reason is, because they don’t believe in themselves, like you do, Julie, they don’t believe in their own abilities. So they’re, they’re reaching for something extra, the only way they feel they can win or succeed, is to reach outside themselves and seek something external. In this case, which is contrary to the philosophy and spirit of the sport, to boost up their own level. And the moment they do that, you know, that they’re mentally weak. Now, that was an awesome philosophy, and I really dug that. However, I don’t think that applies to Ebo. Because the delta between a rider who’s clean right on Ebo, when back in the days when it was like cowboys and Indians, I mean, 15 America points, like, you might as well just on engine in their in their bike, right. But I still think philosophically that applies.

Colby Pearce 32:07

Um, from my own perspective, I knew there were guys who were on the sauce that I was racing against, I could see it clearly. Like in that instance, in Belgium. Somehow, I feel, maybe I was just hopelessly naive. But I just felt like I was I drew a little boundary around that part of myself. And I promised myself It didn’t it there were times when this boundary was tested. But I basically promised myself that I would never let other people’s bad decisions, compromise my own flame for the sport or extinguish my joy for the sport. I just made that promise. I don’t even think it was really conscious. It’s not like I sat down and looked in the mirror and said it. I just knew that there was a certain place, I couldn’t go with it. And I think part of that was being on Shaklee and racing with colleagues and teammates, guys like Scott Mercer and Matt Shara, who were really talented athletes, really good bike riders, but they had this jadedness about them because they were looking at other members that peloton and saying, I know, this guy’s on the sauce. I know this guy is using duplicitous methods, and it bought, it really, it started to erode their passion for the sport. And I just, I promised myself I wouldn’t let that happen. It could have been just straight up, maybe? I don’t know. Do you have thoughts on all that?

Julie Young 33:23

Well, I mean, I agree. Like, I think I definitely had these moments where it was discouraging. And it’s tough. Because even though in your mind, you think, gosh, that just doesn’t seem right. You still don’t really give it full credibility, like, Oh, you know, just Buck up get better, you know. So I think there was still that side of me. Like, I never became jaded. Like I still, I still love the sport, I still, you know, I love the sport for all the opportunities it provided to me, you know, and then, you know, one of your questions is, what are, or what were your what were your biggest learning opportunities, and, I mean, I really loved the sport for, like, the opportunity it provided for me to learn about myself. And that’s really what I clung to. Like, for me, the sport was never about beating people, it was always about this opportunity to so like, so vividly learn about myself, like you’re on the rivet, you know, and it’s, it’s like, what I really loved is like, what I was mentally thinking how that transformed how I was physically feeling so I think, you know, I didn’t let the whole and again I didn’t even know for sure if the drug thing was happening. I knew what I was dealing with and I was getting handed pills and tin foil and you know, they were vials of in tackle boxes, you know, but I didn’t know for sure. So you know, there was always that side of me that was like, you know, you kind of think it’s going on but there was not talk about it. So anyway, I think for me my focus did more state on what the sport did for me and why I went, why I came into the sport. And that sense of opportunity for self challenge and growth, and more like almost in the more than mental capacity of growth, then, you know, of course you love the sense of how the physical made you feel. But I really, I love that part about the sport is it just mentally was so empowering.

Colby Pearce 35:25

Really interesting, what you just touched on there about how you said that, for you, the sport was never about beating other people, I identify with that line of thought so strongly, I think that they’re, broadly speaking, in my experience, we could divide all the athletes in into two camps, all the athletes in cycling, and on one side, we have people who are there just to express dominance or superiority or to prove that they’re better than other people. You know, I mean, most obvious example of this is Lance, right? He just all about beating all of his competitors across all levels. And, and not just physically not just crossing the line in front of them, but also bullying them and controlling them and all those things that we’ve read about in the press.

Colby Pearce 36:13

And well, on the other side, we have athletes who are looking internally to push themselves or learn themselves, or I think you said, you have an opportunity for learning about yourself right to test your own boundaries and find out limit. And I was definitely on that side of the sport. In fact, I think this plays into a very interesting psychological perspective on cycling in that when I was a younger rider, I was far better at time trialing than I was at mass start racing. And I think that I’m in the minority in that respect. In fact, I would imagine there are some people listening to this podcast who have probably never thought of it from this side. I think it’s that much of a minority, I couldn’t guess on the percentage of people who are that way. But I was just better at going out and throttling myself on a random Colorado road with a bunch of cows on my own. Then I was at getting in a race and learning to race around a group of people. And because I don’t thrive on making other people suffer, necessarily, that’s not my, that’s not my gig. So I have to approach my mass start racing my very different perspective. And to do that I had to learn to race against other people psychologically, it took a long time to do that. And what I found was interesting was I kind of specialized in time trials at a very young age. And then as I focused on the mass start of aspect of racing, I got my time trial and kind of suffered a little bit got worse. I think there were some other factors that played into it there too. But, and then I had to kind of relearn how to suffer on my own. It was a really interesting evolution. Did you find anything similar? In that respect? Were you a better time trailist? Or did it not matter?

Julie Young 37:53

No, it was horrible. Time trialing. I think I think I have way too much add for time trialing. Like, I mean, I like, it’s funny, because I would think about the time trials I did. And I’d be like, thinking about what I was going to have for dinner, whatever, not not good focus at all, it was something that I definitely really committed to work at and be improved, because like, for me, as a stage racer, you know, became such a, such an important part of the overall. So I definitely committed myself and did improve. But definitely, it was not my natural propensity at all.

Julie Young 38:32

But the one thing I think I love about the mass start racing is like, I would never race as hard, take my game to such a high level without my fellow competitors. And that’s the thing I really appreciate about and still do, like, I love – mass start racing is such an opportunity to learn on so many levels. And it’s really the fellow, your fellow competitors that help you take your game to that next level, and, and learn on so many levels. And so that’s how I saw it more like, again, I didn’t see it as like, I wanted to beat these people. I just it was like this opportunity. Like they pushed you to this point where you were able to learn so much more about yourself. Yes. And that’s really what I appreciated about it.

Colby Pearce 39:20

That I think that’s a really beautiful perspective on looking at mass start racing. And I think I would imagine that many people don’t really consider that perspective, I think superficially, you think about competition, and we think about it in terms of beating the other person and having them push you But in a way, if you’re leading on a climb, you’re thinking about how you’re inflicting damage on other riders. If you’re following on the climb, you’re thinking about how the other person’s or the other riders in the group are suffering or how the person on the front is suffering, which of course, when you break that down, none of those arguments make sense. It’s just a way for you to deal with the effort. Right? But yeah, unless they’re pulling into a real The big headwind. And then one

Colby Pearce 40:04

Last point I want to make on this section is just, I think that it occurred to me as we were talking about being jaded or not being jaded from our experiences as athletes and then progressing into the coaching evolution, or, as Paul said, in the podcast I just released with him, the “guardians at the gate” is how he termed the coach, right, as we are mentors for our younger athletes or not necessarily chronologically younger, but in terms of sporting age younger. And I think that if we were to really recognize that we were, if we, if we did adopt, adopt a jaded mindset, or we did become jaded from our experiences and sport around doping, and we carry that into our coaching, I could see how that would undermine some of the relationships of our athletes, because I know you’ve experienced this too. And I’m gonna paint in a broad brush for a moment just to use a parallel example. I have had many experiences in my life, where I’ve worked with mechanics, who have been bike racers who didn’t make it. And then they became mechanics. And then they become, then they’re a little bit jaded. And there’s this sort of, again, I’m painting a broad brush here, I’m not saying all mechanics are dicks. But I’ve definitely experienced this archetype who will say, the mechanic who didn’t make it as a pro, and then he’s working on bikes, and he’s a little upset that you’re you made it as a pro. And then there are these underhanded sort of comments. Occasionally, there’s passive aggressive behavior and distribution of equipment or similar things. I’ve seen this theme many times, and, again, worked with some amazing mechanics and grateful for the mechanical support I’ve received in my career not trying to bash mechanics, but it’s a thing that happens. And I could imagine, they’re also coaches out there who are similarly minded in the sense that they may have felt that their opportunity to succeed in sport was robbed by doping or, or taken away by cheaters. And I think that on the one hand, our job as coaches is to paint a realistic picture. And to we don’t need to sugarcoat everything about our athletes, like the reality is their athletes, as long as their sport, there are people who will cheat their athletes who will look for shortcuts, it’s just, unfortunately, human nature. So in a sense, when you’re just like when you’re raising your kid, and you have to tell them like, yeah, there’s going to be a thunderstorm this afternoon, you should take your rain jacket, you’re trying to arm your athletes with the tools they need to deal with the adversity of their sport. And in that sense, we want to make them aware of the fact that they’re going to have to deal with dopers and cheaters. And, but hopefully, there, we are equipping them with the tools to deal with that. And if our jadedness came out, what I’m saying is, we might, we might be at risk of potentially extinguishing their joy for the sport. Do you have thoughts on that?

Julie Young 43:05

Personally speaking, I think this, this is part of my history. But it’s funny, I, I, it doesn’t come into play at all, in my, like, my mindset at all. Really? I mean, you know, I do think about, perhaps, with some of the younger athletes that I’m training and coaching, you know, and they’re doing some of the, like, the US World Cup type with, they’re not World Cup, but the US National type races, you know, you kind of wonder, in the back of your mind, you’re like, it’s more just like, gosh, I hope, hope everyone’s clean. You know, I hope there’s a level playing field, but it doesn’t, it’s, again, it kind of goes back to like, yeah, this was a, this was a part of the history. But for me, again, I left the sport with so much love of the sport in such a positive experience. And again, it was just this opportunity to, you know, ride and race with abandon and learn about self and, and that’s really what is more guiding in my, you know, as I as I coach, yeah, that’s really more of the guiding principle. Yeah.

Colby Pearce 44:18

Well, I would argue that that’s why you’re still have passion for the sport, you’re still coaching because you follow that principle yourself. Right?

Julie Young 44:27

Yeah, I just think it does. It’s again, it’s, for me, it was never like we said, it wasn’t about the competition. It’s just this opportunity to learn on so many levels. And I think that’s, you know, I have a lot of former teammates that don’t ride their bikes anymore at all that just have like this really, you know, kind of just so burnt and bitter, and just was approached differently.

Colby Pearce 44:51

You might say, a dour disposition towards the history, their history in the sport,

Julie Young 44:57

perhaps Yeah, well, I think just maybe how they are They approached racing. And that was also tied in results. And, you know, maybe to a fault I was. I wasn’t ambitious enough in terms of results. But I really felt like when I raced, like if I left it all out there, I mean, I race smart, but I really, sincerely, you know, after the race evaluated, like, did I mentally and physically leave it all out there, I was so happy like I was so content, whatever the results were. And I think that allowed me to have a really healthy relationship and like, love the sport and continue loving the sport, versus having it all just completely based on the outcomes.

Colby Pearce 45:43

Yep, your actual placing that’s so interesting, I had a real powerful teaching moment, there was a Canadian track coach, his name was Eric. I don’t recall his last name. And I would run into him at various World Cups and kind of ended up striking up a relationship with him. And he would offer me little, little nuggets of advice now. And again, even though it was there to coach the Canadians. He just felt that I needed to hear some things. And one of the comments he made to me, which at the time was quite perplexing, which resonates now quite powerfully with what you just said about how almost to a fault, you could be engaged in racing, and happy, you could be satisfied with the outcome, regardless of the actual placing if you felt like you’ve done your best performance. And I definitely had that perspective at times during races. And at one point, I don’t remember if it was, maybe it was after a points race qualifier or something he came to me. He said, Yeah, you’re an interesting racer, because you actually don’t want to win, I can tell you don’t care what place you get. And I was like, What do you mean? And that’s basically what he was saying. He was saying that he could observe in my racing performance, that I wasn’t there to crush people, I wasn’t there, I was not there to earn an external place necessarily, I was there to, to test myself and to learn about myself and to express my, you know, whatever, show myself what I could do, internally. And I think what he was trying to do was call me out and say that there was a balance, that, ultimately, to be a competitive athlete, you have to balance the desire to test the internal with the desire to execute and, and cross the line in a certain place, the best possible place you can on that day, you have to hold yourself accountable. And that was the lesson that took me a long time to learn.

Colby Pearce 47:27

And I think that’s what I’m trying to say is I I definitely identify with with your sentiment of almost to a fault at times, I kind of didn’t care what place I got, I distinctly remember making what I would consider to be that was like the first time I made the break in a one-two race in a local crit. And I, and that was my objective for the entire race. It was like that was my chess match. I’m gonna make the break today. And for whatever reason, that was the way I had framed that crit in my little, you know, 21 year old mind, and I did it, I made the break, it was six riders. And then I played this like to look at in retrospect, it’s just so vintage me. But I, in my head, it was like, I’d already accomplished my goal for the race. And not only to not not only that, I had convinced myself that I had zero chance of winning the race or being in the top three, because all the other riders in the breakaway were better sprinters than me. So I had performed this, you know, logic table in my head and realized that I was going to get fifth or six no matter what. So in the last half lap of the race, I just let the break, go and cross the line in sixth. Not even contesting the finish. But being satisfied that I had made the break and was crossing the line. You know, making my $14 or whatever I was going to get for six plays ahead of the peloton. And I consider that a win. Until when I crossed the line. I looked in the crowd and I saw people, a couple of people who are watching the race and knew me and looked at me with this puzzled look, they weren’t celebrating the fact that I had made the break, which to me was this amazing victory, you know, it’s the first time ever made the breakaway and the one to race. They were looking at me like, “What are you doing moron? Sprint!” You know, and, and I had this instantaneous understanding how much i’d screwed up. It’s like, Oh, right. Bike racing isn’t only about solving the puzzle, you know, and getting the magic piece, it’s about the place you cross the line and or at least trying to cross the line in a better place. And that’s how you’re going to learn to push yourself. So anyway.

Julie Young 49:34

Yeah, and I think, you know, it wasn’t so much that I was totally disregarding results, but I felt like, you know, if I focused on just racing, again, to the absolute best of my ability within the race, and you know, again, racing smart, so not being tactically astute and clever, and I just felt like really focusing on that. That the results. They really did come. And versus entirely being just totally stressed out, and not enjoying the moment or, you know, not that you necessarily enjoy those races because they’re so darn hard. But I just felt like if I focused on racing that way, most often the outcomes and the results are positive.

Colby Pearce 50:23

Yeah, that’s type two fun, right? Races, they’re not really fun while you’re doing them. It’s afterwards when you go, Man, that was so epic, then I bridge across that crosswind and follow myself on this climb for half an hour. And somehow I did it. And then then I got dropped. And then I cut back on and then I won, or whatever you know…

Julie Young 50:42

All about the stories.

Colby Pearce 50:43

It’s all about the stories. Yeah, you’ve read Tim Krabbs book, The Rider, I take it?

Julie Young 50:50

I have not.

Colby Pearce 50:51

It’s kind of these stories. That’s what it’s about. It’s for someone who doesn’t really understand the core elements of the battles that take place on this on the course. It’s a really fascinating look at how that all develops. It’s basically the story of a long road race. But it’s told in a very artful way. It’s a I think the guy’s Dutch author. Yeah, classic read. Well, we’ll drop a show notes, thing or bobber in our high tech list of our high tech grocery list here.

Colby Pearce 51:23

So we have a few minutes left, if you don’t mind, I’d like to talk a bit about how you coach your athletes. What kind of metrics do you do you track when you’re coaching an athlete? Um, well, first of all, let’s define the playing field and give a bit of context. Are you only coaching cyclists? Are you also coaching athletes in other sports? And if so, then what do we use are using HRV? Are you using Moxie? I know you’ve run a lab. So you’re doing lab tests? Are you doing lactate? Are you doing full expired inspired gas? Vo two? Do you use software like inside to contrast against your lab tests? How you feel about that is a big question. I’m gonna roll it big question. Big question. So many, let’s put all the devices in the pile to use Yeah, tr x’s and I’ll do a kettlebell CrossFit. Go, go.

Using the data, but not worshipping it

Julie Young 52:11

Go! So I do coach other endurance athletes. So after cycling, I forayed into trail running and XTERRA and cross country ski racing. So just kind of have an understanding of those sports. And so if you do work with all endurance athletes, and, you know, I think it’s a luxury in some ways for for cyclists to have the use of power. You know, I, when I work with runners, it’s it’s tricky, you know, I’m working with this gal who’s going to do this hundred k raise. So she was asking, Well, can I go off heart rate per pace? And, you know, I know, that’s just there’s too many factors that, that affect heart rate. So, I think for me, you know, I think you’d, you’d asked about like, coaching philosophy, and it’s not just about the data, it’s, it’s really like, for me, the most important thing in the in the coaching, like philosophy, and then understanding how to use use all the devices is understanding the athlete, and just mentally and physically how they tick strengths and weaknesses. The demands of there are events, I use, like, I really use the data to help inform my decision making, but I don’t like, I don’t use the data to dictate my development of the training plan. So if, if that makes sense. So like, when I’m making a training plan, it’s based on that athlete and all those things I mentioned. And it’s not about hitting a certain TSS, or critical training load score, it’s but But often, in most cases, what happens is those line up. And so again, it’s kind of that that backmarker to basically, you know, confirm the decision making, yeah, or again, to inform the decision making. I do use, you know, I use training peaks and in do again, use those those scores to help, you know, make sure like things are moving on track.

Julie Young 54:19

In the lab, I am still a fan of lactate testing, I think, you know, I feel like we’re in this era of data worship. And I think, you know, again, power is it’s fantastic. It’s such a great training tool, but I feel like people have lost perspective on it. And you know, I think sometimes I see like these these software programs that promise like 2% raise in your power your FTP every two weeks. And you know, I think it’s, it’s, it’s deceptive, and I feel like people have to understand like, you know, and I think people do understand this. It’s not it’s obvious, like your powers Not going to infinitely increase, but it’s what I like about the lactate test is it helps understand what’s going on under the hood. And, you know, like, where I think that lactate line is rich with information, and, you know, dissecting that, and then helping direct the training plan off that and find those kind of weak links. And, and I know like lactates not perfect, either we don’t understand how we get to that end point, we don’t understand like, you know, the combustion of the lactate, and, you know, the production and, but it gives us a better idea. And I think helping athletes understand that, you know, you’re, you may not continually increase that that power, but you’re getting more efficient at that power. And so, for me, it’s just really empowering the athlete with, like, understanding, and I think that’s so important for them, then to really hit their training with more purpose. And, and again, I think that’s really the differentiator, in terms of the effectiveness of the training plan is the purpose with which the athlete gets the training. So the more I can help continually, and it’s not like a one time thing, it’s continually like, educating like, you know, why they’re doing certain workouts and helping them connect the dots to why they are and visualizing themselves in certain aspects, or certain sections of races. To me, like, that’s the best use of kind of all the pieces like it, as opposed to just focusing on hitting certain numbers in a workout. Like, I feel like that really gypped the athlete of, of the richness of a workout, like, I really think they need to be mentally engaged in that workout and be visualizing, like, why they’re doing that workout and how it how it directly relates to their goals. So I guess, you know, I just, I just think there’s just, I don’t know, I like I said, I feel like there’s this this data worship right now. And I don’t, I don’t feel I feel like it marginalizes really what it takes to put together a good performance if, if we’re just focused on hitting a number in our workout.

Colby Pearce 57:20

I agree. I mean, going back to your comments about why you enjoy the sport, and what your passion was, when you were racing professionally, it was to explore your own limits, it was to have a deeper understanding of self. And that’s looking internally into your own. Julie tech ometer. Right. What’s your limit? How, how hot can you run the engine in any given moment of a race? And what limit Can you find and that requires a deep intuition and understanding of how your own body works under load. And we had power meters, you know, back in the day, I mean, 95 is in power kind of came on at 98, 99, 2000s. For sure, you know, most competitive riders have power meters in some form. And and so we started to understand those metrics. But I think we still, at that point, I would say most riders still understood that what you were trying to do was put a an object of measurement on to the subjective, but the subjective is really the end goal. It’s a deeper understanding of self. Your own internal rate of exertion was what we were trying to model. And it was a model and all mathematical models to paraphrase Coggan, directly, all mathematical models are invalid. The question is, what is their domain of validity? How big is it? When is it useful? When is it not useful? Understand the model. Same thing with a performance management chart, you know, that just maps out your load for the entire season. It has all these numbers, we look at just as you were talking about chronic training, load, acute training, load, train stress balance. And I agree exactly with what you said about using the numbers to help inform decisions, but not to dictate decisions. It’s very, very rare that I would ever look at a number and we’ll probably never I would look at a number and say we need to change the program based on this number alone. I would speak to the athlete. Consider the context, because numbers are just numbers. And without, without meaning and context. They don’t have true they don’t give us a full picture of information.

Colby Pearce 59:30

I mean, I could send a rider out to do a 20 minute climb. And they could do it at x power. We’ll take the generically used 300 watts and they climb this climate 300 watts and they upload the file and I can look at their power and I can look at their heart rate and I can have a sense historically of what that means relative to the other athletes other performances. Now if it’s the best ever 20 minute power they’ve done okay, then that tells us something. If it’s a very Average or unremarkable 20 minute power, that also tells us something. But it doesn’t tell me that much unless I read the athletes comments, which requires, of course, the athlete to make the comments, which requires you to have a good communication relationship. But if the athlete says to me, I felt like there was no chain on my bike when I made this 20 minute effort. And it was in the 97th percentile, that’s obviously a much different data point than if they say, holy crap, who tied a dead bear to my bike. I was literally felt like I was getting a root canal the entire way of this climb, but I managed to do it. That tells me several important things. One is they’re carrying some type of fatigue, or their relative perceived exertion was much higher on that day, for some reason, we’ve got to sort out what that was, whether it was that they were, you know, slept poorly, or dehydrated or glycogen depleted or any number of other things, or whether it was a matter of their own perceived expectations, and the numbers falling short of that. And that’s the trap we fall into. When we give a rider the shortcut and say today, I want you to ride at 310 watts for this 20 minutes. Don’t think about how you how you feel, don’t put effort into your own internal sensations. Don’t try to Intuit that instead, just turn all that off, check out from the body and just follow this, follow this line, jump over this line or go into this Limbo bar, however you want to phrase it, right, like a high jump would be a better example. It’s like just as long as you clear this bar, you can go on about your day and go to your job and put your kids to bed and do all the things and not worry about whether or not you’ve air quotes had a successful workout. But like any complex task, it requires a little more discernment, right, it requires a little deeper thought. And the best example, the textbook example I have for this problem of why this doesn’t work is I’m gonna have to get creed on the podcast, again, the OG of podcasting, the original gangsta Mike described going to you 23 World Championships some year ago, so many years ago when he was under 23. And he had a power target in mind for this time trial. And he started the time trial out and was on his target on his target on his target. And then the second half of the race, he was actually holding back a bit because he was expecting to blow up. And he crossed the line and realized that he had significantly under paced his time trial. And whether or not it was his estimation of what his average power for that day should be. Or as coaches, I don’t recall, maybe they probably agreed on it together would be my guest. But he crossed the line. And like I mean, it was an agonizing race, because I think he finished ninth or 10th. So clearly, he left power on the table left power on the course left speed and time out there. And who knows what he would have been capable of, if he had just ignored these numbers. And usually, it’s the other way around. Usually, we set the bar and we’re just barely trying to achieve it. And there can be times when power is a very powerful motivational within that sense, especially when you’re suffering and you’ve got to get the work done days of hard work, you know, we’re talking like a five by eight or something at maximal pace. The last, the fourth and fifth efforts, if we if we’re sure that that’s the work you need to be doing for the day, and we want to dig deep, troque could be a great line to use as a motivator. But that’s different than plugging, unplugging completely and forgetting about what your body’s doing and disconnecting from the self in order to achieve an external goal. Because that the fact is those external goals. There are lots of confounding variables in that equation, even in the world of precision power meters.

Julie Young 1:03:46

I think power is just such an incredible tool. And I think it’s awesome, like so absolute. And I think it’s a great target. But, you know, if at the end of the day, we’re thinking about preparing athletes for events, I think you have to think about what what are all the ingredients that are going to prepare that athlete for the event. And, you know, it’s far more than just hitting a number on a power meter. And like the one thing I just I get frustrated with is I think we so under estimate and continue to it seems like we continue to disregard the importance and I know this is not that’s that that’s strong, we don’t necessarily disregard but the importance of the mental conditioning. And I feel like some of these, these coaches that you know, they’ve had these awesome, like textbook training plans and like, you know, to, to achieve these certain physiologic and metabolic like kind of ideals. And I just like I look at these training plans, and I’m thinking to myself, my gosh, no, I couldn’t have possibly done that. Even training for World Championships. I think they’re so demanding. And I think like you have to understand like what is the emotional tolerance of the athlete and like always viously the physical durability of that athlete, but also like us training for all the aspects of performance like so, you know, obviously nutrition, hydration, but the mental conditioning.

Julie Young 1:05:12

And so like if I’m just if I’m not doing a workout, and all I’m doing is focusing on staring at my device and achieving a number and kind of wrestling my bike to achieve that number, like I’m not, I’m not going away with any tools to take into the race, like, I want to be thinking about actions, like I want to be, you know, mentally focusing my mind on something other than the discomfort, something like the fluidity the breathing my posture, things like when I’m in a race, and I’m in that same situation of discomfort, like I’m gonna have things to lean on. Like, I mean, I know. So I think about times where like, I’ve been in a race and I, I like it’s worth climbing. And I think to myself, no big deal. This is just like intervals on Wednesday, you know, things like that, like, I think that’s the value of training is like providing that that mental and physical confidence for the rider but giving them those mental and physical tools to take into the event. You know, it’s not just about like that, that training session and just simply hitting a number. So I guess that’s where I get a little frustrated with, with the use of power,

Colby Pearce 1:06:21

you particular you have a road race, it’s like we can arm our athletes with all these intervals and these power durations and you know, w prime or FRC, and we can increase all their metrics. But every road race is just like, it’s just chaos waiting to happen. It’s like a whiteboard, and you go into it with this rough plan, you know, oh, we expect that there’s going to be a crosswind in this valley. And, you know, there’s a 60% chance of rain today and 12% chance to hail and cloudy with a chance of, you know, dark and stormy, whatever. And then you get in the race and other teams are doing unexpected tactical maneuvers or blunders. And then you’ve got three flat tires, and the wind is twice as bad as it was, and you drop back to get bottles at the perfect wrong moment. And the field is shattering. And all these things happen in the real world. This is what I love about bike racing. I like to tell my athletes like sometimes they’ll come to me and they’ll say, let’s make a detailed plan for this road race. And I’m going, Okay, we can do that. But just recognize the more detail on time and effort we put into this plan, the less likely it is to come out this way. Honestly, every bike race is at least 50% made up on the spot. You know, it literally is it’s like well, that happened. And this happened and I just went for it. And then it worked out. So you we have to arm our athletes with this sort of robust ability to blend left brain and right brain. Blend, the yin and the yang or the masculine feminine energies, the analytical tactical, doing checklist energy with the man I just knew it was the right moment got hit by a bolt of lightning and attacked made no sense whatsoever. And how many bike races have we seen that have worked out because of that? That bolt of lightning moment, I mean, yeah, they happen all the time. But there are a lot of races that are won that way. Not all of them, certainly, some of them are calculated, you can win a bike race in any number of ways. But I would argue that anyone who gets the line in the league group or gets the line first used a blend of conscious tactics and intuition. So crafting intuition that’s a that’s a big one for us as coaches, right?

Crafting intuition

Julie Young 1:08:39

Yeah, I’m kind of interested if you think like, you can craft intuition, and I feel like, I don’t know, like, I’m sure you had it. But I wonder if you can craft that. But I think like for me a big part of performances, you know, just having that calm and that composure in that kind of the, the moment of chaos. And I think that’s a big part of like great champions, they just maintain this calm and this composure. And again, I think that’s like, you know, kind of comes with, like training. And that’s, that’s another aspect of training is now kind of gaining your confidence that you can pedal through it and you can be okay. And it’s just, it’s just, there’s so many so many aspects to like in the heat of the moment. You know, being able to perform and it’s like fitness is just just the starting point.

Colby Pearce 1:09:38

Yeah. Yeah, so agreed. I would argue that you absolutely can craft performance in your riders and the path to that might be subtle, it might be Securitas to use your your word from earlier, your beautiful adjective and I would also submit that you have been called crafting your own intuition in your own career the whole time. I think that’s what I think it’s a powerful part of what drawing inwards and looking into yourself and testing your own limits is about, especially in the context of a tactical mind. Because, okay, we can have athletes who are internally focused, and they want to test their own limits. And you have different outcomes. On one extreme, we have an athlete who, who wants to explore their own limits or learn about themselves, but with disregard for tactical outcome. And these are the riders who end up on the front of the group chasing down random breakaways at, you know, 48 k an hour for 20-30 minutes at a time, with no real regard to why they’re doing it. Right, we’ve seen this many times, or riders who get in a breakaway, and they pull with a completely disproportionate amount of, of effort relative to the rest of the breakaway. And it disrupts the rhythm of the race. And ultimately, you know, and then they get to the line and they get smashed. And they’re, maybe the break makes the line because this person very themselves, but they get last by long ways. And in their mind, what they were trying to prove is that they were the strongest rider, really, they were confused. They thought they were in a running race. And I said, That’s not the way cycling works. Cycling is a chess match on wheels, it’s all about holding your cards to your chest and playing them at the right moment. So when you Julie, specifically when you were testing yourself and learning your own internal limits, but doing it with a tactically astute mind and trying to play your cards at the right moment, I would argue that is that is really the the crafting of or the balance of intuition and the thinking mind the tactical mind.

Julie Young 1:11:44

But sometimes, I wonder, like, I wonder though, like, I think intuition is just that little voice, you know, like I with my athletes, I’m always like, going into a race like okay, you know, when you’re sitting in and take one gear lighter and position and be thinking the the as the race evolves, like where you want to make your move, but I think like, for me, like when radios came on the scene, it took something away from from me, because I’m kind of like, you know, the little voice comes to me, but then I’m like, Oh, do I do it? Or does the director say I don’t? You know, to me, it’s, I don’t know, if everybody has the little voice? That’s what I wonder about. And that’s when I wonder, can you can you coach the little voice? Because to me, the little voice was the make or break?

Colby Pearce 1:12:29

Yeah. Yeah, I would argue you can. And that’s one of the directives of, of our to do list as coaches is to help foster and create that inner voice for riders to give them that confidence to listen to their instinct. I mean, I had many moments of my own racing career where I days where I got it absolutely right. And days where it was disastrously wrong. I mean, there were road races where I sat 20th wheel and watched attacks happen for 45 minutes, didn’t follow a single one, and then stood up at minute 48:26 fall one attack, and that was the break. And I just knew it wasn’t a – and we can have lots of Claire’s will say we can have Claire audience clairsentience. Right? We can have lots of new ways of knowing people, I believe that everyone’s got their channel to tap into their own intuition in different ways. And so if you actually literally hear a voice in your head, this is Julie go now. Maybe that’s the way it presents itself to you. Maybe you see something, maybe it’s just a feeling.

Colby Pearce 1:13:35

For me, I have, I’ve got moments of all three, and then there moments where it goes wrong where my intuition is off, and I’m following the first 48 minutes of attacks and going nowhere. And then at minute 46:26, or whatever the attack goes. And that’s the last I’m totally exhausted by that. And I missed the move. So these are these are moments refining and crafting your own intuition. And I would, I would definitely submit that we we help to foster that in our writers with our own racing stories, our own history, our own, you know, battle stories about how we did it, right how we did it wrong, that helps them tune into their own, oh, what did I get wrong? How did they make their own comparison and their own stories…

Colby Pearce 1:14:19

But also, I think it’s just about being tapped in. It’s about being grounded and centered, when you’re, and you just spoke to this when your writer is solidly in themselves when they are grounded. And I mean, metaphorically, energetically, sometimes literally, I mean, so many tough talks about how during grant tours, he would go for a walk in the forest barefoot before each stage. This is the kind of stuff I’m doing on a regular basis now only without grand tour part. But I feel that when I’m meditative in my own life, and I have a meditation practice, and that can take various different forms. That helps me tune into my own intuition, and I would argue, a collective consciousness. And what is a peloton? It’s a, it’s a bee’s nest. It’s and that bee’s nest as a member of that peloton, if you’re in a selective group of 24 riders, that’s halfway through a road race. You’re 120 fourth of the psychology of that peloton at least. So if one rider attacks and you respond to that attack, the people who are racing are paying attention are watching and they are reacting to that, right? They’re like, Oh, one rider attacked. What are we going to do another? She followed him, she followed her. Oh, okay, now the race is heating up? What’s going to happen? are three more gonna go? Or are we going to let them roll off the front? What is everybody else doing? So we’re constantly interacting in that mindset of the group. And that intuition is a powerful part of the outcome of races a very powerful part. When you get in track races the peloton they’re smaller. So now you’re one 12th of the psychology of this group collective consciousness. When you’re in a peloton of 150 riders, you’ve got much less of an impact. However, there is an impact. if everyone’s riding piano at the start of a long race after four stages of racing, and you’re the one who draws the first sword. Sometimes that can really influence how things develop from there. Or you choose not to draw your sword. So yeah, just a. Just a bit on that I now that we’re talking about this, I think this is probably a topic worth exploring.

Julie Young 1:16:32

Well, I think the tactical part is just the most exciting part about bike racing. Again, like the fitness gives you kind of that ability to be a player. But it’s, it’s the that’s the playing that makes it fun.

Colby Pearce 1:16:44

Yes. Yes. Infinite game. Yep.

Colby Pearce 1:16:50

Julie, um, I want to say thank you for taking the time to jump on the call today. I know we had some scheduling challenges, and I really appreciate you taking time out of your day.

Julie Young 1:17:00

Well, thank you so much, I just so it’s so enjoyed it Colby really appreciate you thinking about me and inviting me to be a part of this.

Colby Pearce 1:17:11

We’ve reached the end of another episode of cycling in alignment. I hope you found today’s conversation with Julie illuminating. I really enjoyed speaking with her and appreciated her perspective on coaching, and insights on data worship.

Motivation mentalities

Colby Pearce 1:17:31

I was reflecting on a conversation about our different perspectives on motivation in the sport. In particular part where I described that I’m a little bit better racing on a random road with cows than I am racing against other people, or at least I was a young rider. And Julie admitted that she is more on the other side of things, although even in a master race, her objective isn’t to crush other riders, it’s to explore her own limits and learn about herself learn about what she can do in the presence of other riders. I think that’s a really beautiful way to say that sport isn’t about smashing other athletes. It’s not about beating other people and making them feel less than it’s about finding out what you can do. I thought that was a potent and powerful distinction.

Colby Pearce 1:18:23

The downside of that mentality or the mentality that I had, which perhaps was even a bit more analytical, especially as a young athlete, is that you can be not focused enough on the tangible results of racing. If you just want to go ride your bike in the forest by yourself, and you can find your own limit that way, you can decide how hard you want to ride a giant mountain pass on your own, you don’t need a number, or a sponsor or race wheels to do that. You can do that at any point.

Colby Pearce 1:18:54

But when someone is paying you to ride your bike, when you have mechanics, and so on yours and directors and team managers and all the staff that goes into a professional cycling team, in slip streams case, about 100 employees, who are all ultimately supporting the riders in the team. And they’re there, really so that you can get results. If you don’t deliver on the day, then there’s a level of disappointment. That’s what professional bike racers are there to do ultimately, is win races or you’re there to be part of the team and perform your job for the day, whether that’s getting bottles of bringing rain jackets or chasing down breakaways. That’s your job. That’s your finish line. And there were times when I was a long way from learning that lesson and having that own personal accountability.

Colby Pearce 1:19:47

But just like any spectrum, you can go too far in either direction. And I think Julie and I have both witnessed plenty of riderd who have perhaps gone too far down the results road and when your happiness your sense of self becomes too involved or too wrapped around the finish line or the results page of a website, then you can lose what’s valuable about the sport, you can lose the essence of competition, because ultimately, even paid competition is still simply a game. And I have one clear example of that in my own career. I just want to share briefly.

Colby Pearce 1:20:27

I raced local criterium here just a few blocks in my house probably half a dozen times in my racing will say career, more like adventure. And on one of these occasions – This is of course the to to be quite well it was has a small hills, very tactical had a little alley that ran down the backside of the course and several asteroids – And on one occasion, I was in a breakaway with one of my own teammates and another rider and no matter what we did, we could not get rid of this guy. And maybe if the course was a little different, and we were able to attack him back to back more often we could possibly do something. But the way the course played out in this case with the technical aspects that was just not enough space and time for us to hit him within a frequency to wear him down to where we could actually get away. And he was the quickest finisher of the three of us. And I sort of could see this happening about halfway through the race, but there was nothing to be done. We were so far ahead of the peloton that stalling wouldn’t really matter, there was no cat and mouse to play. There was really nothing we could do. And I could see this plot happening in the future. We tried everything we could think of to get rid of this guy. And then we came down to the finish and he just smoked us. And I distinctly remember crossing a line with this just profound sense of disappointment. In fact, I was so upset about it, that I dropped an expletive as I crossed the line. And if I recall correctly, my step mom was actually standing on that finish line. And immediately after I crossed the line, I realized that she probably heard me. And that was a not very proud moment.

Colby Pearce 1:22:16