If you’ve always thought the only way to effectively train for an ultra-endurance cycling event was to commit huge hours to riding, lifting, stretching, and sleeping—and doing little else—you are forgiven. That might have been routine in the past, but it isn’t the only way to prepare for a long-distance cycling event.

The reality is that you can effectively prepare physically and mentally for the rigors of events lasting anywhere from eight hours to weeks on end, even if you only have six hours per week to train. This mark—around 6 hours—became the definition of the “time-crunched athlete” when Coach Chris Carmichael published his now famous book.

It takes creativity and consistency, but with a few modifications to a typical endurance training regimen, you can graduate to the ultra-endurance world.

Foundation building

As with any good training plan, having a solid understanding of your limitations allows you to efficiently choose which areas to focus on in your training. This is particularly important for athletes with limited time.

Ideally, you’d start by completing a physiological test, which helps you (and your coach, if you work with one) pinpoint how you can make the biggest gains in training.

Likewise, things like a gap analysis allow you to refine the most critical training areas to focus on with your precious time.

For Ryan Kohler, lead physiologist and coach at Rocky Mountain Devo, strength training is the other critical component for time-crunched cyclists looking to step into this world. For the first several months of training, he would recommend upwards of a third of your hours be spent in the gym dedicated to strength, mobility, and flexibility.

“We’re building a foundation,” Kohler emphasizes. “You can’t go and replicate an event like [the 200-mile gravel race] Unbound in your training—that 12, 14, 16-hour effort. At those lengths, you will be tired. You will be beat up. Placing a higher priority on strength training—even more than cycling—in the first few blocks is going to pay off in the long run.”

RELATED: Fast Talk Labs Strength Training Series

Finally, as you work to establish a plan, don’t discount information gathering. Watch race footage, speak with others who have previously participated in the event (or something similar), and study the course online. All of these tasks will help you set expectations for what you are undertaking—both in terms of preparation and the experience on race-day—and, therefore, help to create a list of things to focus on.

Creating training stress

Whether you have 25 hours per week to train, or just five, the same principles apply: In order to see fitness gains, you need to create training stress, and then allow your body to recover and rebuild stronger.

Many athletes have a natural tendency to ride harder if they have limited time. In many ways, it seems logical when you consider the above formula (stress yields adaptation). But not all stress is created equal. While base training produces physical stress that slowly accumulates to improve fitness, high-intensity intervals cause biochemical stress that can be damaging—it quickly accumulates if intensity becomes a part of every ride.

“I like to tell my athletes: If the instructions recommend cooking a turkey for four hours at 250 degrees, you won’t get the same result if you cook it for two hours at 500 degrees,” says Fast Talk Labs co-founder Trevor Connor. “The bird, just like the athlete, will get burnt. High-intensity training doesn’t compensate for a lack of base, nor can it serve as a substitute.”

Eventually you’ll hit a ceiling by just doing base miles, particularly if you are only getting six hours of training per week. That’s when you will need to lift or add a bit of intensity. You’ll also want to modify the mixture of endurance miles, intensity, and how the two components come together in succession.

That’s when getting creative with base training is critical to producing long-lasting fitness gains, as well as preventing injury or overtraining.

“At that point, it’s about how we dose you as an athlete to maximize progression while keeping within that volume cap—the bandwidth you have to train each week,” Kohler says.

Creating “stress blocks” is among the most effective methods for base training with limited time. You can do this by scheduling consecutive hard training days. For example, plan an interval session on Friday, a hard group ride on Saturday, and a long easy ride on Sunday. This overload should be followed by ample rest and recovery—the body will have a lot of damage to repair.

Intervals have their place

As we’ve just alluded to, training for ultra-endurance events does not consist solely of long, slow hours in the saddle. According to veteran ultra-endurance racer and coach Jose Bermudez, interval training is an important part of the equation.

Bermudez has completed RAAM, Tour Divide, and TransAm, as well as the 350- and 1000-mile Iditarod events in winter. And he coaches several other ultra-athletes. According to Bermudez, the major difference between training for standard distance events and ultra events is that you want to train to operate at a much lower percentage of your functional threshold power (FTP). If you can make improvements in your FTP, then operating at 60% of it is going to get you going faster, more efficiently.

“I’m interested in raising people’s power threshold, I’m looking at cumulative training load—all the metrics are the same, but the work that we do in ultra-cycling training is very different,” he says. “Not all your rides are long. It used to be the case that people train for things like Race Across America just by riding their bike for hundreds of miles every week. Smart people don’t do that anymore. It’s not efficient, it’s not a good use of time, and it doesn’t actually make you any faster.”

Instead, Bermudez believes it’s better to incorporate things like threshold intervals into your plan. Not only does he believe that this staple of endurance training will lead to beneficial physiological adaptations, it also helps people understand how it feels to suffer.

“There’s a lot of suffering in these races,” he says. “Suffering comes in lots of different varieties, and it’s good to practice lots of different types of it.”

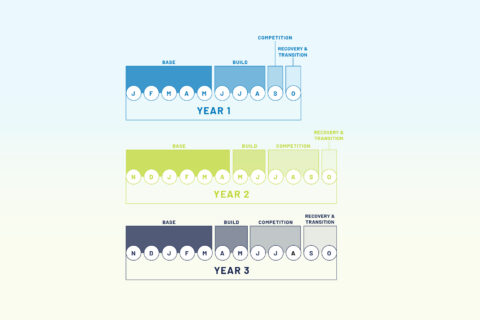

In terms of how much volume you need, Bermudez hesitates to put a number on it. It all comes down to an individual’s background and experience in relation to his or her goals for the event. Just as with a traditional training plan, he likes to work backwards from the event, factoring in time for a base phase, a build phase, a taper, and so forth.

Should you polarize your training?

Research suggests that the polarized approach—with 80% of your training being easy and 20% being high-intensity work—can stimulate greater training effects than the sweet spot approach even at the low weekly volumes we’re discussing. [1] Still, it’s worth modifying the approach when you’re targeting ultra events.

“I will argue that if your weekly training volume is six hours or less per week, you should focus less on the 80/20 distribution and more on another key principle of polarized training: that high-intensity work should always be done sparingly,” Connor says. “There is a body of research showing that the benefits of high-intensity work are on a bell-shaped curve.”

Two high intensity sessions per week is at the peak of the curve, producing the biggest gains, according to the data. Three sessions produce similar gains, but four cross over the curve into fewer gains and a greater risk of overtraining, says Connor.

To reiterate what all of our experts have said, intervals should be a part of your ultra-endurance training, particularly for those with limited time. However, two sessions per week are likely all you need to reap the rewards of these sessions. More than that and you’re only doing unnecessary damage.

One big ride

In many ways, a two-hour ride is nothing like a six-hour ride. Physiologically, psychologically, and nutritionally, these two endurance efforts ask very different things of an athlete.

Therefore, as you approach your target event, there is a benefit to placing all your allotted training hours for a given week—assuming you are rigidly constrained to those six hours—into a single ride.

“There’s no way to replicate that type of endurance effort of a six-plus-hour ride on a two-hour ride, or even on consecutive days of two-hour rides,” Kohler says.

During this six-hour ride, it will be critical to refine your nutrition strategy and create good habits. According to Kohler, that six-hour mark is key—once you are able to hone your plan for that length of time, everything that comes after that should follow the same principles.

“If you understand the general principles of how much you need, what you need, how your body responds up into that six-hour range, you have the tools you need—it becomes about following the body in a more intuitive way,” Kohler says.

References

- Muñoz I, Seiler S, Bautista J, España J, Larumbe E, Esteve-Lanao J. Does Polarized Training Improve Performance in Recreational Runners? Int J Sport Physiol 2014;9:265–72. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2012-0350.